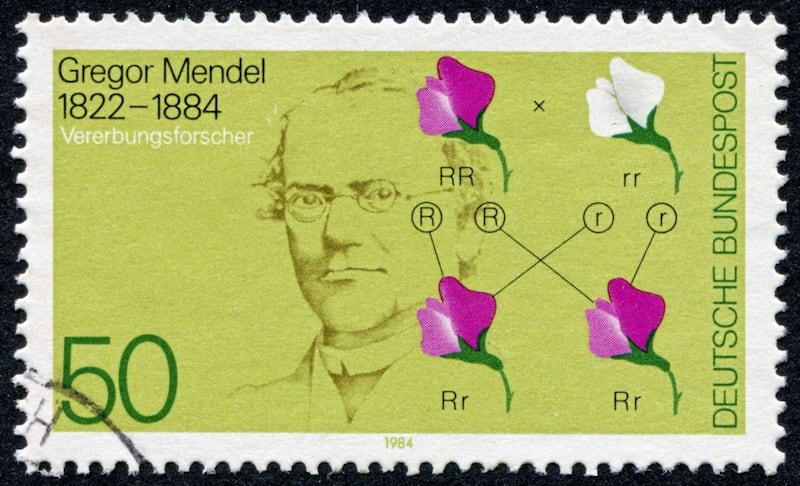

OUR knowledge of biology has exploded in the past 150 years, in part thanks to work of a priest who joined an Augustinian monastery in Brno - then in Moravia, today in the Czech Republic - in 1843.

His name was Gregor Johann Mendel. A compassionate but fragile individual, he was considered a slow learner, so he took to the greenhouse and began growing different strains of peas - 34 in all - analysing their traits and recognising distinctive patterns over the course of thousands of pea crossing experiments.

In solitary silence he would recognise laws behind seeming lawlessness.

After publishing his findings in an obscure journal in 1865, it would be over 30 years before the scientific field would become aware of his monumental results which revealed the most essential features of a gene.

Gregor Mendel is now known as the "father of genetics". Christians can be proud of the way this gentle man advanced science.

There have been many positive applications of Mendel's discoveries in genetics to improve the human condition.

A powerful example is the treatment of diabetes.

This illness results from being unable to produce correct amounts of a hormone called insulin, which regulates our blood glucose levels.

In the 1920s scientists were able to isolate small amounts of insulin from cows.

But this method had two major limitations - many people had allergic reactions to the low quality insulin obtained from cows, and the production process was hugely inefficient.

Thanks to a deeper understand of genetics, scientists now understand that insulin can be safely, consistently and effectively produced outside of the human body.

This has enabled millions of people to be treated for the disease and insulin is now recognised as one of the most important medicines in a basic healthcare system.

The production of hormones such as insulin outside the human body represented a crucial transition in the history of medicine.

Sadly in some instances genetics has been used negatively, for example, to disadvantage the weak through selective sterilisations.

One such instance occurred in the United States in the spring of 1920 when Emma Buck was brought to the 'Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded' in Lynchburg, Virginia.

This was an institution for people in what were then regarded as the three categories of 'feeblemindedness': idiot, moron and imbecile.

In practice, the words were used to classify primarily poor people whose behaviour fell outside the accepted norms of society.

Emma Buck, a single mother to Carrie, had been found on the streets and after a mental examination classified as 'feebleminded' and packed off to the colony in Lynchburg.

Carrie was placed in foster care. She was raped by her foster parents' nephew and became pregnant.

To stem the embarrassment, Carrie's foster parents had her committed to the same colony as her mother.

Dr Albert Priddy, superintendent of the colony, was a key figure in not only promoting but carrying out 'eugenic sterilisations' of the 'feebleminded'.

Having a mother and daughter both committed to the facility supported his theory that 'feeblemindedness' was hereditary; and if that was the case, Priddy and others argued, then 'eugenic sterilisation' was a way of limiting the 'genetic threat' the 'feebleminded' posed to society.

The colony's board of directors approved Priddy's application to sterilise Carrie but that decision was appealed by her legal guardian.

The case eventually rose to the US Supreme Court, which in May 1927 handed down an 8-1 majority result in favour of sterilisation, saying it was in the state's interests.

The Christian way invites us to find compassionate solutions for each and every member of society

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the judge who wrote the ruling, reasoned: "It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.

"The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes."

Holmes was evidently tired of the Bucks and their babies. "Three generations of imbeciles is enough," he wrote; Carrie was sterilised on October 19 1927. Her daughter, Vivian, died in 1932 from an infection after contracting measles. The episode is a prime example of genetics being used cruelly in a supposedly advanced society like the US.

Growing up in a poor society lacking in compassion, the experiences of the Buck family has many parallels with those of mothers and children living in Ireland at the same time.

The medical innovations helped by the enlightened work of Mendel should have enabled mothers and children to grow up healthier and happier. But poverty and a lack of compassion led to huge suffering.

One hundred years later, the economic poverty of 1920s America and Ireland has receded but a lack of compassion within society remains a problem.

Writing recently in The Irish Times, Melanie McDonagh noted that her father was handed over a shop counter by his aunt when he was just a day old.

She recalls: "My father was not a wanted child - that is, by his family - but he did at least get to be born. He might not now."

She laments the fact that with growing wealth and state power, society now supports abortion as a solution.

The Christian way invites us to find compassionate solutions for each and every member of society.

It takes courage to recognise the natural world's complexity. Mendel knew this well.

But more than courage, something else is evident in his scientific work that one can only describe as tenderness.

Tenderness shares its roots of course with tending, a gardener’s activity; Mendel was first and foremost a gardener.

In order to more fully enrich humanity we need moral guidance to tenderly navigate our complex world.

Dr Brian Wilson grew up in Ballymena, Co Antrim, completed undergraduate studies in Chemistry at Imperial College London and holds a PhD in Organic Chemistry from the University of Oxford.