FEW loyalist bandsmen can claim to have performed at the renowned traditional music festival, Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann. Fewer still can boast of having taken their case to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis. But Kenny McFarland is hardly your average bandsman.

The 61-year-old grandfather - who has drumming "in my blood" - chairs the Londonderry Bands Forum, which was formed in 2010 to challenge "prejudices and misconceptions" about the marching band community, and to tackle the social and educational challenges prevalent in Protestant-Unionist-Loyalist (PUL) communities in Northern Ireland.

"We always say culture can tackle the poverty of aspiration," he says. "In the Protestant community, there's a lack of aspiration."

Kenny was reared in a house directly across the road from the Orange Hall in Cullion, a tiny village in Tyrone. "If you were passing it now, you'd say it was a grand house, but it wasn't a grand house when we had it; it was actually a condemned house." While his father gravitated towards the Orange Order, the young Kenny was pulled in a different direction.

"I think I tortured everybody when I was young. If my mother sat two knitting needles down, I'd have been drumming," he remembers.

"I used to stay a lot with my grandfather. He was a drummer and I turned his head, to be quite honest, for everywhere I was standing I was drumming.

"My son, when he was younger, was like that. He could just pick up drumming - he's really good at it but he's not interested, he's into computers - but I've a grandson, Oliver, who's in the 'Orange and Blue' at present, and he's like myself, he's just drumming mad."

Kenny recalls the "buzz" he felt as an eight-year-old when he got to lead a pipe band. His exhilaration was short-lived. In 1968, the family moved to a new house, the former gate lodge of the old City & County Hospital, close to Derry's Bogside.

"I remember walking across to the shop, which was a real novelty - a shop at the end of the street - and meeting young boys and even then, they were saying, 'What church do you go to?'" he says.

"St Eugene's [Catholic] Cathedral dominated the street and I remember thinking I don't go there, I go to Donagheady, which is out in the country and it's not that size.

"And somebody said, 'You must be a Protestant, then?' I didn't know what I was.

"I knew I was Presbyterian, but I wasn't sure if that was the same thing. I remember having to go back and ask."

It was "an exciting place" to be in 1969 and 1970, as the solitary Protestant in the 'Celtic Blues' football team. "We played a match against a crowd from Rosemount, but they actually thought the Protestant was a different boy, so they were kicking him all over the place.

"Another thing that kept us going was searching for rubber bullets. There was always a notion that there were rubber bullets in St Eugene's Cathedral grounds, and I used to get sent in because they [his Catholic friends] were terrified of the priest.

"They didn't want to get caught but they thought, 'He can't do anything to you.' The Troubles goes over the head of an eight- or nine-year-old, but it must have been terrifying for my mother and my father."

His parents' fears were well-founded. "Things were getting really serious in 1971. There'd be sniping, bombs going off, they booby-trapped the backdoor of our yard with an incendiary device type of thing. It might have been a tripwire meant for soldiers."

Kenny recalls the mother of one of his friends telling him apologetically that they had been told the children weren't allowed to play with him. "It was a long walk home. I would say that was the start of our family looking to get away, then."

Three days into his first term at secondary school, Kenny was summoned to the headmaster's office to learn that the family were being uprooted again, this time to Newbuildings, a village just outside the city, that would swell with displaced Protestant families: "That was the world we lived in then and people got on with it and made do."

'Making do' in his new community included fundraising for the Foyle Defenders, a new band which was started in 1974. In the early 70s, Kenny says, the growth of these new bands was one of the most positive things happening in loyalist communities.

"I hear people saying it was like a pressure valve," he explains.

"Young people went out and did their parades and came home, and it released all that frustration.

"We were taught by a man called Billy Dennison. He was a drummer in the Thiepval Accordion Band, and they were a great drum corp. The fluters were taught by Billy Cairns - who was actually a cousin of my mother and he plays in the Hamilton - so, we were taught well."

