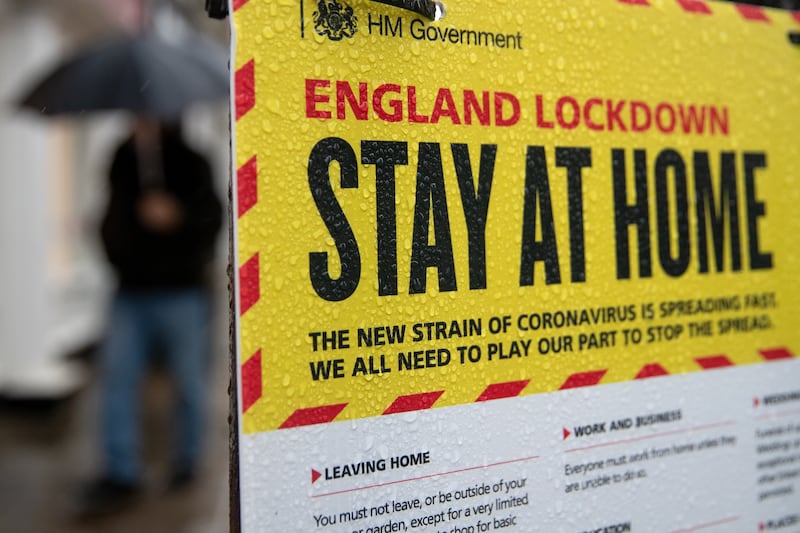

ONE of the stark impacts of the coronavirus lockdown has been on the formal qualifications system in education, writes Jim Clarke

::::

THE decision to award grades based on teacher assessments supported by existing evidence of achievement and statistical modelling has caused reactions ranging from relief to consternation.

I understand the concerns. From my experience as the first chief examiner of GCSE English and part of the design team for the qualification I believe the process is robust.

Central to the confidence level for this summer is the amount of externally validated data held by schools which entered students for CCEA examinations.

CCEA retained AS-levels as a component of the overall A-level grade and kept coursework and modules as part of GCSE and A-levels.

This gives our schools an advantage in terms of evidence and also in competence to assess student performance more accurately.

The challenges will emerge for the next cohort due to take examinations in 2021 for numerous reasons.

Course content for many subjects may have to be amended and the closure of schools has inhibited the capacity to gather evidence to help make assessments.

If there is further constraint or disruption to learning, there will need to be creative solutions.

While this may present as catastrophic, I believe that the experience this summer and competence of teachers can provide accurate and evidentially supported assessments.

The key is to ensure robust external moderation procedures to validate school assessments.

There have been many regional, national and international reports by bodies including OECD, the CBI, and Demos that questioned the validity of our qualifications regimes; not least for perpetuating the (sometimes false) distinctions between the `academic' and `vocational'.

Qualifications have been traditionally dominated by the `pencil and paper' methodology which by its nature is best suited to examining knowledge.

If we consider, however, that employers are demanding skills, attitudes and practical competencies which are transferable to the workplace then the school based emphasis on knowledge, because it is more easily tested, comes under question.

Education should reflect the overall ambitions of the Programme for Government (PFG) which should emphasise its interdependence with the economy, communities, health and justice. It must reflect the curriculum on offer.

There is an acknowledged need for a revised curriculum which should reflect the reality that skills are in demand in high achieving and successful economies.

There is a place for `hard' skills but the most flexible and transferable are the `soft' or `employability' skills. These include problem-solving; team working; critical/analytical thinking; creativity and innovation.

These cannot be tested effectively through pencil and paper. We need to create learning contexts in which these and core skills of literacy, numeracy and digital technologies can be developed then assessed.

In schools, this requires teacher assessments for formal qualifications because the learning of these skills can only occur through structured tasks, personal or group projects, simulations and problem solving exercises.

Formal qualifications must be robust, credible, comparable and equivalent to recognised standards.

My experience as a chief examiner and observations throughout my career convince me that teachers are very good at assessing pupils through a range of tasks.

The quality assurance measures to give professional and public confidence to teacher assessment are well tested, mainly through the evaluation of practical areas of learning. These procedures are through independent external moderation.

In law and medicine, the concept of cross-moderation of lecturer/trainer judgements with comparison of marking to reach valid and accepted outcomes is commonplace.

This was a feature across all subjects in the CSE system where scripts were marked internally by the class teacher then, if there was more than one class, there was an internal process to compare the marking and create a school rank order for each subject.

Thereafter there was an `area moderation' where several schools came together to follow a similar process.

Finally there was an examining board process where scripts were analysed and, if necessary, changes made to rank orders before grade boundaries were finalised.

This process had the added advantage of being a very effective staff development tool, particularly with respect to informing standards.

If Northern Ireland can alter how we award qualifications it will lay the foundations for a more equitable, inclusive and productive economy and society.

Covid-19 propelled us to find different ways to produce qualifications outcomes. The solution was to recognise the primacy of the teacher as a professional.

That should not be forgotten and we should not go back to the old regime but rather should carry out a broad review of the curriculum to reflect the connectivity of education to the broader strands of a PFG focussed on restructuring towards a system suited to assessing the skills, knowledge, attitudes and attributes necessary for young people to become beneficiaries from an equitable society supported by a high waged economy.

:: Jim Clarke is a former principal and chief executive of the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools.