Evidence of the brain’s waste drainage system has been found after being forgotten about for more than 200 years.

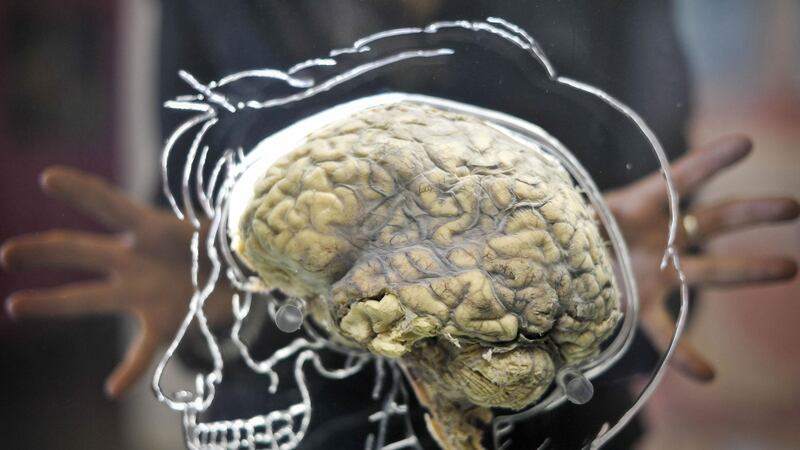

In 1816 an Italian anatomist reported finding lymphatic vessels – the body’s sewer system – on the surface of the brain.

But until researchers at the US National Institutes of Health used MRI scans specifically to look for them, scientists were puzzled as to how the brain drained waste.

Lymphatic vessels, which run alongside blood vessels and are part of the body’s circulatory system, transport immune cells and waste.

While blood vessels are delivering white blood cells to organs, the lymphatic system recirculates those cells around the rest of the body – a process that ensures the immune system is aware of any illnesses, viruses or injuries attacking the body. In short, they’re very important.

Until recently some scientists had thought the brain was an exceptional organ capable of drawing fluid but not needing to drain it, while others were sure the brain was draining waste but had no idea how.

Work by Dr Daniel Reich showed that not only does the brain use the lymphatic system to drain waste, but the vessels could also act as a pipeline between the brain and the immune system.

“For years we knew how fluid entered the brain. Now we may finally see that, like other organs in the body, brain fluid can drain out through the lymphatic system,” said Dr Reich, senior investigator at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

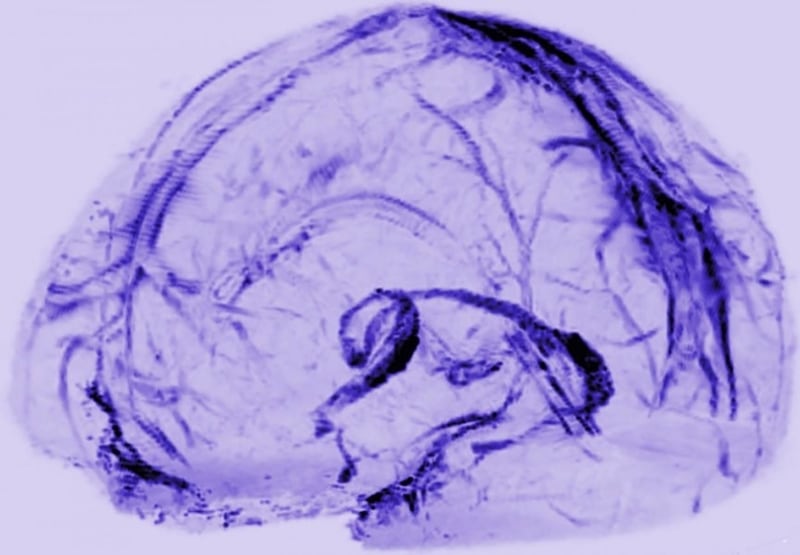

The researchers used magnetic research imaging (MRI) to discover the vessels, which were in the dura – the leathery outer coating of the brain.

Five healthy volunteers were injected with gadobutrol, a magnetic dye used to visualise brain diseases, whose molecules are small enough to leak out of blood vessels in the dura but too big to pass the blood-brain barrier and enter other parts of the brain.

At first they saw nothing out of the ordinary, just the dura lit up showing blood vessels.

But after tuning the scanner differently, to make the blood vessels disappear, the dura was still lit up with equally bright spots and the researchers suspected they’d found lymph vessels. The finding suggested that the dye had leaked from blood vessels into neighbouring lymph vessels.

Further scans using a different dye with bigger molecules that leaked less out of blood vessels followed, and this time no neighbouring vessels were discovered, confirming their suspicions.

They also found blood and lymph vessels in the dura of autopsied human brains, while scans and autopsies from non-human primates suggest the lymphatic system is a common feature of mammalian brains.

“These results could fundamentally change the way we think about how the brain and immune system inter-relate,” NINDS director Dr Walter Koroshetz said.

Dr Reich’s team plans to investigate whether the brain’s lymphatic system works differently in patients who have multiple sclerosis or other neuro-inflammatory disorders, among other things.

“We literally watched people’s brains drain fluid into these vessels,” Dr Reich said.

“We hope that our results provide new insights to a variety of neurological disorders.”

The research was published in the journal eLife.