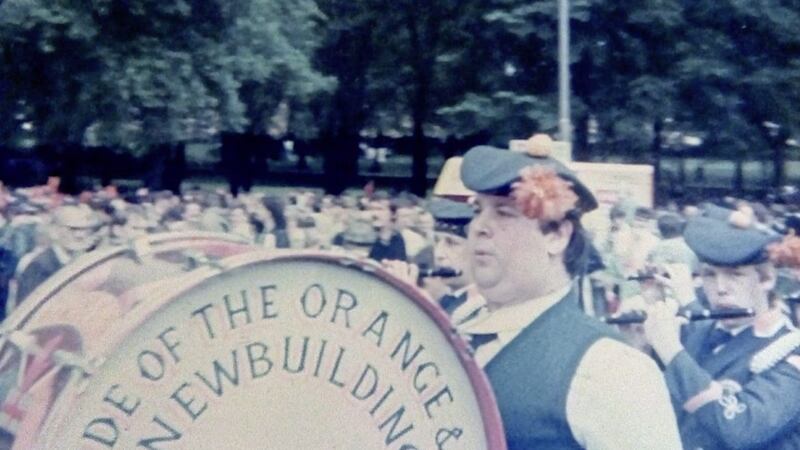

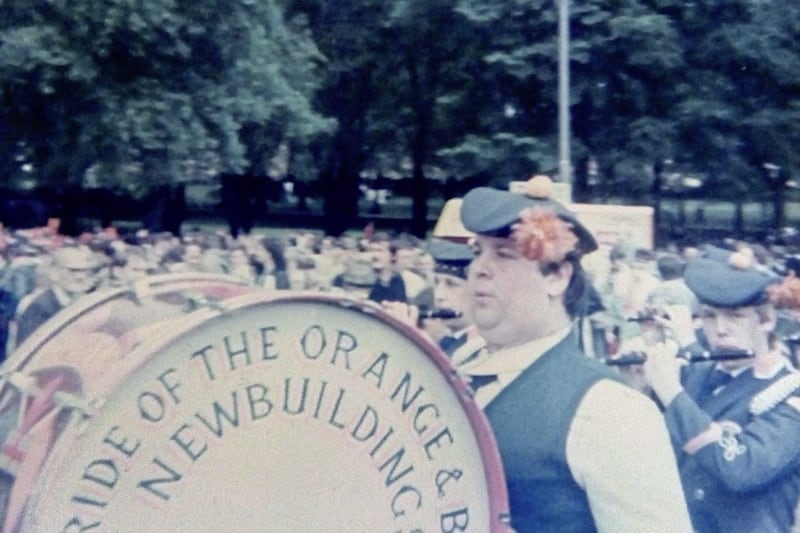

Five years later, Kenny and his friends started their own band, Pride of the Orange and Blue. "A band of 70 and no cars... People think they get it tight, now, but some of the stuff we did was mad. One of the first parades we did was out at Claudy. The [driver] must've had 13 or 14 in the car - [with] boys holding the bass drum onto the roof."

Bands performed a valuable role in communities like Newbuildings. "I remember doing a workshop with Mark Conway from Tyrone GAA and he said the two most important things in GAA are pride in place and legacy," says Kenny.

"He was saying, 'Your bands are like that.' And when I think about it, you know, there's a great pride coming from Newbuildings - a great pride in coming from Londonderry - when you're marching. We're representing our community.

"What people really don't understand is that it's those pounds - knocking on doors, the lottery, bonus balls, supporting a function - it's the community that funds the bands.

"When you walked on the Twelfth of July, down in Limavady or Coleraine, and there were all these people from Newbuildings there, you'd have heard them saying, 'There's our band, now'.

"So, there's a lot of pressure, and to be quite honest, if the band wasn't going well, people let you know about it. Thankfully, we didn't have many occasions where they could complain over the 40 years or so."

In recent years, the atmosphere around loyal order parades in Derry has been transformed, thanks to an agreement between the Apprentice Boys of Derry, the Bogside Residents Group and wider civic society, and then the development of the Maiden City Accord, a protocol the Bands Forum was instrumental in drawing up. It makes parade organisers responsible for participants' behaviour and has resulted in much lower-level security and few, if any, protesters.

