Last week I stood at Seamus Heaney’s grave in Bellaghy. In a week of grey skies, the evening sun had come out; but the forbidding tombstone, with its legend ‘walk on air against your better judgement’, was untouched by its rays, the gloom mirrored my mood.

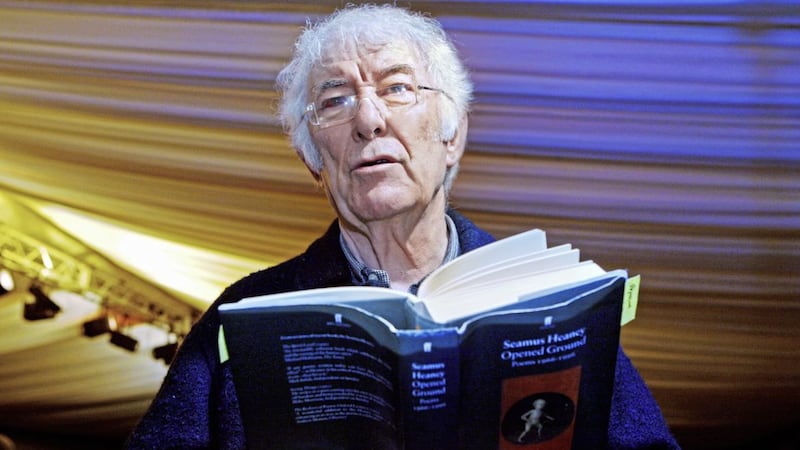

This coming Monday marks the eighth anniversary of Heaney’s untimely death. I did not know him well; but through work at Queen’s, his alma mater, and then Strathclyde in Glasgow, where he was receiving an honorary degree, I had the honour twice of having lunch with him.

He was everything you might imagine – good humoured, great company, and generous with his attention. My stock at Glasgow’s fabled Café Gandolfi rose when I brought him and his wife Marie in.

Even in non-literary circles Heaney had celebrity, but the tongue-in-cheek moniker ‘Famous Seamus’ was never so misplaced. He was as down to earth as they come.

I say I didn’t know him well. But, like many reading this column, Heaney was part of our lives. In a way, I grew up with him – introduced to him by an English teacher.

On a bleak winter’s day in 1972, I remember our teacher reading his poems to us. It was the day after Bloody Sunday, and they seemed appropriate to the moment. Our class was cut short and we were sent home early.

It was an unexpected mid-term break. Those days were too grim even for learning.

In our early teens, the storytelling was the poetry’s attraction; it tapped into a way of living that was not far from our own experience – even townies like me. We too had tasted the “summer’s blood” of the first blackberry, carried our cache home in buckets, and seen them turn fetid.

Heaney’s poems also helped us negotiate the changing relationships with those close to us as we became adults; for us boys in particular, how to relate to our fathers. Digging and Follower are extraordinarily powerful.

You did not need to be a nascent Nobel laureate to be able to relate to the image which opens Digging. “Between my finger and my thumb/The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.”

The opening up of grammar school education in the fifties and sixties took tens of thousands of us away from manual labour and into white collar jobs, pushing pens.

Although more stellar, Heaney’s journey from Toner’s Bog to the Swedish Academy, via chairs at Oxford and Harvard, was our journey too, especially those of us brought up as second-class citizens in the north of Ireland.

When I looked last week at the images of his family at the Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, I saw my own staring back at me: proud parents, desperate to give us chances they never had; siblings and cousins in cracked black and white prints outside my granny’s two-up two-down; my Limerick granny sending us with potato peelings for neighbour Aggie Barrett’s chickens; my gracious aunt May in the Bleary; uncle Hughie, Lurgan’s last tinsmith, who lived in the country and had an orchard full of apples and plums, and hedgerows thick with blackberries and sloes.

I’m not naïve enough to think we can go back to those days, before the troubles got into their stride, when there was the possibility of real social, political and cultural change. But it is clear from what Heaney said and wrote that he believed there was another way to bring this island back together again.

For a sense of that, it is worth reading his Nobel lecture, published by The Gallery Press as ‘Crediting Poetry’. It’s a wide-ranging defence of poetry’s “power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values”.

In the lecture Heaney talks about the chilling brutality of the Kingsmill massacre, and the final act of humanity of one of the Protestant victims who reached out to a Catholic co-worker, fearing the Catholic man was the intended victim.

I can put it no better than Heaney in that lecture: “The birth of the future we desire is surely in the contraction which that terrified Catholic felt on the roadside when another hand gripped his hand, not in the gunfire that followed, so absolute and so desolate.”

Ireland has been gifted with an abundance of poets – of all faiths and none - digging with their pens; as we contemplate our future on this island, we would do well to listen to them; to take our neighbours by the hand, and reassure each other that we are here for one another.