NEWSPAPER reports indicate that Theresa May is ready to scrap the 20-year ban on grammar schools.

Creating more grammar schools will aid, social mobility, a government source said - "if you are a really bright kid you should have the opportunity to excel as far as your talents take you".

But as Rebecca Allen, an economist and director of the Education Data Lab research group said: "Grammar schools could be fantastic for social mobility if any poor kids went to them."

The chief inspector of schools in England, Sir Michael Wilshaw, spoke for many when he said: "Grammar schools are stuffed full of middle-class kids, a tiny percentage are on free school meals: three per cent. Anyone who thinks grammar schools are going to increase social mobility needs to look at these figures."

That grammar schools get excellent results is not the issue, the real problem is that the children who attend grammar schools overwhelmingly come from wealthy middle class families.

The situation is slightly better in Northern Ireland where 7.4 per cent of grammar school kids are on free school meals. That is still far lower than the 19 per cent of all post-primary children entitled to them, and the 28 per cent who take them in non-grammar schools.

In Northern Ireland 42 per cent of post-primary children attend a grammar school and the vast majority are from middle-class backgrounds. Where you have an education system that is based on `choice' the middle-classes who know how the system works and who have been through it themselves get first pick while the less well off get what’s left.

In the words of the educational researcher Diane Reay: "One consequence of a choice based system is that the working classes have largely ended up with the `choices' that the middle- classes do not want to make." Grammar schools do not cream off the best, they cream off the best placed.

It is now acknowledged that there were mistakes when the old system of grammars were being dismantled in England in the sixties and seventies and safeguards were not put in place to make sure children from poor families got a fair chance. In the new comprehensive system, academic selection was eventually replaced by house price selection. Research by the Sutton Trust in 2013 showed that the top 500 comprehensives based on scores on the English Baccalaureate had on average 7.2 per cent of their pupils on the free school meals register.

Of course everybody knows a poor working-class kid who went to a grammar school and as a result made a great success of their life. It's a bit like the old uncle we all know who smoked 60 cigarettes a day and lived to be 90. While these people undoubtedly exist they are outliers and nowhere else apart from education can you make policy based on the exception rather than the rule.

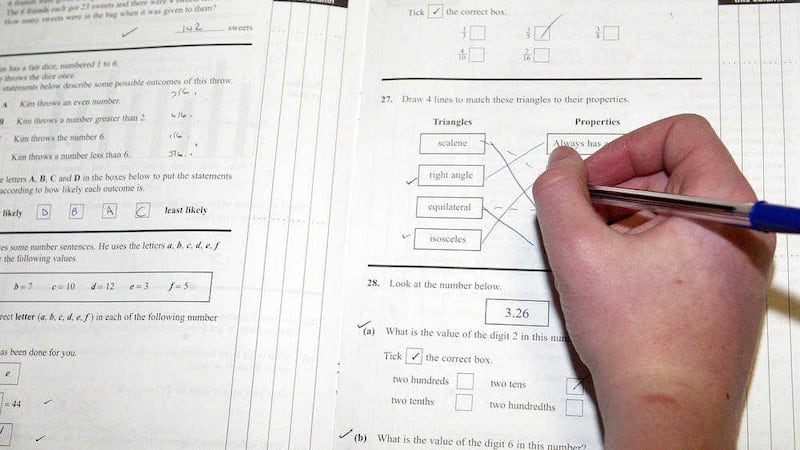

For every working-class child who passes the 11-plus, there are too many who either don't sit the exam or fail it. And, as business man and 11-plus failure Peter Prior who is leading a campaign against the opening of a new satellite grammar school in the borough of Windsor and Maidenhead has said: "I have never found that children do better because you tell them they are failures."

The idea that grammar schools were a huge driver of social mobility after the war is a myth. The vast majority of working-class people who achieved social and economic mobility in the decades after the war did it without the benefit of a grammar school education. It was a measure of the times, huge state expansion and economic growth fuelled by full employment. Put simply there was much more room at the top.

The non selective principle now governs some of the most successful education systems in the world from Shanghai to Finland.

If we are really serious about narrowing the class based attainment gap we need to be demanding more early years help for children from poor families and begin to phase out grammar schools and move to a genuinely comprehensive system promoting the good local school over supposed choice.

:: Jim Curran is a retired teacher and educationalist