VICTIMS' campaigner Jude Whyte recalls his idyllic childhood in Belfast's Holyland before the the Troubles impacted deeply on the Lower Ormeau community.

:::::::::::

The Lower Ormeau Road was a strange place to grow up.

University Street in the 1960s had a weird, bohemian feel to it.

Next door to us at No 139 was a Lutheran church. I got my first job there in 1966, aged nine, a cleaner for Pastor Rose Marie Cobalt.

Two doors up was a homeopath called Mr Hamilton and beside him was our granny (no relation) who took in boarders from the boys' home in Kircubbin, Co Down.

At the back door was the Pepsi Cola company, a place where all the local kids got work as van boys as soon as they could walk.

It's hard to believe I was in Warrenpoint when I was seven, delivering lemonade to cafés and various business outlets.

Going out the front door and turning right we had the North Cricket Club, while if one turned left there was Queen's – the north's only university at the time.

It was all there to be explored, and of course a few 'windies' broken along the way, for Ireland, you understand.

The Holyland was then a working-class Protestant area, doorsteps covered in cardinal red polish, neat gardens with flag poles rarely empty, the obligatory bonfire every summer and a good dose of 'kick the pope' bands going up and down the road from March through to late October.

Our house was a happy house. Ten kids, buckets of family allowance. Mum and dad working, with talk of getting a motor car soon.

England winning the World Cup, Celtic the European Cup, while Down brought a trophy with a strange Protestant name over the border three times.

"Oh my", mum used to wonder, "What in God’s name is wrong with those turbulent rebels on the Falls Road?"

The first time I suspected something was... erm... not quite right was in 1968 when kicking a ball around Dudley Street at the corner of Fitzroy Avenue.

It lives in my mind as it was the day that some uppity Catholic, who clearly didn’t appreciate the wonderful entity of Northern Ireland, went into a house somewhere in far-off Tyrone or Armagh without permission. Such cheek. His name was Austin Currie.

Anyway, Mrs Edwards rang the cops and in time they arrived and lined us all up against the wall.

This rather corpulent fellow smelling of alcohol began by asking us all our names. Well, that was easy – Paul Whyte, Jim Whyte, Ann Whyte, Kevin Whyte.

He then came to the fifth and sixth members of this active service unit, looking menacing and in need of another drink I suspect.

He said to Jimmy: “I suppose you're another Whyte?”

Jimmy, being a solid law abiding son of Ulster, replied: “No, I am Green."

The cop then punched him in the face, before kicking him on the ground. His older sister screamed in terror while we all ran as fast as we could up the entry in Dudley Street to tell mum and dad.

Seeing a grown man kick a child is something that lives with me forever.

Jimmy Green was a friend of our family, a child of a mixed relationship and an adopted son of my parents He was telling the truth while shaking in fear, simply speaking his name.

Mum said we must have been cheeky, while dad went to the police station at Donegall Pass to lodge a complaint.

I've never forgotten that day on the Lower Ormeau Road and how it signalled the beginning of upheaval in my beautiful world of cricket, the Ormeau Park, Botanic Gardens, the hothouse, Queens and Belfast’s first Chinese restaurant on University Road.

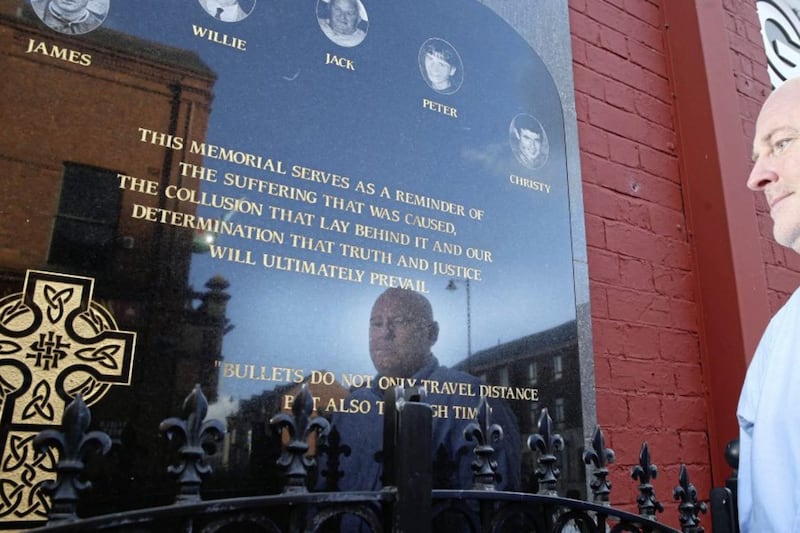

During what was known as the Troubles, 55 people were murdered in the Lower Ormeau, including five in the Sean Graham's bookies and six in the bombing of the Rose and Crown bar.

In an area of less than 2,000 people it remains the most abused yet proudest of communities.

I lived there until death came to my door with the murder of my mother – the same card-carrying member of the Alliance Party who could never understand what was wrong with those people on the Falls Road.

Alongside her died Constable Michael Dawson, a member of the RUC who came to her aid the night she was killed in April 1984.

The sight of Mark Sykes, shot five times in the same bookies’ massacre, being led away in handcuffs as he remembered his dead friends was a cruel reminder of how this community has been denied justice for 29 years.