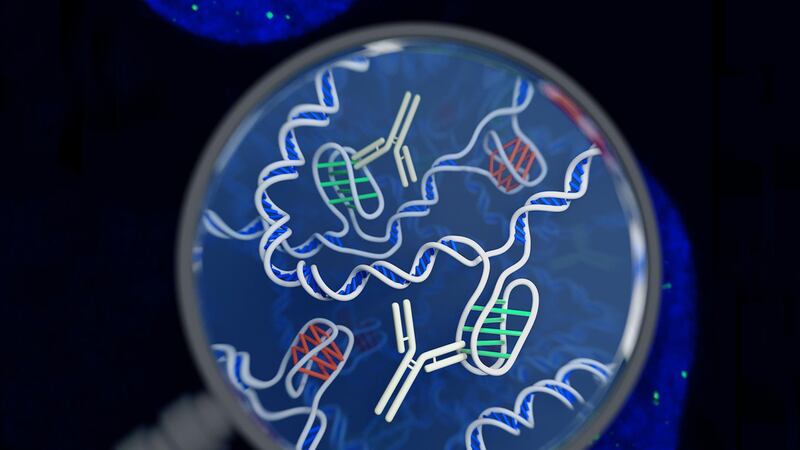

Scientists have identified a new DNA structure inside living human cells that looks like a twisted “knot”.

Called the i-motif, the DNA form has been described as “a four-stranded knot of DNA” and is different to the more well-known double helix structure.

The discovery was made by researchers from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia.

Associate professor Daniel Christ, who is head of the antibody therapeutics lab at Garvan Institute and one of the study authors, said: “When most of us think of DNA, we think of the double helix.

“This new research reminds us that totally different DNA structures exist – and could well be important for our cells.”

Scientists have seen the i-motif before – but only under artificial conditions in the laboratory and not inside living cells.

Although the function of the i-motif is not clear, the team believes it is involved in “reading” DNA sequences that contain the instructions needed for an organism to develop, survive and reproduce.

DNA is a complex chemical found in a cell’s nucleus that carries genetic information. This information is stored as a code made up of four chemical bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T).

In the double helix DNA structure, these bases pair up with each other – A binding with T and C binding with G. But that is not the case with the i-motif.

Associate professor Marcel Dinger, who is the head of Kinghorn Centre for Clinical Genomics at Garvan Institute and also a study author, said: “The i-motif is a four-stranded ‘knot’ of DNA.

“In the knot structure, C letters on the same strand of DNA bind to each other – so this is very different from a double helix, where ‘letters’ on opposite strands recognise each other, and where Cs bind to Gs.”

"Visualizing i-motif DNA"Our recent paper is out in @NatureChemistry . Check it out here: https://t.co/S0XDzac0Ou, if you are interested in non-B-DNA, i-motif, G-quadruplex and gene regulation.@MarcelDinger@GarvanInstitute the image courtesy of @cjhammang pic.twitter.com/kK8zBIhRUm

— Mahdi Zeraati (@Mahdi__Zeraati) April 23, 2018

To locate the i-motifs inside human cells, the scientists designed a tool using antibodies – Y-shaped proteins that bind with specific molecules – that attaches itself to i-motifs but not to any other form of DNA.

By using fluorescent dyes on the tool, the researchers identified numerous spots of green within the nucleus, indicating the position of the i-motifs.

Dr Mahdi Zeraati, a postdoctoral researcher at Garvan Institute and the first author of the study, said: “What excited us most is that we could see the green spots – the i-motifs – appearing and disappearing over time, so we know that they are forming, dissolving and forming again.

“We think the coming and going of the i-motifs is a clue to what they do. It seems likely that they are there to help switch genes on or off, and to affect whether a gene is actively read or not.”

The findings are published in the journal Nature Chemistry.