A fascinating video of ice being dropped 90 metres into an Antarctic glacier has been shared thousands of times on Twitter – and it’s sure to appeal to your inner child.

Climate scientist Peter Neff dropped the ice into the deep borehole and posted the video – for which you’ll certainly want the sound on.

🔊🔊Sound ON🔊🔊

When #science is done, it's fun to drop ice down a 90 m deep borehole in an #Antarctic 🇦🇶 #glacier ❄️. So satisfying when it hits the bottom.

Happy hump day. pic.twitter.com/dQtLPWQi7T

— Peter Neff (@peter_neff) February 28, 2018

“The resulting noise is so unexpected and fascinating,” Peter told the Press Association. “The holes are beautiful blue portals.”

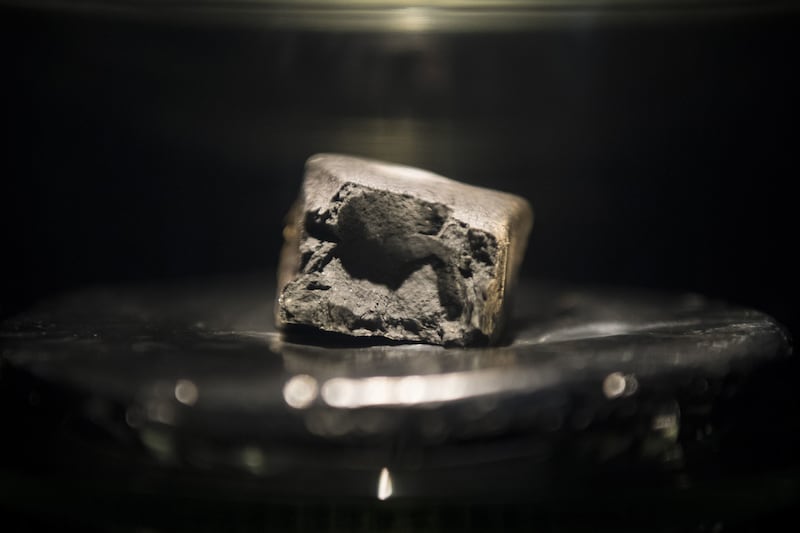

Those holes are from Taylor Glacier in the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica, where Peter and his team were drilling to recover ice cores and study the gases trapped inside.

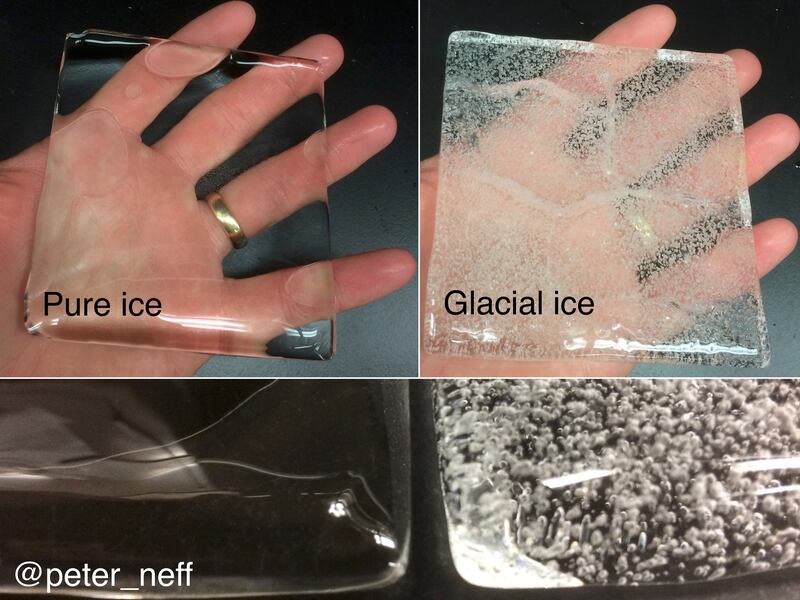

“Glacier ice traps ancient air, caught in the space between snowflakes as they are slowly compressed into ice,” Peter said. “You can nicely see this in the image I’ve included of pure ice made in the lab, versus a slice of bubbly glacier ice.”

“Because we actually study the types of carbon composing trace gases like CO2 (carbon dioxide), CH4 (methane), and CO (carbon monoxide), we need a large volume of ice,” said Peter. “Something like a ton of ice to get about 40 litres of air for analysis.

“Taylor Glacier is special because usually to get 50,000-year-old ice, we have to drill through 50,000 layers of annual snowfall – sometimes up to two miles deep.

“Those layers of snow, compressed into ice, are like a history book of past climate and past atmospheric composition.

“The ice at Taylor Glacier has flowed out of the ice sheet and actually flipped on its side, so we can effectively page through that history book, find the passage we want to study in detail, and drill multiple holes in that layer of ice to get very large samples. It’s called ‘horizontal’ ice coring.”

Lest you think we were able to control our glee while putting #Antarctic #glacier ice back in the borehole it came from… pic.twitter.com/hjLyZe8Bms

— Peter Neff (@peter_neff) February 28, 2018

Although the scientists use a number of holes, Peter says they close up quite quickly due to snowfall and the glacier’s ice flow.

The minimal risk of falling down one of the holes is worth it too, as you can learn an enormous amount from the ice.

“You can actually take the direct temperature of the ice, which still remembers the cold of the last Ice Age 20,000 years ago,” said Peter.

“This is kind of like when you pull your holiday ham out of the freezer and chuck it in the oven; the middle of the ham will still remember the cold of the freezer for however long it takes the oven heat to penetrate to the centre.”

Antarctic 🇦🇶 ice core drilling w/ @US_IceDrilling, @NSF_OPP allows us to 1) learn about Earth's past climate, 2) make cool noises in deep ice boreholes. pic.twitter.com/FIeSHcOOA9

— Peter Neff (@peter_neff) March 4, 2018

“There is an inherent beauty to ice and to the Antarctic, which is another reason those of us lucky enough to work there are drawn back,” added Peter.

“Antarctica is a big, beautiful, icy place that can tell us a lot about Earth’s climate history through this preserved ice, and will also play an outsized role in all of our futures through its continuing contributions to global sea level rise in a warming world.”

Katabatic winds at Taylor Glacier, Antarctica 🇦🇶, falling off the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Looks peaceful, but they're like a force of gravity. Drop a glove & it will be gone forever before hitting the ground! pic.twitter.com/xokbtLNBJz

— Peter Neff (@peter_neff) March 2, 2018

Peter and his team’s research is led by the University of Rochester and supported by the US National Science Foundation and Antarctic Programme.