SEÁN Quinn doesn’t go to Mass any more.

The reason, he says, is simple.

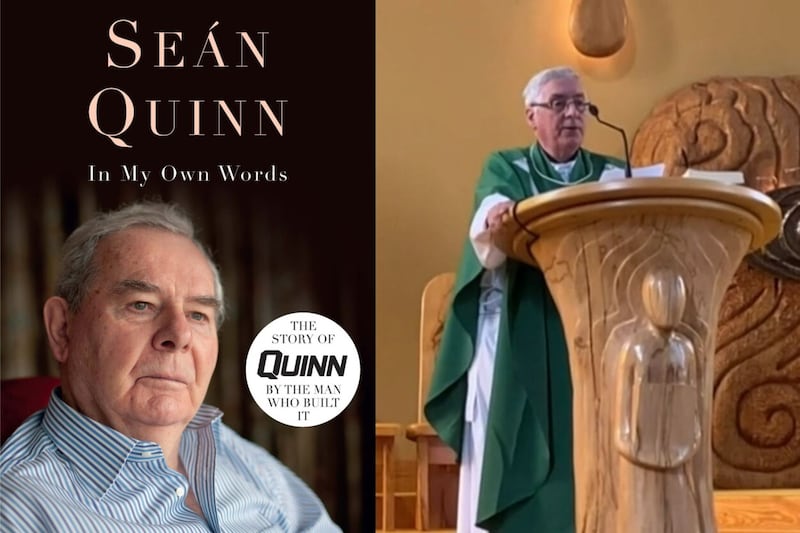

Two weeks after the brutal abduction and torture of Kevin Lunney near his Co Fermanagh home in September 2019, the local parish priest addressed the congregation in Sunday Mass at Mr Quinn’s church, Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Ballyconnell.

“This senseless atrocity follows years of threats, abuse, lies, and various forms of violent intimidation against the directors of Quinn Industrial Holdings (QIH),” Fr Oliver O’Reilly said, standing in front of a carved wooden pulpit.

“There has been a Mafia-style group with its own ‘Godfather’ operating in our region for some time.” Behind it is a “powerful paymaster and his criminal gang.”

Even though Mr Quinn wasn’t at church this particular Sunday and his name wasn’t mentioned during the sermon, he was incandescent with rage.

He visited the priest to tell him he had “no hand, act, or part” in what had happened to Mr Lunney, who was seized from his car by masked men, savagely beaten in a horsebox and left on a roadside in Co Cavan.

Read More:

Mannok: Timeline of violence, harassment and intimidation

A father of six children, Mr Lunney’s attackers broke his leg, sliced his fingernails down to the quick, slashed his face and carved 'QIH' on his chest. He was even doused in bleach.

The abduction threw a spotlight on a grisly border area grudge which had been going on for years and shone a light on the continued influence of paramilitaries in the border area.

Mr Quinn has repeatedly condemned the attacks on QIH executives and said that he and his family have no involvement with them.

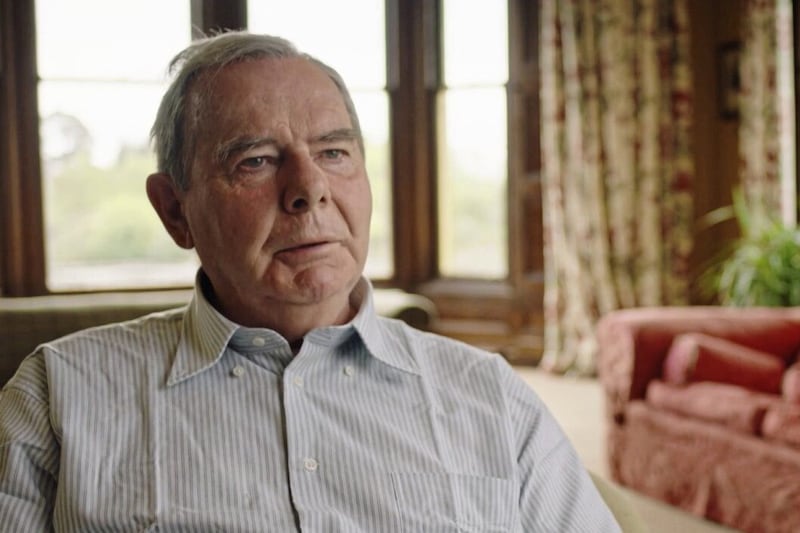

More than two years after the kidnapping, Mr Quinn has invited the Irish News into his home in Ballyconnell “to give a different narrative and an alternative view.”

It is the week before the verdict is due to be handed down to four men charged over the assault and false imprisonment of Mr Lunney.

The cast iron gates open onto a winding, tree lined driveway which leads to the grand Quinn residence. The stand out feature is the view from the back of the house of one of the local lakes, which also adjoins to part of the Slieve Russell Hotel’s golf course.

