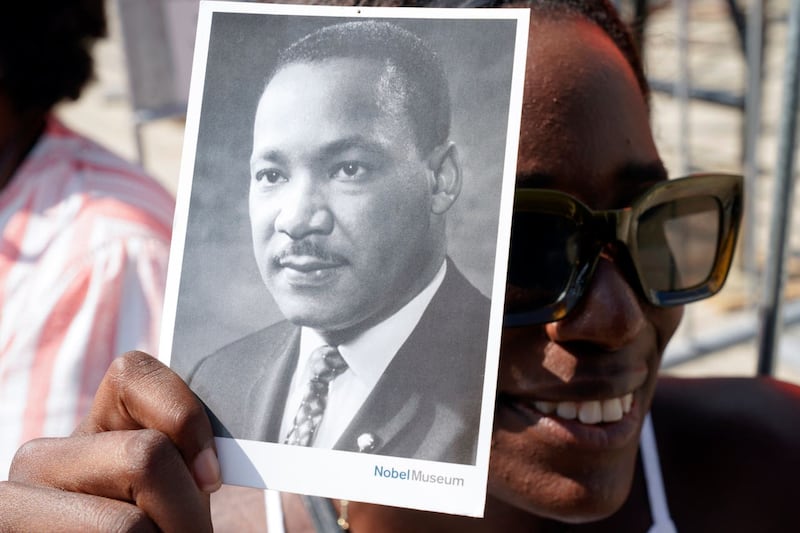

THE natural sadness of the news of John Hume's death has expressed itself in warm appreciation of his life of service, sacrifice, principle and vision.

So many people across public life have paid tribute to his singular contribution to achieving peace and agreement in terms that acknowledge previous differences.

It has also been edifying to read and hear from so many citizens who value John's tireless public endeavour, compassion and social ethic.

This giant of Irish politics who always looked to the 'big picture' is being fondly celebrated in all the shared cameos of "when I met John Hume" along with the grace or funny memories of small moments.

But all this deserved and heartfelt gratitude can still take for granted so much of what John did to keep building layers of understanding with such tenacity and steady focus when few others held any hope.

He had a read of history which imbued an analysis which drove his belief that better ways and better days could be achieved and the cycle of failure and violence could be broken.

That analysis challenged the political attitudes and assumptions of others but always affirmed the legitimacy of our different traditions and identities.

This might seem a truism now but, from a time before social media, I can remember the letters and phone calls castigating him for conferring legitimacy on the unionist tradition.

Unionists and Sinn Féin for years both dismissed his analysis that three sets of relationships had to be accommodated for an agreed solution to take hold.

Read more: John Hume's son to miss funeral due to Covid-19 restrictions

When the Hume-Adams talks became public knowledge in 1993, John Hume faced severe criticism for his dialogue with the Sinn Féin leader. In the midst of a media frenzy, he found an unlikely safe haven - San Jose pic.twitter.com/nGyfzpnoH7

— BBC News NI (@BBCNewsNI) August 5, 2020

He deemed that supposed solutions had failed or would fail by ignoring one or more of these relationships. That is why he vested far more significance than most to the formulation of the 'Three Strands' for the Brooke talks in 1991.

While those talks would not bring the prospect of ready agreement, they did confirm some acceptance by two unionist parties that dimensions they had previously resisted had to be addressed and the Irish government would be involved.

John had foreseen the pivotal potential of such a shift in unionist assumptions when he said that the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985 would lead a catharsis within unionism if that agreement held against mobilised objection.

Comparing it to the fate of Home Rule and Sunningdale, he noted that this could be the first time that sectarian solidarity might not succeed in vetoing arrangements that were both endorsed by the sovereign parliament of the UK and supported by the people of Ireland.

While waiting for that unionist catharsis, John Hume also recognised that both the fact and premise of the Anglo-Irish Agreement could be deployed to challenge anew the claimed rationale for 'physical force republicanism'.

Having been the first to advocate a "British-Irish framework" rather than focusing on just the "narrow ground of the north", worked towards it in the New Ireland Forum and persisted in spite of Thatcher's offensive "out... out... out!", he felt a personal responsibility to pursue that logic for peace when the opportunity for dialogue with Gerry Adams was confirmed.

For John, the Anglo-Irish Agreement was not an end in itself, not a crutch for the SDLP, but a new given that could enable reappraisal by those who were justifying violence and those who were rejecting partnership in government.

In his head, the Hume-Adams dialogue over so many years and the Brooke/Mayhew talks were not rival processes or separate bets as he was bringing the same analysis, principles and objectives to both.

There were days when I would leave him at Clonard or elsewhere to meet Gerry Adams and I would head to Stormont for the talks with other parties.

Part of the task was to ensure that no precepts were confirmed in either talks that would be incompatible.

He envisaged a convergence of the dialogue, where compatible layers of understanding from both channels, even if expressed differently, could inform an inclusive dialogue in the absence of violence.

He really was the pathfinder. He put his idea that any agreement from negotiations should be subject to referendum north and south to both Sinn Féin in the late '80s and unionist parties in 1991-92.

Neither accepted it then, but he stuck to the idea of recruiting and respecting the sense and source of legitimacy of both unionism and nationalism so that any agreement would be legitimate for both and its institutions could enjoy their shared allegiance.

His wise logic prevailed again and a double referendum was accepted in the ground rules for the negotiations that produced the Good Friday Agreement which was so powerfully mandated north and south.

It has been widely acknowledged that the blueprint for the Good Friday Agreement can be traced in John's arguments, articles, documents or speeches over the years.

While he stuck to clear principles with a laser-like logic, his capacity to listen could adjust language to reflect other considerations. He knew that successful dialogue is not just about mutual engagement but mutual adjustment.

For instance, he had asked for the Mayhew talks to try to agree on "realities and requirements" – ie the realities of the problem from all perspectives and consequent requirements of any solution.

He had no problem with the paper being called "themes and principles" to spare others from Humespeak.

He had huge resilience and his favourite quality attributed to him was his stickability.

This was tested many times, not least when he faced excoriation over the Hume-Adams dialogue. John and Pat were hurt by some of the vilification he was subjected to, given his persistent and strong record in opposing all violence.

He said that no-one's opinion of the IRA or its violence would change because he was talking to Gerry Adams. That definitely included his own. But he knew that people's opinion of him might be changed by this or reaction to it and that was a risk he would not resile from.

He and Pat sympathised with the genuine misgivings of those who had suffered from IRA violence. They were both anguished when IRA atrocities happened even while Sinn Féin were supposed to be talking to John about peace and inclusive dialogue.

It has been good to see the centrality of Pat's support for John's tireless, peerless efforts acknowledged in the tributes to John.

His family's sacrifice to allow the scale of his service and the distance he had to travel means that we owe them profound gratitude along with condolences.

We thank them for lending us John the peacemaker and John the changemaker. He was a changemaker even before politics and that ethic for social justice never waned as shown by his donation of his Nobel Peace Prize bursary.

The pathfinder knew where he wanted to bring us to even if we could not always see it as he took the community from divided grievance to shared governance.

Throughout that journey, he never forgot where he came from.

:: Mark Durkan succeeded John Hume as leader of the SDLP and is a former Deputy First Minister.

Read more: John Hume's son to miss funeral due to Covid-19 restrictions