In 1906, Cork native Tim McCarthy was as new to the job as the building he shared with a small staff of journalists and printers in the heart of the then booming-for-some city of Belfast.

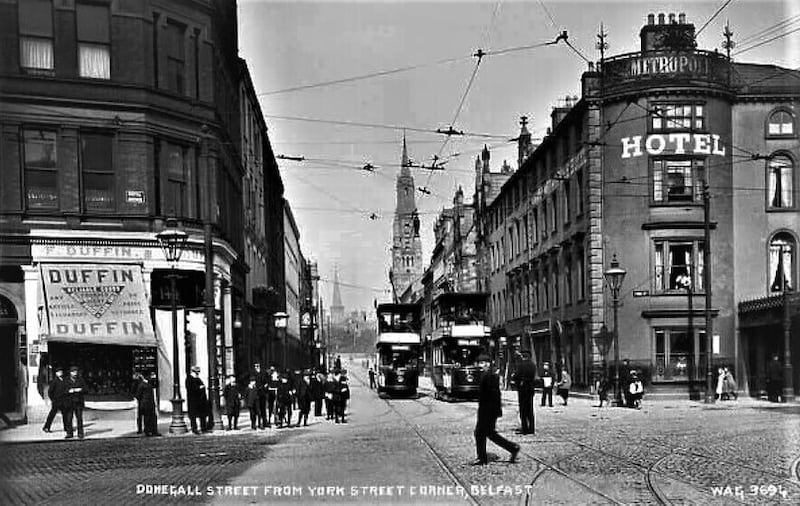

Outside the door of the extensively refurbished building housing The Irish News and Belfast Morning News, the tracks for the electric tram route had only recently been laid down.

Passengers on the north side of the city centre could jump on and take the ride down Royal Avenue to Donegall Square.

At the square’s centre was the grandiose, dome-topped, made from imported Portland Stone, Belfast City Hall, the just completed home to the unionist-dominated Belfast Corporation. It cost £390,000, more than £12m in today’s money.

Copies of the newspaper from the time reveal council proceedings were covered in incredible depth by The Irish News. Space was shared with columns and columns of foreign coverage, including many the previous year detailing a failed Russian expansionist war with Japan.

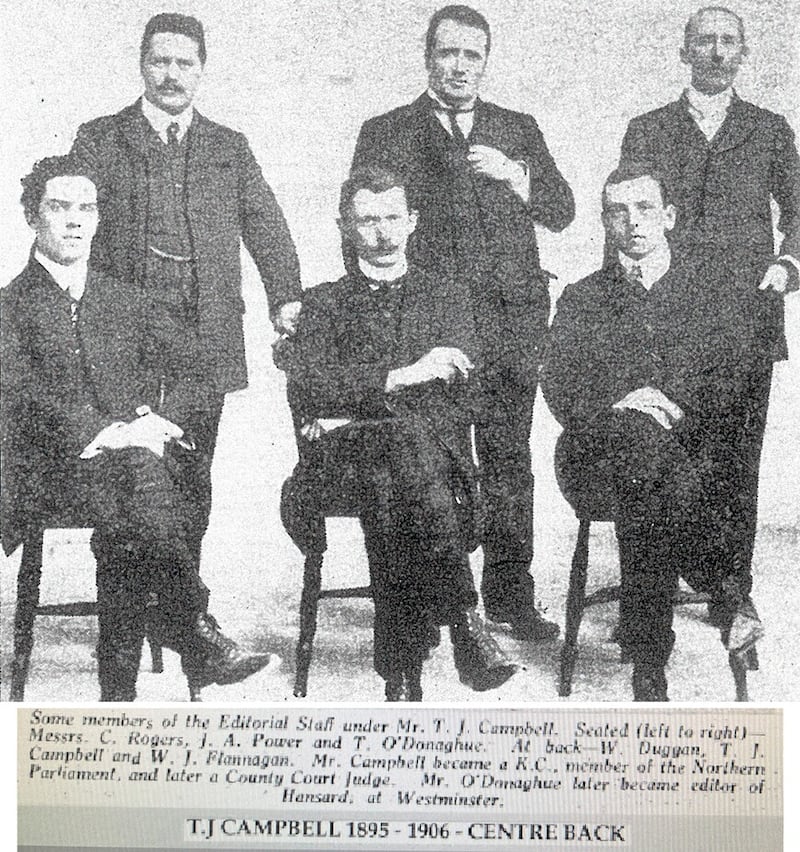

But McCarthy, installed that year as editor of The Irish News, already a seasoned editor at 38 and one time internee under the coercion acts of the late 19th and early 20th century, is likely to have left City Hall to one of his team of just seven reporters and sub-editors.