The luxury Slieve Russell Hotel, was once part of Mr Quinn’s huge empire - before it all imploded after a spectacularly bad bet on Anglo Irish Bank shares cost him €3.2 billion. He would, in 2012, be declared bankrupt and would later spend nine weeks in prison for contempt of court.

Mr Quinn quickly finishes off his bowl of porridge, not expecting this journalist to be so punctual. His wife Patricia provides a warm welcome with a cup of coffee and a plate of biscuits.

The last “ten to twelve years” have been “tough,” Mr Quinn says after some small talk about the COP26 summit and how if he still had control of his manufacturing businesses he’d have Artificial Intelligence (AI) in every factory.

He says that for a long time he harboured ambitions to oust the incumbent directors of his former business and win his company back.

But he is 75 now and “slowing up”. He doesn’t have the energy and he says his children, to varying degrees, all just want to move on.

“The kids want to get on with their lives. When we got into trouble 12 years ago we’d no grandkids. Now we’ve 13. They [my kids] say, ‘do you want to continue arguing for the next 10 years on ABDC?’ I said no, I will take this on. I’ll do the talking.”

Mr Quinn enjoys his Tuesday night card game with friends in Derrylin, where they put the world to rights. He also likes to drop into his local pub once or twice a week. He and Patricia enjoy a meal out.

It appears a quiet life but scratch beneath the surface and it is far from it. Mr Quinn is still extremely bitter about the buyout of the conglomerate he built from scratch.

He provides pages upon pages of well pawed documents - painstakingly gone through with a highlighter - which he feels prove his argument that he was wronged.

The Quinn companies were established in the pre-crash years by Mr Quinn, a farmer’s son who opened a quarry in 1973 with £100 and became Ireland’s richest man.

In 2007, before the global economic shock, Forbes said he was worth $4.5bn.

Quinn Industrial Holdings (QIH) was acquired from an insolvency process in 2014 by American private equity funds Contrarian Capital, Brigade Capital and Silver Point and local managers — including Mr Lunney, who worked closely with Mr Quinn before the business went into liquidation.

The bit that really sticks in Mr Quinn’s throat, he says, was the “breakup of the manufacturing business”. The ultimate betrayal, in Quinn’s eyes, was the sale of the glass business to a Spanish conglomerate before he felt he had a realistic chance to mount his own bid.

The Spanish company poised to sign a €400m deal offered the businessman time to find a buyer. No buyer was found, the deal went ahead and a subsequent meeting between the Spanish company and Mr Quinn was said to be tense by those who attended.

Mr Quinn is adamant that the Mannok directors treated him badly. He names Mr Lunney, operations director, Liam McCaffrey, chief executive, Dara O’Reilly, chief financial officer and John McCartin, non-executive director and a former Fine Gael councillor.

Mr Quinn said: “They were supposed to buy the whole manufacturing business which was in, I suppose, about ten to twelve countries. Sure they bought nothing. Sold the glass, plastics, radiators, wind. All gone in 2014/2015. And they just managed the cement. Bought nothing, never spent the price of a bottle of water.”

Mr McCartin said the subsidiaries referred to were never part of the 2014 bid to bring back the Quinn Building Products and Quinn Packaging assets under local management. They were not sold by QIH but mostly sold by the receivers Aventus before the QIH deal, which Mr Quinn told the men he would support at the time of signing, was concluded.

Indeed, Mr Quinn accepted the role of a QIH adviser on a €500,000 salary. His son Seán Quinn Jnr would join on a €100,000-a-year deal. But Mr Quinn still saw himself as the boss, and it quickly became clear that he was unwilling to play any other role. He resigned his position after tension built from his demand of an immediate equity stake and accusing Mr McCaffrey of stealing from the business. Two investigations were carried out and Mr McCaffrey was exonerated.

Mr Quinn also believes businessmen John Bosco O’Hagan of Specialist Joinery Group in Maghera and Ernie Fisher, formerly of Co Fermanagh-based Fisher Engineering - who were crucial in driving through the purchase of QIH in 2014 via the vehicle Quinn Business Retention Company (QBRC) - have been blindsided.

“The glass [company] was the big one but also the plastics, radiators and windfarm,” says Mr Quinn. “They said they were doing this for Sean. Fact. I believe [John] Bosco [O’Hagan] and Ernie [Fisher] are decent men. But how they don’t know at this stage they were f’ed over I just don’t know? They must have seen what the mandate was.”

Mr O’Hagan maintains the buyout was a success and points to local jobs being saved and a local management team in place – Mr McCaffrey, Mr Lunney and Mr O’Reilly are all local men.

In an interview with The Irish News in 2019, Mr O’Hagan said that Mr Quinn’s bad behaviour led to a breakdown in relations.

"The Quinn men had very good salaries for their consulting activities,” Mr O’Hagan said. “The right team was in place and over the next four to five years we could drive the business to a point of buying out the American shareholders and Mr Quinn could come back again. That was the plan."

But he added “that was not how Sean Quinn saw things'' and relationships would deteriorate.

