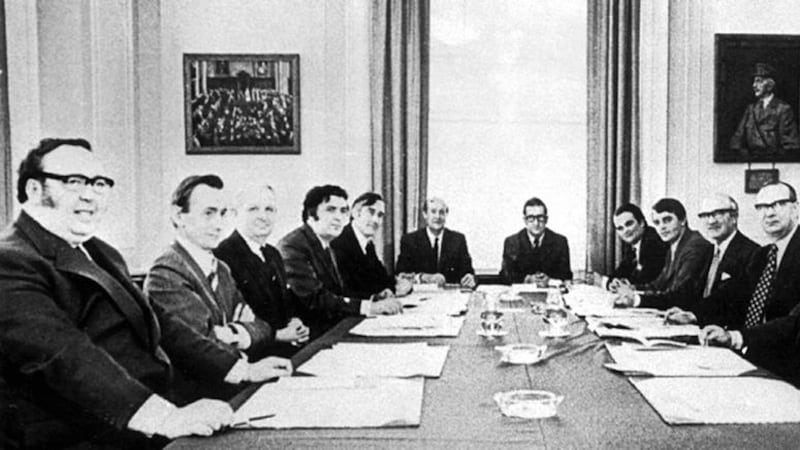

The ill-fated 1974 Executive had a more radical approach to educating Catholics and Protestants together than ministers today, an academic has claimed.

A research paper describes how the power-sharing government formed during the most bloodiest period of the Troubles supported ambitious integrated education policies to tackle segregation.

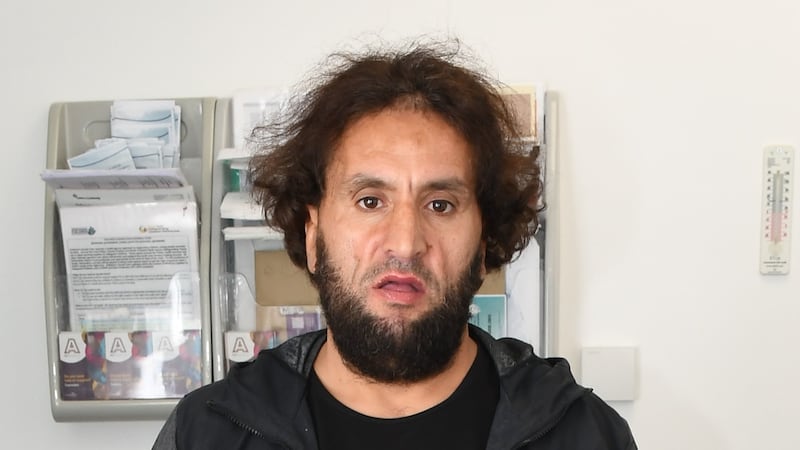

Dr Shaun McDaid said the challenges faced by contemporary policy makers are markedly similar to those of 40 years ago - minus the same level of violence.

However, he said the `post-conflict' Executive has embraced a model based on shared resources and facilities at the expense of truly shared education.

Dr McDaid, from the University of Huddersfield's Centre for Research in the Social Sciences, said there had been a drift away from integrated education to models where the only true sharing is of infrastructure.

While the Department of Education has a statutory duty to promote integrated schooling, much of the recent focus has been on promoting models of shared education.

In addition, education minister John O'Dowd has published guidance designed to support the establishment of schools which would be jointly-managed by Catholic and Protestant Churches.

The last new integrated school opened in 2007 and it has been four years since any school 'transformed' to integrated status.

Dr McDaid claimed that shared models are less likely to lead to the promotion, at an early age, of tolerance and mutual understanding between communities.

He said the first power-sharing executive, during a more difficult security climate, had a considerably more ambitious integrated education policy.

Although it lasted just five months, it formulated "one of the most progressive and ambitious strategies for integrated education in the history of Northern Ireland, aimed at strengthening community relations and developing greater respect and understanding between the communities".

The 1974 programme for government, Steps to a Better Tomorrow, made the link between integrated education and improving community relations explicit.

The new administration, it promised, would undertake "detailed investigation of the role of education in the promotion of community harmony and the development of pilot experiments in integrated education".

Then education minister Basil McIvor planned to introduce `shared schools', which would be fully integrated. Both Catholic and Protestant Churches would be represented on boards of management, although the Catholic Church was fundamentally opposed.

Dr McDaid said the Department of Education now used the shared term to "mean something quite different from fully integrated schooling".

"It is clear that the first Executive had much more expansive plans for integrated education than the current administration. This was despite the fact that it took office during the most violent years of the Northern Ireland conflict," he said.

"Admittedly, its proposals were costly and may have been too ambitious given the economic climate of the time. Nevertheless, they provide a portrait of an administration prepared to take radical decisions in order to grapple with a deep-seated societal problem, despite the potential costs, criticisms, and opposition that such an approach would bring.

"The present-day Executive has at least succeeded where the first failed, in being relatively successful in building the peace. However, in education policy as elsewhere, it has yet to demonstrate the capacity of managing the equally difficult task of fostering inter-communal reconciliation among the region’s divided communities."