A ‘DECADE of centenaries’ was an awful prospect. Now that we’re about midway through has it been so bad?

The darkest outlook would have brought ceaseless moaning this year from unsatisfied memorialists of both Somme and Rising.

There has for sure been nit-picking, scrapping about council-funding. Poor-spirited share-outs by unionist-controlled councils, true, but maybe radiating annoyed disappointment rather than heat.

Behind the quibbles a sense creeps out of some people in some places trying their best to think afresh about events of which they only ever inherited views, and fairly limited views at that.

Best of all is an impression of history making new sense, often in minds long ago convinced it was a boring business.

Which usually means people decide in school days that it is too complicated, hard, a subject for class swots, the born students, as if everyone couldn’t be interested, given the right materials in the right way.

It was nice to hear recently of a talk in Lisburn where the organisers put out 50 chairs and thought they’d be lucky if the room half-filled, then had to move to a bigger one.

But the speaker was historian and local man Philip Orr, said to speak almost as well as he writes.

Local history only ever hooks a few, an enchanted minority, partly pleased to stay the few, the select; sometimes responsible for scaring or boring away possible recruits.

There is more powerful magic when someone begins to realise that perhaps a not so distant relative of their own woke up on Easter Monday 1916, say, to hear rumours of trouble in Dublin, or got caught by chance in Dublin just as Pearse and company proclaimed a republic in a country already divided about being at war.

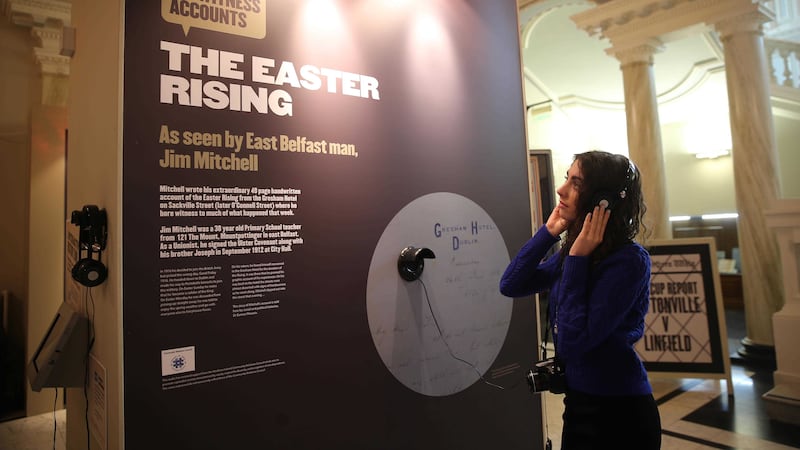

In the past week a decent attempt has begun in a Belfast City Hall exhibition space to show and tell a slice at least of 1916 in the round, the cranking up of passions from 1911-12 through the Great War, War of Independence, Partition, Civil War, the context of the Rising and Somme.

Such lists can deaden some ears, make people say they hate history. Personal stories rescue history by connecting people back to vivid experience.

In addition to lucid overviews, voiced and printed, the city hall show scores high for two accounts in particular: very different and told in opposite ways.

One is largely pictorial, with a dramatic enough text if mostly in officialese. A pair of photographs of 24-year-old Hugh Francis De Salle McNally show him in Irish Volunteers uniform, and in his Royal Navy greatcoat.

A ship’s surgeon, born and schooled in Belfast, (St Malachy’s, Queen’s) he died with British minister for war Lord Kitchener - and 650 others - when their ship sank off Scapa Flow, mined, or torpedoed by a U-boat.

A letter to his parents expresses sympathy from local worthies in the Volunteers, the best known Belfast nationalist councillor among them.

(Elsewhere the exhibition notes that soon after the Rising Belfast volunteers were deported, through Dublin, to prison in England.)

Another Belfast man left a witness account of the Rising, from an unusual viewpoint.

Jim Mitchell was a 38 year old primary school teacher who signed the Covenant in the City Hall in September 1912 with his brother.

In 1916 he drove to the capital, Dublin to enlist in the British Army, on his Easter holidays.

On Easter Monday they told him in Portobello Barracks not to join up straight away, to go off in the sun first and enjoy the Fairyhouse races.

He came back to find the Rising had begun, and was stuck for the duration in the Gresham Hotel (on what was then Sackville Street, at the far end from the General Post Office).

He ventured out a few times, and wrote, on 49 pages of hotel notepaper, what he saw and some at least of what he felt.

Historian Eamon Phoenix, whose selection from 1916’s Irish News run across the page from this, does an audio commentary on Mitchell’s story, adding that because his diary lay in a bank vault for decades he thought Mitchell hadn’t come back from the war.

Then he found he was still alive in 1920, in the house where he lived before war and Rising.

The exhibition is only the second in a ‘decade of centenaries’ series. Some no doubt would rather no exhibition than read and hear about Somme alongside Rising.

But context is all. If some think afresh afterwards, it will have done well.