THE Scottish government was recently advised by consultants that any promotion of Scotland must avoid two topics: God and golf.

I have little doubt that Thomas Chalmers would have been annoyed at such advice - he was one of the greatest leaders of 19th century Scottish Presbyterianism and during his time as a professor at St Andrews University he was a frequent golfer.

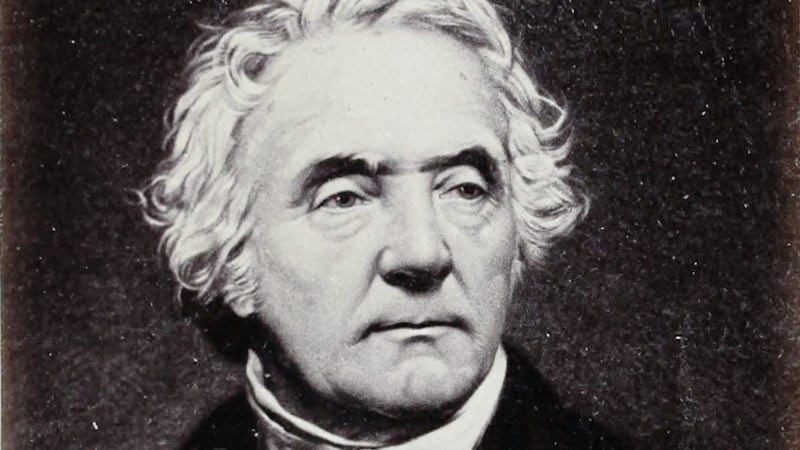

Professor Thomas Devine, perhaps Scotland's leading contemporary historian, argued that Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) was the most influential Scot of the 19th century.

That influence arose partly because his interests were so diverse and he contributed to all the great political debates of his day.

As we wrestle in 2019 with the relationship of Church and State, particularly in terms of whether the internal life of the Church should be subject to secular legislation, it is worth remembering that Chalmers and his contemporaries faced the same issue

He wrote about astronomy and economics. Every time you fill in your tax return gives thanks to Chalmers for inventing what we now call the income tax personal allowance: back in the 1800s Chalmers reckoned the first £60 of income should be exempted from tax; today that allowance is worth £12,500.

Having recently published a biography of Chalmers I think there are many reasons why we should seek to be more familiar with his life:

:: His views about Ireland were interesting - not least because he was a friend of such contrasting characters as Daniel O'Connell and Henry Cooke.

Unlike Henry Cooke, he recommended caution in the speed with which Arianism - a denial of Christ's divinity - was pushed out of the Irish Church.

Cooke, to his credit, was also a more forthright critic of slavery than Chalmers but Chalmers was much less enamoured than Cooke by the goal of aligning Presbyterianism with political conservativism.

Chalmers, unlike Cooke, did support Catholic emancipation.

:: He was a great preacher.

It was not just that on one occasion the army had to be used to control the crowds flocking to Chalmers's church in Glasgow, or that his sermons in London moved prime ministers.

The Holy Spirit worked through what was an apparently unimpressive pulpit style - Chalmers's usual practice seems to have been to read out a script word for word.

:: We have some insight into Chalmers's devotional life. From 1841 to 1847 he wrote daily Bible readings and weekly Sabbath ones.

He admitted his temptations - pride, temper and, unusually, what he viewed as an "excessive love for mathematics".

Unlike some other 19th century Scottish Presbyterians he had a lot of time for some other Church traditions, notably evangelical Anglicanism.

:: His publication record was massive. The William Collins publishing house, now part of HarperCollins, was started to provide a home for his many books.

:: Some modern ideas about the relationship between science and Christianity were anticipated by Chalmers.

He used phrases like 'intelligent designer'.

:: In the Glasgow of 1810s-20s and Edinburgh of the 1840s Chalmers led a last ditch defence of the traditional way of dealing with poverty whereby money was collected through the churches and disbursed at the parish level.

This defence ended in failure. Poor Law reform, the workhouses and all that went with it, continued in Scotland as in England and Ireland.

Chalmers, however, correctly predicted some of the problems which would follow from relying on the state and what we now call the welfare state.

:: As we wrestle in 2019 with the relationship of Church and State, particularly in terms of whether the internal life of the Church should be subject to secular legislation, it is worth remembering that Chalmers and his contemporaries faced the same issue.

When Parliament claimed that it had the supreme authority on the question as to how far landlords might use power of patronage to overrule the decision of each congregation as to which man to 'call' to become their minister, Chalmers and his colleagues felt they had to quit the Church of Scotland.

Hence the Disruption of 1843 leading to the creation of the Free Church.

There was a great irony in all of this. Chalmers, who had spent decades struggling to ensure a Christian influence across the entire Scottish (and British) nation now found that his actions in terms of splitting the Church of Scotland led to a reduction of its influence.

That said, the issue of principle was so strong that Chalmers probably had little alternative.

:: To the end of his life Chalmers remained a strong advocate of the Church Establishment principle - that there should be a Protestant Church supported by the state.

In more recent decades, support for establishment has waned amongst Christians; because of the special circumstances within American Presbyterianism post-1776, such beliefs were never strong in the USA.

We should, however, reflect on why Chalmers was such a strong advocate of Establishment.

:: I entitled my book Thomas Chalmers and the Struggle for a Christian Nation.

Chalmers really did place an infinite value on individual souls and he also wished to see all areas of Scottish and British national life subject to a strong Christian influence.

Two centuries on from Chalmers we have an even greater need for that influence.

Esmond Birnie is senior economist at Ulster University and was previously an MLA, ministerial special advisor and chief economist with PwC in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

He is the author of Thomas Chalmers and the Struggle for a Christian Nation. The book, priced £9.99, is available from the Evangelical Bookshop, College Square East, Belfast, BT1 6DD, telephone 028 9032 0529.