Another building on Donegall Square was his more likely destination, the preferred spot for the leaders of the nationalist, largely Catholic, population of the northern counties and the city. At the time it was estimated around a quarter of the approximately 400,000 population identified as Catholic.

As McCarthy stepped out of 113-117 – just doors down from the paper’s old home – he may have looked about him before setting off on the walk or tram ride down Royal Avenue to the Linenhall Hotel.

It was a bustling scene, the street north and south of the York Street/Royal Avenue junction home to a wide variety of businesses, printers, tailors, watch makers, cycle shops, also selling guns, business agents of all types, a smattering of solicitors’ offices – and a Turkish baths.

Across the road was McNeill’s Pub, later the Front Page, just a few doors up from The Arcade, a bar and billiard hall owned by the McGlades, itself only some steps away from The Temperance Hotel, the Belfast base of the Irish Temperance League.

A debt collector had moved into part of the old Irish News building, the rest vacant. At the corner with York Street was the Grand Metropole Hotel and Café, also owned by the McGlades. To the left down the street stood the first section of St Anne’s Cathedral, only recently finished, part of an overall job that would take 80 years to complete.

And it was by then Belfast’s Fleet Street as the Irish News shared the area with the Evening Telegraph around the corner, the News Letter and Belfast offices of the Irish Independent down the street. The Northern Whig building was a short distance away on Victoria Street. It hardly needs to be said The Irish News is the last to leave.

The Linen Hall Hotel, on Donegall Square East at the corner of Chichester Street, was owned by Patrick Dempsey, the recently appointed chairman of the Irish News. It was the epicentre of the northern nationalist Home Rule and land reform movement.

At its centre was Joseph Devlin MP, a key figure not only in the wider all-island nationalist movement but also for the Irish News over the next near three decades.

Devlin and his United Irish League, with strong support from the Ancient Order of Hibernians, had managed to win control of The Irish News by 1906, after nearly 10 years of trying.

The defeated were led by the Bishop of Down and Connor Henry Henry and the more “clerical” minded, in the ascendancy since the paper’s birth following the 1891 Parnellite split.

Those gathering at the Linen Hall meeting could hardly have imagined what would happen over the next 15 years and beyond. World War, the death of Home Rule, the War of Independence and Civil War and with partition, the shutters coming down on nationalists in the north.

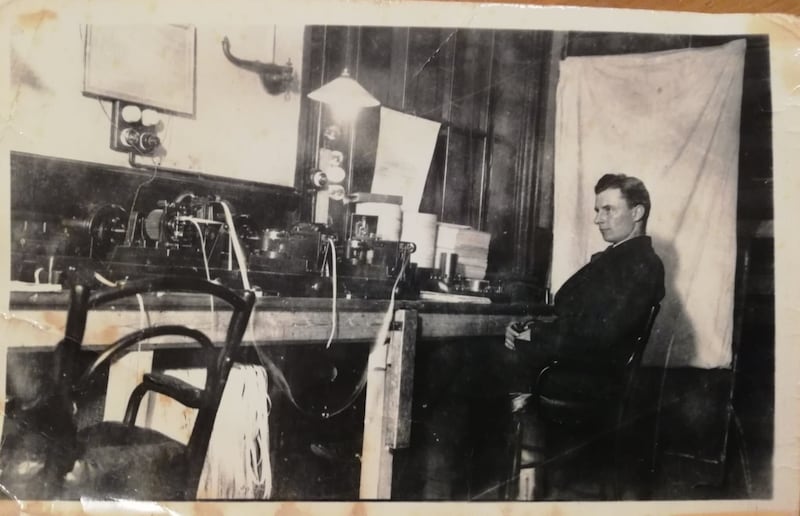

One of McCarthy's last hires two years before his death in 1928 was 32-year-old Kerry man Tim O’Connor, a Morse code telegraphist.

He began his career with Valentia Cable Wireless Station, went to sea during the First World War, spent time in London with the Press Association before making Belfast his home. He had married a Belfast woman, Frances Clerkin, later for many years a teacher at St Dominic's.

O'Connor, hired on £6 17s a week, around £540 today, worked for the company for nearly 40 years under the editorships of McCarthy, then for a short period Sidney Redwood and Robert Kirkwood.

Redwood was an Englishman so remembered for his drive that the legendary reporter and columnist James Kelly described working under him as being like a "galley slave". Kelly fled. But Redwood is credited with helping to right the ship with rising circulation and sounder finances.

He was followed by Kirkwood under the ownership of the McSparran family but with shareholders scattered across the island and beyond.

The later holders of those shares were tracked down and won over decades later as the recently deceased Jim Fitzpatrick took control of the paper in the early 1980s.

