IT'S often easy to blame politicians for the failings in our politics – we had three years of no government, and just two years after resolving this, a leaderless executive following the resignation of the first minister.

Whilst politicians were responsible for taking these decisions, over 20 years later it is increasingly clear that the institutions created by the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement are struggling to accommodate a changing society and the expectations that people have of their elected representatives.

With the joint office of first minister (in spite of the 'deputy' title), enforced designation of MLAs as nationalist, unionist or other and a voting system in the assembly which places less value on the vote of 'other', can we be that surprised if accusations of a move from power sharing to shared out power are growing increasingly louder?

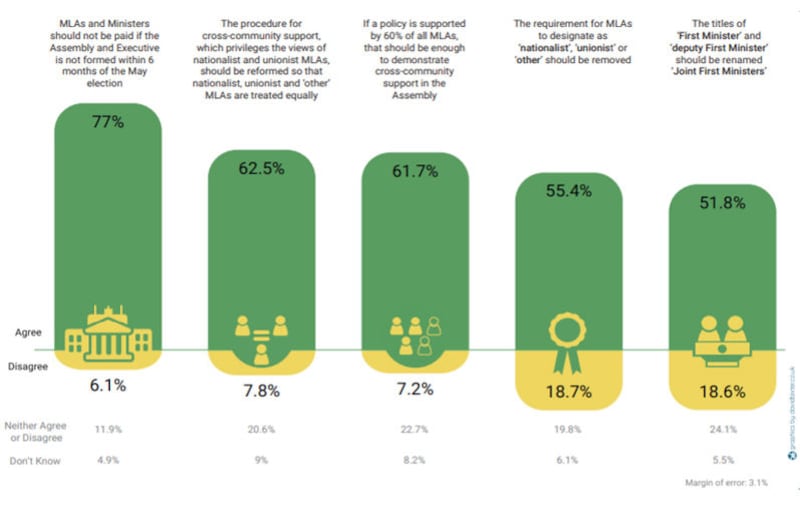

More than half of those surveyed for today's Institute of Irish Studies-University of Liverpool/The Irish News poll supported a removal of the requirement for community designation of MLAs, and more than 60 per cent agreed on the need to remove cross-community support mechanisms for voting in the assembly. This clearly shows an appetite for change, and for a move away from the two-tone identity approach that has defined our politics for so long.

Does that tell us we are more trusting of each other now than we were in 1998? That we can do away with the safeguards built into the system to protect rights and equality? It might seem like a stretch to suggest that we are ready for the 'happy ever after', but it does show a more nuanced understanding of evolving equality issues that aren't necessarily protected by the scaffolding of 1998.

This is reinforced across all community groups by the fact that the majority agreed that devolved politics works better when people don’t focus on the constitutional question. We might read this as further evidence that whilst the aspirations of whether our future be to remain within the UK or as part of a united Ireland, it is no longer all defining.

We need only look at the last few months of the assembly to see how productive it can be when it gets to work – in a matter of weeks, half of the 46 pieces of legislation passed in this mandate completed, which included important developments such as an opt-out organ donation system, protection from stalking, improved services and rights for people with autism and tackling climate change.

Whilst there might be said to be a generosity of spirit in the desire for reforms to the system in some of the poll results, there is very little appetite for another political crisis following the election in May.

This is not entirely surprising, given that it was only two years ago that our institutions were restored. However it is worth remembering that this isn’t unique to our system but is common in the formation of coalition governments across the world – indeed it was four months of negotiations before a government was formed in the south in 2020.

What is clear from the poll is that most people want a system that can deliver for them, and which gets on with the job of governing. And whilst the election may produce different results, politicians will continue to grapple with the same challenges of a system that sometimes works against them.

So if we are to give people the politics they want, an election alone won’t fix the problem. In the same way the health service won’t be fixed by tinkering at the edges, the political system needs an overhaul to give our politicians the best shot at delivering for the people they represent.

Despite being modified over the years, our devolved institutions can’t remain fundamentally frozen in time; both the electorate and those they elected are changing, so the institutions must now find a way to accommodate the new realities of a society that is perhaps more at peace with itself than we give it credit for.

:: Anna Mercer is deputy director of political consultancy firm Stratagem.