As unionists grapple with the Irish Sea border in the courts and on the docksides, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that once again unionism is in crisis.

Of course, that’s nothing new. Unionism has been that way since August 1968, when the first civil rights march from Coalisland to Dungannon challenged the culture and content of unionist rule.

In the intervening 53 years, unionism has lurched from one crisis to another, each one reducing its political weight, so that it now resembles a melting Arctic iceberg drifting slowly south.

So how has unionism got itself into continual calamity, can it ever become a progressive political force or will it continue to melt away? As often in this country, the answers lie in the past.

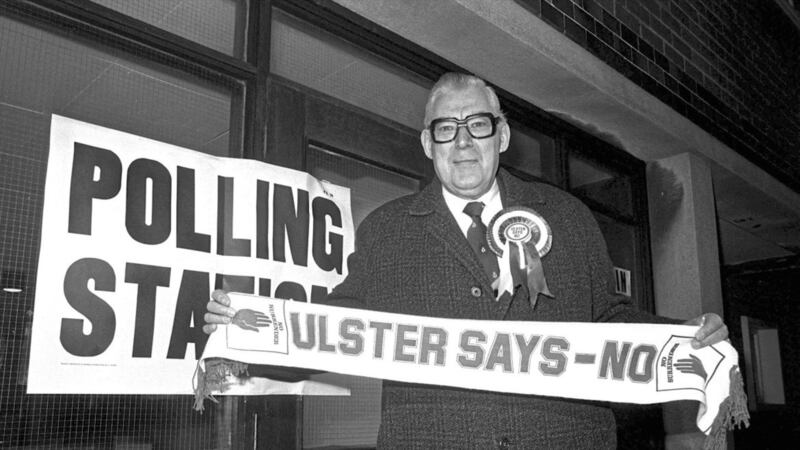

The most significant factor in modern unionism’s decline was the influence of Ian Paisley. His unionism was a prolonged bout of self-centred career progression, in which he opposed everything except his own appointment as first minister.

Employing the language of the Protestant Reformation, he infused his concept of religious salvation into the bigotry of his politics. It was a system which suppressed talent in what was his personal political party and promoted Paisley-type clones.

Only the uncompromising could be saved, except for him, who was the only person allowed to break his own rules. No one has since shown the leadership to ditch the DUP’s Paisleyism and bring unionism into the modern world. Peter Robinson did not have the inclination. Arlene Foster does not have the ability.

By imprisoning the DUP within its own inflexibility, Paisley set the agenda for wider unionism, which dared not deviate from his “not an inch” mantra. With no tradition of political debate nor a coherent body of political thought, Paisley’s unionism became intransigent, inward-looking and ultimately politically insolvent in a changing world.

Promoting union with Britain, rather than arguing for amalgamation into Britain, showed an Irishness which unionism has failed to admit and which nationalism suppressed in the Good Friday Agreement.

Today unionism displays no significant understanding of publicity or politics. When nationalists were knocking down polystyrene walls in south Armagh to symbolise opposition to a hard border, unionists did nothing. They did not realise that the EU would play the green card or that Boris Johnson would keep the Orange card in his pocket.

In terms of publicity, unionists fail to use the obvious reply to nationalist jibes about supporting Brexit. They might politely point out that they merely support what was Sinn Féin policy until a few years ago and retort that they admit to being principled, unlike SF which did a U-turn over the EU. They appear unable to say that.

Now, faced with the Irish Sea border, they are like the Danes at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, with the sea at their back and the setting sun in their eyes. But that predicament risks allowing loyalist paramilitaries a greater influence over the nature and direction of unionism.

Their loyalty to God and Ulster has been corrupted by their involvement in drugs (for cocaine and Ulster?) and they are heavily penetrated by British agents. But they must not be given a cause to fight for.

Despite unionism’s crisis, the most popular politician in Stormont today is health minister Robin Swann. A unionist and an Orangeman, he is better known as a decent human being, who has relegated his politics behind his desire to serve everyone here, Protestant and Catholic alike. He is a one man People before Politics Party and therein lies the future for unionism (and indeed for all future politics and society here).

Swann’s constitutional beliefs do not define his behaviour in government, a stance which would be a useful pre-condition for appointing all future executive ministers. The popularity of his non-sectarian ministerial behaviour clearly suggests that for unionism to become a progressive political partner, it must dump Paisleyism and adopt Swann-ism.

Nationalism must give it the room to do that.