O'Connor's daughter, Brenda, remembers during the Blitz how her father remained in the city with the rest of the Irish News staff as people left for the country, including herself, her sister and mother. The Irish News was damaged during the German raids, not the last time it would be bombed.

The now 84-year-old also remembers how her father always enjoyed being one of the first in Belfast to know the sports results. He died in 1965, his funeral in Ligoniel attended by representatives of most of the city’s newspapers and five priests.

Later that same year his grandson was born in Argentina. But Pedro Donald ended up straying not too far from the tree. He is the owner of The Sunflower bar around the corner from the closing Irish News building.

Paddy Meehan was just 17 when he stepped through the doors of 113-117 as a junior advertising representative, excited to be working for the Irish News.

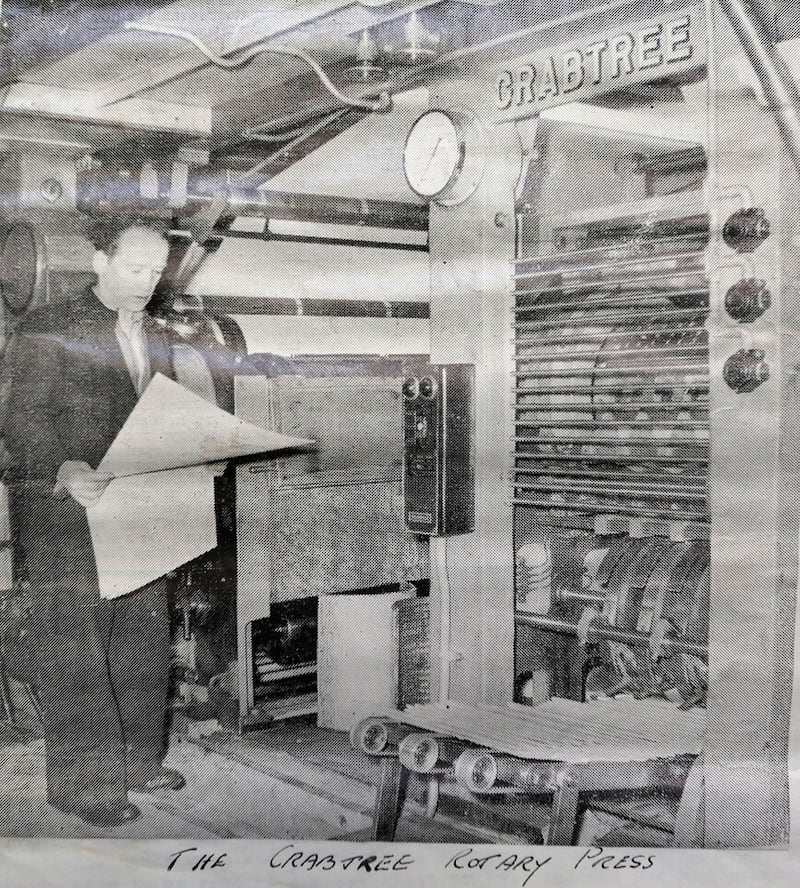

The linotype machines and printing presses covered much of the first floor. Vans lined up at the side of the building to deliver the paper, “off stone” at 2.30am.

Paddy remembers the headline on his first day: “Bomb ccare in Pakistan.”

“In big type, right across the front page, bet it went down a storm on Friendly Street,” jokes Paddy.

Less than a decade later, there began the regular scares much closer to home – and actual bombings.

The presses were down for three days early in 1972 after the Co-op building at the corner of York Street was destroyed. There were concerns vibrations from the machines could further collapse the structure, says Paddy.

Then in July, 1972, the Provisional IRA’s own Belfast blitz on Bloody Friday caused serious damage to the building as one of the 22 bombs planted across the city exploded at Eastwood’s Garage on the street. The Irish News was not printed the following day, the last time that happened.

For Paddy, what comes to mind from those days are the swarms of birds above City Hall escaping as far away as possible after the bombs went off. He remembers another time the body of a binman being shovelled up on Donegall Street.

Paddy, who worked for the paper for nearly 50 years before his partial retirement in 2006, does note the collapse of unionist control benefited the Irish News financially. For the first time, beginning in the 1970s, government advertising appeared in the paper.

His career spanned several editors, many staff and the takeover by Jim Fiitzpatrick in 1982, following which he says the paper was transformed.

For all, they were turbulent times to navigate, not too unlike more than a century ago.

Then McCarthy was at his desk inside 113-117 Donegall Street steering the paper through the early decades of the century as a strong voice for nationalists, anti-partitionist and firm advocate of non-violence.