THIS document-based study begins with an account of the establishment of the first Our Lady of Charity Refuge in Dublin.

At the request of Fr John Smith of Saint Michael and Saint John's parish, four sisters and a novice from the convent of Notre Dame de Charite in Caen in Normandy took possession of No 2 Drumcondra Road in September 1853.

The sisters found the early years in the new foundation challenging, owing mainly to the tendency of Fr Smith to interfere in their daily routine.

However, after Dr Bartholomew Woodlock, president of nearby All Hallows College, was appointed their spiritual director and following a transfer to High Park, their work in caring for women, girls and children on the margins of society began in earnest.

The sisters at High Park were strongly influenced by the constitutions and traditions of the mother house at Caen, which had been founded in 1641 by St John Eudes; he was canonised in 1925.

As set out by the founder, its aim was to provide a house, where women who wished to turn their lives around from crime or prostitution could feel safe and secure.

Between 1641 and 1891, 34 other foundations were established throughout Europe, the United States and Canada.

Sisters from High Park established the Refuge at Gloucester Street/Seán MacDermott Street in 1887 and foundations at Kilmacud and Kill of the Grange in 1944 and 1956.

Prunty refers to the media-driven distorted and negative image of the sisters and their work among the public at large. Typical of this distortion is Peter Mullan's The Magdalene Sisters, where the nuns are portrayed as sadists, punishing young girls with impunity and in the name of religion

At the convent in Angers in France some changes were made to the constitutions and thereafter it became the motherhouse of what became known as Good Shepherd convents.

Others were opened in Ireland: Waterford in 1858, New Ross in 1860, Belfast in 1867 and Cork in 1870.

Jacinta Prunty details the developments at High Park from 1853 onwards.

St Joseph's, a reformatory school, was established in 1859. At different times it cared for up to 80 children.

It morphed into an industrial school in 1927 and became a national school in 1941-55.

Because of endemic poverty, severe want and neglect, children found themselves in this and other industrial schools. They simply had nowhere else to go for assistance.

Every aspect of life in those schools is examined by the author with copious references to official reports and the conclusions of frequent inspections.

Of particular interest were the development of hostels and teenage units in all three monasteries at High Park, Seán MacDermott Street and St Anne's, Kilmacud.

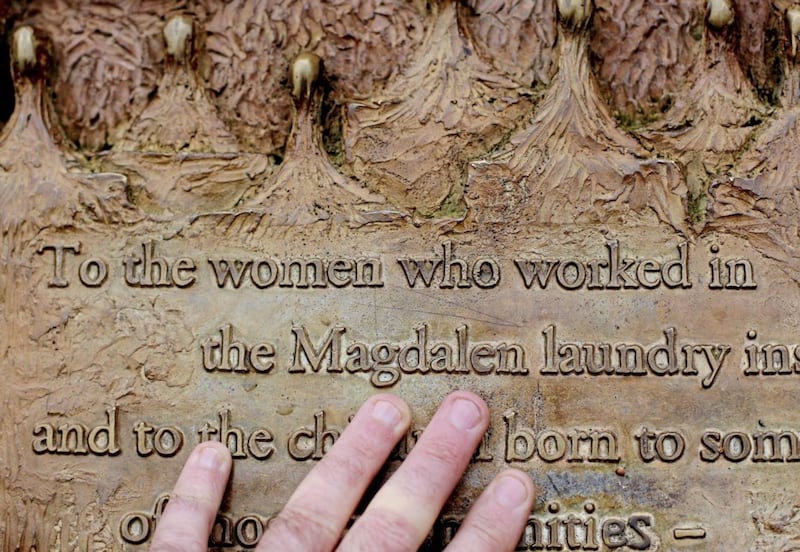

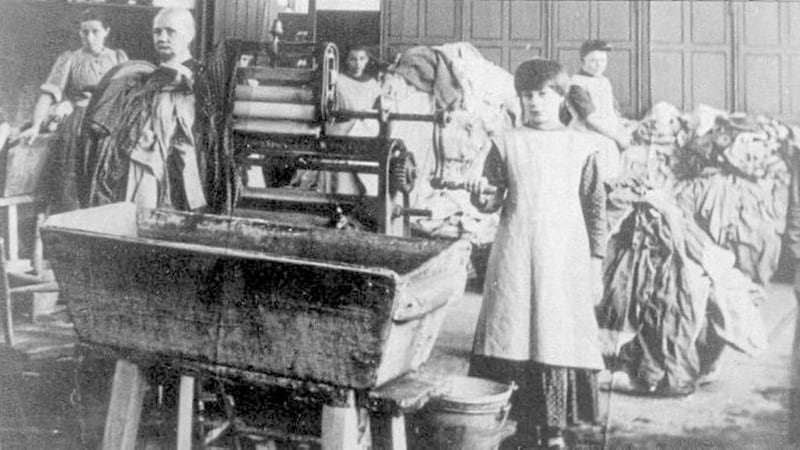

Very often the Our Lady of Charity Refuges are referred to as Magdalene laundries.

The author records that the sisters who ran these refuges were dismissive of the term laundries; laundries were simply a means for generating an income and in them the sisters worked side by side with the women and girls in the refuge.

Prunty refers to the media-driven distorted and negative image of the sisters and their work among the public at large.

Typical of this distortion is Peter Mullan's The Magdalene Sisters, where the nuns are portrayed as sadists, punishing young girls with impunity and in the name of religion.

More than most, the sisters have been the victims of so-called 'fake news'.

In one of the excellent illustrations in the book there is a classic example of this.

It depicts the May Procession in Seán MacDermott Street parish in 1965, in which women and girls from the refuge, clad in their Child of Mary cloaks, are walking. Also walking in this procession are members of the Gardaí.

A number of media outlets and at least one 'scholarly' work claimed that the picture showed that the Gardaí were on duty to prevent the women and the girls from escaping the clutches of the nuns.

I found Jacinta Prunty's account of the institutions of the congregation of Our Lady of Charity both magisterial and immensely satisfying.

But here I must declare a personal interest. With other duties I served in the 1960s as chaplain to St Mary's Magdalen Home in Donnybrook, which was conducted by the Religious Sisters of Charity.

I witnessed at first hand the generosity of the sisters as they spent their lives helping the women and girls in their charge and noted their solicitude for each one of them.

Hopefully this comprehensive and meticulously researched monograph will help people realise what a debt is owed to the sisters of the institutions of Our Lady of Charity and the other sisters engaged in the refuge ministry for caring for some of the most deprived and vulnerable members of our society during the past 150 years.

- The Monasteries, Magdalen Asylums and Reformatory Schools of Our Lady of Charity in Ireland 1853-1973 by Jacinta Prunty is published by Columba Press.

- Fr J Anthony Gaughan is a priest in the Archdiocese of Dublin. He has written widely on theology and history, including volumes on the archbishops, bishops and priests of the diocese since the 17th century.