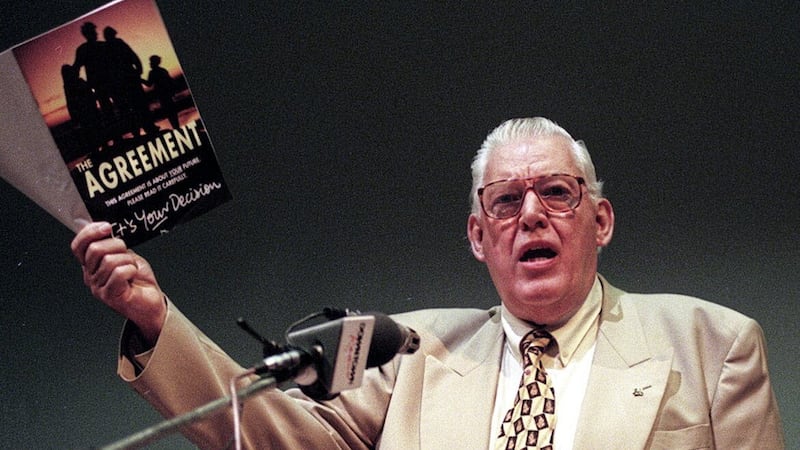

William Brown was introduced to Ian Paisley at a young age and for a short while was an associate of the political and religious firebrand. In his new book, he charts the career of the man he believes bears much of the responsibility for the outbreak of the Troubles.

::

LIKE Paisley I came from an Evangelical-Protestant background with a fundamentalist preacher father and a staunchly unionist mother. I therefore knew a lot about him while I was still a boy.

My first real encounter with the then up-and-coming young preacher Paisley was when my mother took me to hear his charismatic oratory at a rally of the National Union of Protestants in Belfast’s Wellington Hall – a frightening and enlightening experience. Later, when as a teenager I lived near him, I came to know him through my occasional attendances at his Free Presbyterian Church services.

This soon developed into a friendly relationship when he sometimes asked me to drive him on an undisclosed ‘urgent mission’ in my rickety old Austin Seven car. During one such adventure I first learned of his association with loyalist paramilitaries.

Indeed, it was not long before I came to see him as a man who was very much a law unto himself which, when combined with his deadly sectarian oratory, would eventually lead me to the conclusion that he was the most dangerous man in Northern Ireland and the one most responsible for the outbreak of our Troubles.

Those experiences provided some insights into his association with his legal mentor Desmond Boal, and with what was then known as the Maura Lyons affair – the abduction of a Belfast Catholic girl.

Because a few of my friends knew the missing Maura, Paisley and Boal assumed that I had knowledge of the case and asked what would I say if the police came after me. When I said I knew nothing and therefore would have nothing to say, Paisley referred to the biblical Rahab who ‘hid the spies’ and misled the Jericho authorities, suggesting that if I came to know something I should do likewise!

That and other episodes convinced me that the Paisley was full of contradictions, volatile inconsistency being one of his chief characteristics.

It was extraordinary that a professed follower of the Prince of Peace should agitate and inspire loyalist bombers in the years before the rise of the Provisional IRA – creating the sectarian strife that did so much to provoke that rising.

This was only one aspect of his contradictory inconsistency. He created his overtly sectarian Protestant Unionist political party in 1964 and shortly afterwards changed/reversed its name to the Democratic Unionist Party.

Like his politics, his religion was marked by conflicting principles. He claimed to be a Presbyterian, establishing his Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster in 1951 after causing a rift in the Crossgar Presbyterian Church, and yet he was never a Presbyterian.

Like his father who unconventionally ordained him, he was theologically always a Baptist. He used the name Presbyterian because he favored a centralized system of quasi-Presbyterian government to facilitate his control as perpetual Moderator rather than that of an independent Baptist system that practiced congregational self-government.

As an egotistical narcissist, Paisley was a stranger to that first among Presbyterian qualities – ‘consistency of character’. This was never evident in either his volatile politics or turbulent religion.

There are many examples of his ‘door banging in the wind’ shifting character. One which combined both his religion and his politics was his membership with the Orange Order. He had joined the Order in the 1940s because he thought its diverse politico-religious character could provide him with an effective network to service his growing interests and ambition. But things didn’t work out.

Paisley was a religious separatist who not only believed that that Catholic Church was apostate, but so too were the mainstream Protestant churches that had Orange clergy and were allegedly involved in what he called the Rome-ward trend. He therefore called on members of the Protestant churches to ‘come out from among them and to touch not the unclean thing’.

This inevitably led to a fall-out with those clergy he accused of apostacy and heresy, this resulting in his leaving the Order after many years, but he would later change his position on that when this accorded with his political ambition.

Paisley therefore was not marked by the Presbyterian quality of ‘consistency of character’ although sadly for most of his life he did display consistency in his negative and divisive sectarianism. But in the end even that would change with the damascene conversion I describe as his final volte-face.

His ambition to become the ‘top man’ was a major factor in that final chameleon change, and if for most of his life he behaved as an inconsistent charlatan there is reason to be happy that, in the words of Seamus Mallon, he finally tried to make amends for ‘the substantial damage he had done over many years’.

:: Ian Paisley as I Knew Him: Charismatic, Chameleon or Charlatan? by William Brown is published by Beyond the Pale Books, Belfast.