The 80s and 90s were markedly different, though. Then, parades were tense affairs. There were stand-offs between rival groups; spitting and catcalling were commonplace; and marches were often followed by serious rioting.

It's not an era Kenny wishes to return to. "The main thing for us was being the best band - we wanted to be better than any band in the town, that type of thing - but when you were coming up, especially coming back to the Memorial Hall at night, it was all about defiance, I reckon," he says.

"It was about saying: 'You will not stop us,' you know what I mean? 'This is our city.'

"When you actually see footage of what the Diamond [in the centre of Derry] looked like in those days, it shows you what 'normality' was to us. Normality was so mad.

"You're marching up Ferryquay Street, and you'd all the loyalists on one side and all the nationalists on the other side, and the spitting and the booing and all that there, but it gave you such a flipping buzz.

"I used to say, it's the closest we'll ever get to running out in an Old Firm game. It was a real buzz, no doubt about it, but it wasn't good."

Groups like the Londonderry Bands Forum have been involved in changing the attitude "from defiance back to commemoration", explains Kenny.

"But at that particular time, really, for us as bandsmen, it was about discipline, making sure we didn't react; the media weren't there to cover people spitting at us, they were there to cover us reacting," he says.

"You went back to 'the Mem' [Memorial Hall] and people were raging, and all that sort of stuff, some of them covered in spit, but you didn't react. There was an ugliness about it but at the same time we just wanted to be playing well.

"An individual could do whatever he wanted but when he did it in a band uniform it brought stuff onto the band - reputation, stuff like that. When I look back, very rarely did things get out of hand."

The atmosphere has changed to such a degree that in recent years, children - including Kenny's grandson when he was "five, six, seven" - have been able to take part in the parades.

"He wouldn't have done that 30 years ago, 40 years ago. You just wouldn't have allowed young people up there," says Kenny.

"But it was what it was. You'd never want to see that back again. Now, on a Saturday - going to some of those Parent Club days, where you march over to the Memorial Hall - there's two or three policemen, people standing watching, it's hard to believe how good it is.

"It's a credit to the Apprentice Boys. They took big risks and they got that sorted."

The Londonderry Bands Forum has also taken risks. In 2013, it was persuaded to get involved in the All-Ireland Fleadh, which took place in Derry for the first time and drew thousands of visitors from across the island.

For many it was a first opportunity to hear a live marching band. The Londonderry Bands Forum's been evangelising ever since. In 2015, Kenny was one of three LBF representatives who attended the Sinn Fe?in Ard Fheis, garnering widespread media coverage for their presentation on marching bands.

The Forum is particularly visible - and audible - during Community Relations Week, running workshops in Catholic schools, giving students the chance to play flutes and drums, and learn about band culture.

At Christmas past, when Covid forced the cancellation of their now traditional festive concert in the Guildhall, local bands and guests took turns each night to perform Twelve Days of Christmas online.

"Events like the Fleadh, the Walled City Tattoo [in 2013] and the Christmas concert give bands the chance to show how good they are," Kenny says. They have shown marching bands in a different light - challenging "prejudices and misconceptions" on both sides.

He recalls his own band going to Sligo for the 2014 Fleadh. "After the parade, they [the band members] went in and changed and went into the bar, and the bar was full of musicians.

"There was the usual banter. They said, 'Where's your instruments?' 'Oh, they're on the bus.' 'Your instruments shouldn't be on the bus - bring them in here.'

"So, there's a great video of them all playing The Sash, and there were boys playing the spoons and fiddles, and that's an eye-opener for our concept of how people look at us."

Kenny no longer drums with the Orange and Blue, but as president he takes huge enjoyment in their musicianship, and pride in the fact that leadership has been passed to another generation. Legacy and pride in place. People can be far more alike than they think.

Interview conducted by Paul McFadden for the 'Protestantism: a Journey in Self-belief' project at Maynooth University. Reproduced by permission of The Church of Ireland Gazette.