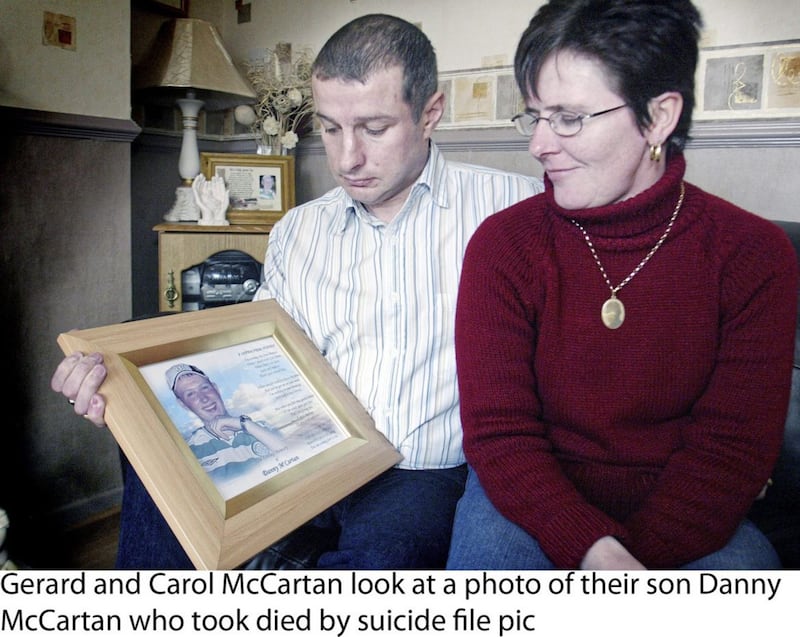

IT took eight years before Danny McCartan's teenage bedroom was touched by his parents following his death by suicide.

His last cigarette, the last song he played on his beloved decks and his favourite football shirt were kept intact as Gerard and Carol put their grief "on hold" in their search to get answers.

In the weeks after the tragedy in 2005, the unassuming north Belfast couple started asking questions about why specialist mental health services had failed their only son - who they believed would still be alive had the right help been in place.

Witty, outgoing, and obsessed with soccer and dance music, 18-year-old Danny McCartan began self-harming and smoking cannabis three years earlier after being bullied at school.

On April 11 2005, he took his own life hours after begging to be admitted to a psychiatric bed. He had previously been placed in an adult psychiatric unit due to a chronic shortage of places for teenagers.

Within a year of his death, British direct rule health minister and former Tory MP Shaun Woodward drove with his bodyguard into the nationalist working class Oldpark area and sat down at the couple's kitchen table to tell them he wanted to intervene.

At the time, Mr Woodward's visit was derided in some quarters as a PR stunt by the millionaire politician and former That's Life producer who had defected to Labour.

For the McCartans, however, his arrival was a watershed - leading to the first ever independent review of a teenage suicide in the north.

Completed in 2007, the confidential review delivered a scathing assessment of "seriously inadequate" Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in three former health trusts - that would be subsumed into the Belfast trust - and recommended an overhaul of the entire system.

Focus on mental health

- Links between suicide and paramilitary attacks needs addressed

- Finland: from suicide crisis to globe's 'happiest' country

It discovered appalling failings in Danny McCartan's "fragmented" care that led to him being "plugged and unplugged" from services in a way "not helpful to him or his family".

"From his admission in August 2004 to a psychiatric facility until his death nine months later, Danny had contact with three separate services - only one of which was set up to deal specifically with the problems of a young person and that was only for three months," the independent review team found.

"Professionals who were involved in his treatment did the best they could within the service in which they worked and the resources available to them but were working within faulty systems which failed in important respects."

The report's authors called for a "crisis service" for children and young people at risk of suicide and dedicated training for healthcare staff likely to come into contact with young people and their families seeking advice - an important element of the north's current suicide strategy.

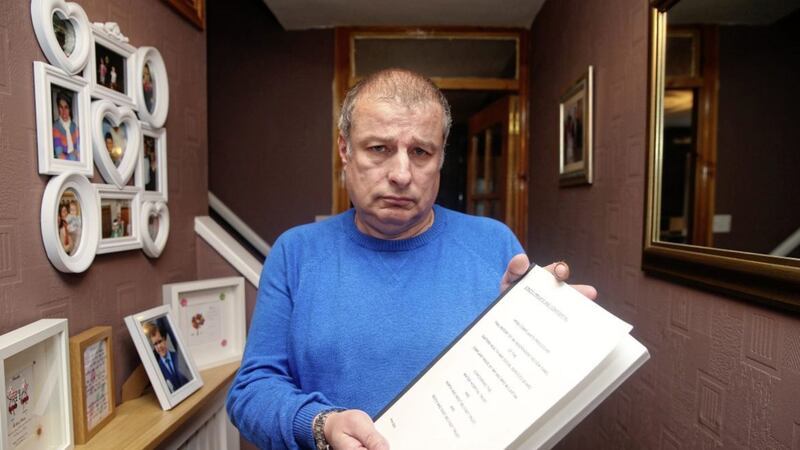

Sitting at the same kitchen table with a copy of the report, the gently spoken Mr McCartan said when he looks back to the events after his Danny's suicide, it's "like a dream".

It is the first time he has looked at the document in a decade.

"I couldn't understand then why someone would want to harm themselves, I understand now. It was 15 years ago, we needed information and there was none. We didn't have a computer, there was no Google. I didn't even have a mobile phone," he said.

Read More

- Spike in number of referrals to children's mental health services leaves hundreds on waiting lists

- 'Suicide is not someone with a mental illness, it's me, it's you'

"After Danny died I always used to carry round a letter in my pocket, thinking if I ever met the health minister, this is what I am going to say to him.