Mr O'Hagan is no longer on speaking terms with Mr Quinn.

Mr Quinn has repeatedly condemned the attack on Mr Lunney and any acts of violence done in his name. But he still despises the QIH directors.

Mr Quinn is seething with anger. A lot of what he says about his former friends during the interview can’t be published. His wife Patricia is even called into the kitchen during the interview to add weight to allegations made by Mr Quinn.

Mr Quinn said: “The abduction of Kevin was a barbaric act. I feel I have kept quiet for far too long… and I haven’t let it been known the harm they have done to me and the community and the destruction they have caused by giving the companies to foreign companies. All the tax and profits leaving the country.”

Mannok pays its tax in the jurisdictions it operates in, which are in the UK and Republic of Ireland, according to company accounts. Mannok posted an increase in EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation & amortisation) of 17 per cent from €26.6m (£23m) to €31.1m (28.7m) in 2020.

Mr Quinn says he has conducted hours of interviews for an RTE documentary which will air next year and which he believes will persuade people that he is the one who has been wronged.

“My reputation is more important than money,” he says. “Money was never important. Success was important to me. If you have no ambitions in life you are better dead. No point in living. Everyone has ambition, whether it is a woman getting a new dress or whatever. It was never money for me. I enjoyed building factories 37 years ago and employing people.”

Asked about the violence and intimidation that had been directed at his rivals, Mr Quinn emphasises the discontent in the community over the way he has been treated.

“Look, look if there is 1,000 people angry, it only takes one or two of them,” he says. “All of the farmers wouldn’t p**s on these boys if they were on fire. Not a farmer in the area or member of CFL [Cavan, Fermanagh and Leitrim Community Group established to support Seán Quinn] if they meet on the street would speak to these guys.”

The acts of sabotage began when liquidators moved in and changed the locks of Quinn Group in 2011. There was a period of relative calm around the time of the QIH deal in 2014. Since then there have been more than 70 acts of sabotage and destruction against the company, but with Lunney’s kidnapping something changed.

After almost a decade of little action, police in the Republic and Northern Ireland announced a cross-border operation to find the perpetrators. At dawn on November 8 2019 they broke down the door of the house in Buxton, in northern England, where Dublin Jimmy, the ex-IRA gangster, was hiding out.

While police searched the property, Dublin Jimmy sat on the sofa with a cup of tea and smoking cigarette. He then collapsed from a heart attack and was pronounced dead. Officers recovered documents, computers, and several mobile phones from the house.

Later that month four men were arrested and charged over the assault and false imprisonment of Mr Lunney.

“You’ve heard of Dublin Jimmy?,” Mr Quinn asks. “When they [the liquidators] came in in April 2011 taking over Quinn group he was in a Belgian prison so who organised the sabotage then? It couldn’t have been Dublin Jimmy. So who organised it? …I know who organised it…”

The claim he makes to the Irish News is unsubstantiated and will not be printed.

When asked if the return of violence against the Mannok (formerly QIH) directors was orchestrated by Dublin Jimmy, Mr Quinn says: “I don’t think so. It wasn’t Dublin Jimmy in 2011. So who came up with this thing that it was Dublin Jimmy in 2015?”

In August 2021, the Fermanagh Herald reported from a meeting of the Cavan/Fermanagh/Leitim Community Group in Ballinamore which Seán Quinn attended. The report said “many neighbours and former employees turned out”. It was the first such meeting since the easing of Covid restrictions and was led by the community group’s solicitor, Chris McGettigan.

The Fermanagh Herald said that Mr McGettigan told the meeting, that the gathering was about “maintaining and continuing its support for Seán Quinn” and reminded those at the Commercial Hotel in Ballinamore, that the “unheard of level of litigation against local people” was something the group was monitoring and would support individuals through.

When pressed if it is time to move on, Mr Quinn becomes frustrated and says he has said dozens of times that the violence has done nothing but hurt him and his family and says it is absolutely wrong. However, he cannot contain the bitter personal criticism he feels towards his former employees.

“You’re not asking the right questions,” Mr Quinn asserts. “I don’t mean to be offensive. I have spoken very little over past five to six years. They [The Mannok directors] have done all of talking – 97 to 98 per cent of it. Seán Quinn has done two or three per cent..."

“Now if Seán Quinn agreed with all [they said],” he added, “and said alright, they have plenty of raw material, they are decent men. Then there would have been no sabotage…. I said that was a pile of bull and then started to distribute the information a little bit better.”

Mr McCartin, a non executive director in Mannok, said: “We are not engaged in any feud. There is a criminal campaign being waged against us and until the identity of the person who procured and resourced the campaign against us is caught, this won’t end. Talk of community anger is, in my opinion, a smokescreen to distract from the question of who procured and resourced these attacks and is likely to do so again against us in the future.”

So it seems that it will be a sometime before calm reigns in this borderland community and a long time before Mr Quinn returns to Mass at his local church.

Follow Susan Thompson on Twitter @susanbutterwick