My children enjoy a very different life to my own and I enjoyed a very different life to that of my parents.

The reason for this generational change was not by an accident of birthright, but because of all those who came before us.

Those who worked to make our world better, often at the expense of their own personal and family life.

Politicians get a bad rap, and at times deservedly so.

But let us not forget that it is the bravery and action of politicians, who came from the communities they loved and represented, that made life better for the many.

John Hume towers above the careerist politicians who use it as a platform for self gain and self promotion.

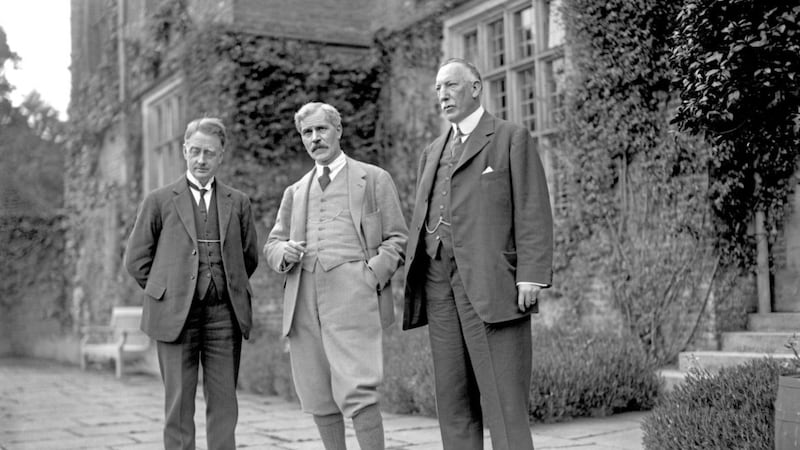

And when we look back at the generation of politicians, good or bad, that shaped Irish politics, one thing is true of them all.

They were activists who believed strongly in a cause, the term 'career politician' yet to be invented.

We've a tendency to eulogise the dead, to sanitise their bad points and emphasise the good.

But for John Hume his 'bad points' - stubbornness and single-minded determination - became his strengths.

Ian Paisley was best known for saying 'No', John Hume for never taking no for an answer.

A working class Derry lad, his love of history and interest in civil rights battles around the world inspired him and a small band of others who marched for equality.

As we remember him this week and his contribution to all our lives, let us not forget he started as a radical young civil rights protester on the streets of Derry.

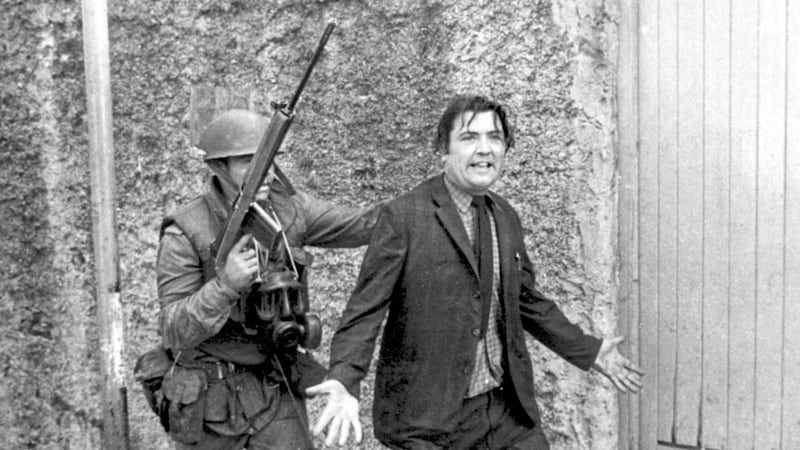

Pictures show the floppy haired Hume being pinned against a wall by a British soldier, or facing riot clad police in an act of defiant defence of his community.

He hated violence and the misery it brought to the families of the victims, he made his point through civil resistance modelled on the actions of people like Martin Luther King Jr.

Hume also knew that while there was inequality there would always be violence and so set about empowering his community.

When banks refused to help those on low incomes and loan sharks tried to exploit them, he founded the Credit Union, the lifeline to every working class family, regardless of religious beliefs.

Annual holidays, a family car, a Christmas without debt, a school blazer.

He knew how to work Irish America for the benefit of the economy and used his connections there and later in Europe to bring jobs and investment.

He knew that education was our pathway out of poverty and promoted it at every opportunity.

The Hume/Adams talks were so controversial that they remained secret for many years.

Once made public it was John Hume who bore the brunt of criticism for speaking to Gerry Adams while the IRA were still active.

Criticism that at times came from within the British establishment, who had their own clandestine talks process with republicans but who lambasted others for doing the same.

Torn to shreds by sections of the media who viewed my community as an underclass, to be battered into submission rather than talked to as equals.

Hume had a vision however, and he was not to be deterred from that even when it risked his own safety and took him away for lengthy periods from the family he adored.

At one stage in the process it was like all the world was against him and the easiest thing to do would have been to walk away but he, along with others, from within Sinn Féin, the Irish government and those with influence in the US, persisted.

The Good Friday Agreement is a testament to that perseverance.

Imperfect? Of course it is.

Part of a process rather than a settlement it was left in the hands of others to nurture with a mixed bag of results but the alternative was so much worse.

Those younger people who have only heard of Hume in his passing might be pondering what all the fuss is about.

For me it can be summed up in one terrible fortnight of violence, back in March 1988.

Gibraltar, Milltown Cemetery and then the corporals killings.

It was violence on such a scale that for me at that time it felt like the end of days, there seemed no way out.

Fr Alec Reid, who acted as a conduit and facilitator of the talks for many years, later spoke about how he attended the funeral of one of the Milltown victims to get a letter from Gerry Adams that was to be passed to John Hume.

I'm thankful he did, thankful to have survived those brutal times and thankful my own children never had to experience them.