"We finally met Shaun Woodward at a suicide conference in 2006. I went to hand him the letter but he told me not to give to him and that he wanted to speak to us properly. A few weeks later he asked us to come to Hillsborough Castle. Afterwards he said, you have come to my house, now can I come to yours.

"When he visited, we had Danny's room exactly the way he had it the day he left this house and took his life. Mr Woodward went into his room and told us in there that he was going to order an inquiry - something he said he previously couldn't do.

"The minister was very personable, I liked him. It was extraordinary for us that a British direct rule minister was coming out here and doing this for us."

Following the review's release, the former head of the Belfast health trust, William McKee also visited the McCartans in their home and gave them a verbal and written apology.

The couple asked to sit on a group to oversee the implementation of its recommendations, which included training for staff "at all levels" who were exposed to teenagers and families seeking mental health support.

While they were initially part of monthly meetings with the former eastern health board, Mr McCartan said the report got "sort of lost" after a few years when a new 'super' Health and Social Care Board was created.

"Sometimes I look back and think - did this really happen? When it first came out, there was all the apologies. I always waited and wondered about what happened - but never heard anything back.

"Reading the report again, one of the things that jumped out for me was that 'all healthcare staff' should be trained in suicide awareness - have they all been trained?

"I also realise now that it put our grieving on hold. We couldn't really grieve as were so focussed on getting the report done and being part of the first 'Protect Life' suicide strategy."

One of the major developments linked to the review - the couple refer to it as 'Danny's report' as they "did it for him" - was the opening of a new child and adolescent mental health inpatient unit in 2010 known as 'Beechcroft' in south Belfast.

"After the report came out they built the children's unit and invited me and Carol up. When they opened, officials asked us if they could name part of it after Danny, but at that time we felt so many other people lost loved ones to suicide and helped us, that is wasn't appropriate," he said.

A former butcher, the 54-year-old Mr McCartan went on to become a high-profile campaigner for suicide awareness and prevention and came up with the initiative for the 'Card Before You Leave', whereby suicidal patients attending A&E departments are given a card upon their discharge, referring them for a mental health follow-up appointment.

He said he is "not ashamed" to admit he sought professional support to help him cope with his grief.

"I cried when Danny died but it wasn't until the report was finished and everybody went away, I just broke down crying. I needed to get help for myself.

"I was never angry with Danny. I always believed that Danny was failed as he had an illness and wasn't treated properly. The report even notes there were question marks around the drug he was given and its side effects.

"Danny was a great kid."

As the McCartan family immersed themselves in campaigning work, they were hit with the devastating news five years ago that their only daughter Caroline (35) has a rare genetic condition that has left her wheelchair bound and unable to speak.

Caroline McCartan has a 10-year-old son, Tiernan, who they say is the "joy" in their lives.

Tiernan stays in Danny's room during sleepovers at his grandparents.

"We kept the room exactly the way it was until eight years ago. We'll never forget Danny but we knew it was time," Mr McCartan said.

"There was tears in my eyes stripping the wallpaper and taking stuff out. There's lots of stuff we've kept.

"Because of Caroline illness, I had to pull back from suicide awareness group - I want to see people getting the help they need."

Before we leave, Carol McCartan comes in to say goodbye. She had been sitting with Caroline in the next room who had just been discharged from hospital.

She recollects the night her son died, saying she knew it had happened before she was told.

"I was working in a shop and heard the helicopters out. But I already knew he was gone, I felt it.

"We're living across the road from Sacred Heart Chapel and there's too many funerals for suicide. They need to do something."

Statistics about suicide

- The World Health Organisation estimates that 788,000 people died by suicide globally in 2015

- Suicide rates in Northern Ireland remain the highest in the UK - with men and women almost twice as likely to take their own lives compared with those in England

- Records on the number of registered suicides in the north began in 1970, when 73 people died. The most up to date figures relate to 2018, when 307 deaths were recorded. A decade ago, the were 313 deaths.

- Highest rates are among men aged 25 to 20 and women aged 40 to 49

- Recording criteria in England, Wales and Scotland changed last year to bring them into line with Northern Ireland - the rates went up accordingly in England and Scotland

- Three times as many people die by suicide in Northern Ireland each year than are killed in road traffic collisions, with 28 suicides per 100,000 men

- More than 70 per cent of people who die by suicide are not known to mental health services

- In the Republic, the suicide rate has fallen to its lowest level this century, although the recording of their statistics is different to the north. There were 352 suicides in the Republic in 2018 - 282 male and 70 female - or 7.2 per 100,000 of population

- Co Monaghan and Co Cavan had the highest rates between 2016 and 2018 while the Republic's lowest suicide rates were in Dublin

- Experts say the recession and austerity measures in the Republic led to an extra 476 more male suicides between 2008 and 2012. There were 554 deaths in 2011. The 'Connecting for Life' suicide prevention strategy was introduced in 2015. A previous strategy was introduced in 2005

Helplines

Lifeline is a Northern Ireland crisis response helpline service for people experiencing distress or despair. People living in Northern Ireland can call Lifeline on 0808 808 8000. Deaf and hard-of-hearing textphone users can call Lifeline on 18001 0808 808 8000.

The charity Pips delivers suicide prevention and bereavement support services, counselling and therapies throughout Northern Ireland. It can be reached on 028 9080 5850 or 0800 088 6042.

Samaritans provides a listening service if you need to talk about what you're going through. The number is 116 123.

The Irish News two-day special feature on mental health will continue tomorrow