A Mars rover built in the UK has taken a step closer towards its mission to search for life on the red planet after its upgraded parachute and bag system passed a series of tests.

The checks on the equipment were conducted by Nasa in California to determine whether it is fit for use in the harsh conditions of our neighbouring planet.

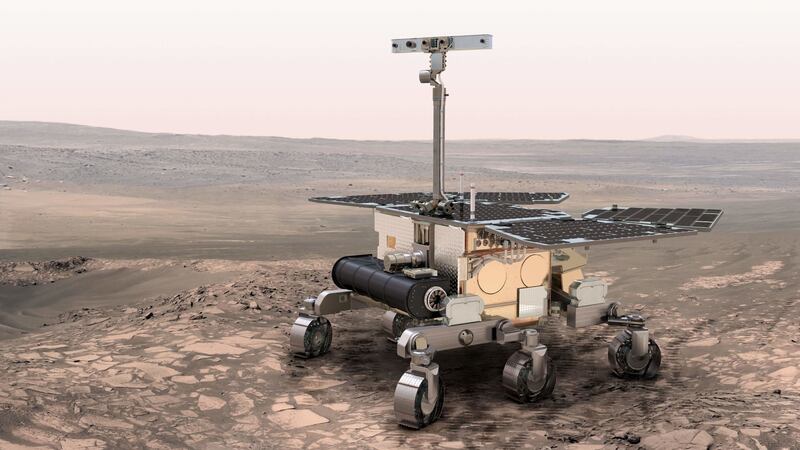

Formerly known as ExoMars, the Rosalind Franklin rover is a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Russian space agency, Roscosmos.

The latest round of tests focused on one of the two parachutes on the rover, which had components provided by parachute manufacturing companies Arescosmo and Airborne Systems.

Arescosmo provided a new bag design and a revised approach to folding to avoid line-twisting during parachute extraction while Airborne Systems supplied the parachute and bag system, according to the ESA.

Thierry Blancquaert, who is the team leader of the ESA’s ExoMars programme, said: “Both performed very well in the tests.”

He said there had been a few small areas in the parachute canopy which had been subject to friction, but added that the issue can be rectified in “just a couple of days”.

The Rosalind Franklin rover was built by Airbus Defence and Space at the company’s UK facility in Stevenage and is named after Rosalind Franklin, a UK scientist and co-discoverer of the structure of DNA.

The rover plays a key role in the ESA and Roscosmos’s two-part mission, the first of which – called the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) – was launched in 2016.

The aim of the TGO was to “sniff out” gases in the Martian atmosphere and look for evidence of methane – an indication of life on or below the planet’s surface.

Earlier this year, scientists from the UK’s Open University revealed that the TGO had found traces of water vapour, one of the key ingredients of life.

The second part of the ESA and Roscosmos’s Mars mission is expected to take place next year, with the launch of the Rosalind Franklin rover.

The 300kg-robotic vehicle was due to blast off in 2020 but engineers were not able to get the spacecraft ready on time.

Matters were further complicated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

In November 2020, the rover successfully completed its first full-scale high-altitude drop test, following two failed tests in the previous year.

As part of the next steps, it will perform another high-altitude drop test in early June from Kiruna, Sweden, which will see the rover dropped under the parachute from a balloon, at an altitude of about 29km.

Further ground-based tests are due in August to prepare for another pair of high-altitude drop tests later this year.

The Rosalind Franklin rover requires two main parachutes to help slow it down as it plunges through the Martian atmosphere.

Our next high-altitude drop tests are planned from Kiruna 🇸🇪 in May/June with new parachute canopies from Airborne Systems, who helped deliver @NASAPersevere to #Mars. Read more 👉https://t.co/luOUC2suUU #ExoMars pic.twitter.com/fAepCwRxRU

— @ESA_ExoMars (@ESA_ExoMars) March 5, 2021

When the spacecraft is 1km above ground, the braking engines will kick into gear and safely deliver it to the planet’s surface.

Chris Castelli, director of programmes at the UK Space Agency, said: “The Rosalind Franklin rover demonstrates the UK’s leading capabilities in robotics, space engineering and exploration, as well as our ongoing commitment to the European Space Agency.

“This exciting mission will search for signs of life on Mars and, we hope, inspire a generation with the wonders of space exploration.

“These parachute tests are vital in helping us get the technology right to ensure it is a success.”

Once on Mars, the rover will collect samples with a drill down to a depth of two metres and analyse them in an onboard laboratory.

The ESA said its aim will be to land the rover at a site “with high potential for finding well-preserved organic material” which may offer clues as to whether ancient life ever existed on the planet.