WHILE the faithful departed are remembered in every Mass, it is in the month of November that the Catholic community places particular emphasis on commemorating the dead.

Such commemoration certainly includes giving thanks to God for the lives of the deceased.

But, as far as Catholic cultures at least are concerned, uppermost in people's minds in the month of November is the hope that the dead will finally attain to the fullness of eternal glory.

It is a month in which the Catholic religious mind is directed, in other words, more to the future than to the past.

Some may well find any explicit concentration on death somewhat lugubrious, and think it would be actually more in tune with 'real Christianity' to concentrate on life and what happens before, rather than after, death.

That is an understandable reaction to an earlier, possibly excessive obsession with death and its aftermath.

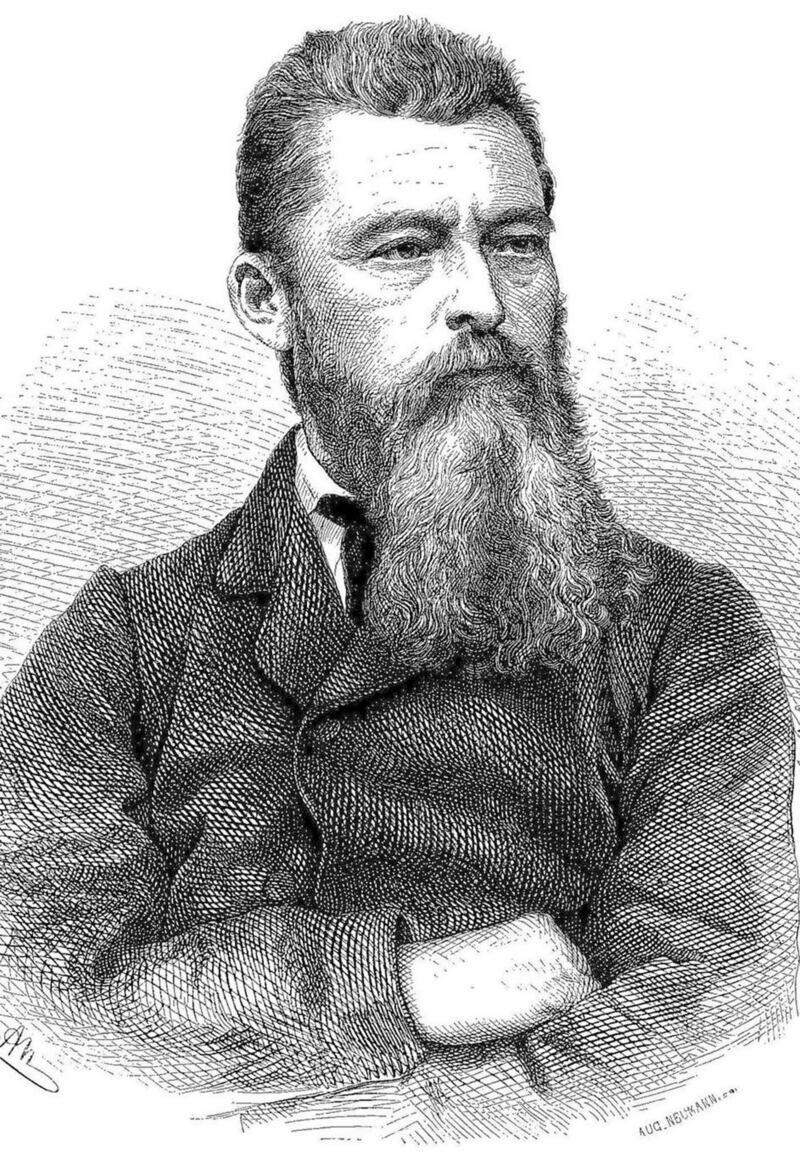

Yet one of the most influential, if controversial, thinkers on religion in recent centuries, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-72), who is usually identified with the notion of religion as 'projection' or wish-fulfilment, was of the view that "Man's tomb is the sole birthplace of the gods".

According to Feuerbach: "If man did not die, if he lived forever, if there were no such thing as death, there would be no religion."

Historically, the situation might be a bit more complex.

If religion is really born out of a desire to overcome death, how could one explain, for example, the faith of the Sadducees mentioned in the Gospels, who were certainly religious but had no belief in any resurrection?

November is a month in which the Catholic religious mind is directed more to the future than to the past

Nonetheless, Feuerbach's claim would appear to be relevant to Western Christianity as it developed over the centuries, and which did and does hold out hope in eternal life to its followers.

In the month of November, then, it might be helpful to reflect a little on what life after death might entail.

In a scene in Matthew's Gospel evoking the Last Judgement at the end of the world, Jesus is quoted as saying: "Come, you who are blessed by my Father; inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world" (25:34).

What might be meant by this?

Perhaps the most interesting feature of this short passage is the way it looks, from our human perspective, in two different directions at once, both to the future and to the past.

If the 'last things' are traditionally considered to be shorthand for humanity's eternal destiny, this forward and backward look at the 'last things' may seem odd or unexpected.

It's often said, for instance, when someone dies, that they have entered into eternity. That way of envisaging eternity is of course valid.

But it might also encourage us to focus on eternity as lying exclusively in the future, ahead of us.

Whereas an implication of the passage just quoted - when Jesus talks of the "kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world" - is that eternity also lies behind us.

If we believe God is eternal, and his kingdom is eternal, then that divine kingdom can't or won't just begin at some point in the future.

It always existed, and so Jesus can say that the kingdom promised to us was prepared from the foundation of the world.

In the First Letter of Peter (1:20) the same idea occurs, when reference is made to the Lamb of God who "was chosen before the creation of the world", and again it's an idea found in the last book of the Bible, the Book of Revelation (13:8), where we hear about "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world".

What this all seems to indicate is that God didn't just suddenly get a new idea about what to do with his creation after he created it.

Rather, the eternal destiny we pray for in the case of all the faithful departed and hope for in the case of ourselves, was one intended by God from all eternity, even before the world was made.

In that sense, November's commemoration of the dead, which can tend to induce a mood of gloom, fixated on death and loss, is fundamentally a hopeful celebration of God's mysterious power and redemptive goodness.

No-one would wish to deny that death and loss are profound realities, but that in turn only proves that our lives are not things of no significance, but are of inestimable value and depth.

And Christian faith teaches that that is ultimately true because those lives are eternally valuable in God's eyes.

To borrow a line from William Blake: "Eternity is in love with the productions of time."

Hence, in the month of November we can refresh our belief and hope that just as God has brought us into existence out of eternity, he can also be relied on to bring the work he began in us and in all the faithful departed to fulfilment in his eternal kingdom, which was as real before he created us as it will be after we have departed this life.

- Martin Henry, a former lecturer in theology at St Patrick's College, Maynooth, is a priest of the diocese of Down and Connor.