POPE Francis's first official pastoral visit outside Rome was to the island of Lampedusa. He cast a wreath into the water to remember people who had drowned while trying to reach Europe.

I met the island's priest as part of an ecumenical delegation visiting the work of the Mediterranean Hope charity on Lampedusa and the larger island of Sicily.

Dom Carmelo La Magra has been in post for six months and will shortly go to Rome to brief the Pope about developments in on the island.

He described meeting "the real flesh of Christ" in his encounters with the migrants who arrive on the island and stay for a few days or weeks before being ferried to Sicily and dispersed across Italy.

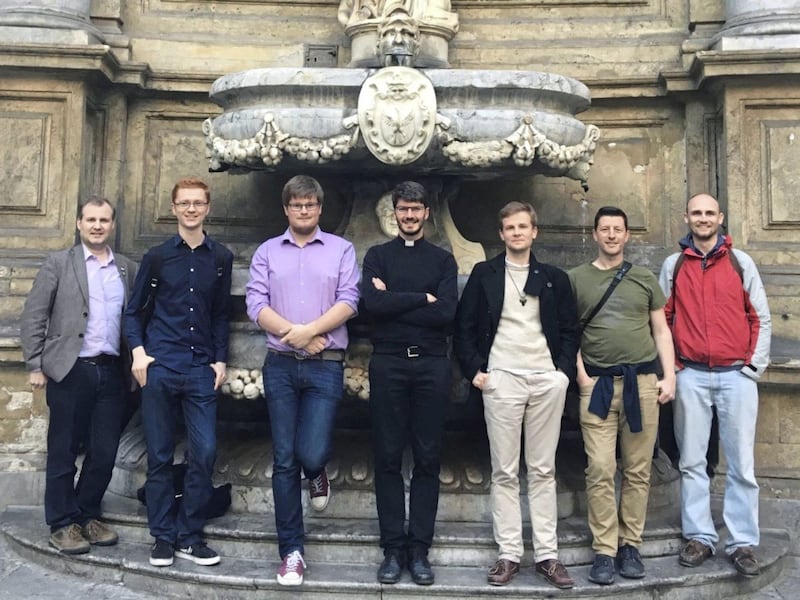

Having previously taken a group of women to meet with women and families in refugee camps and projects in Greece, this year Churches Together in Britain and Ireland (CTBI) deliberately chose to bring a team of young men in their twenties to Italy.

We wanted the team, each of whom was connected with a different denomination, to encounter the men of a similar age who make up the majority of the refugees making the journey by sea to Europe.

We went to show solidarity with those whom fear, danger, increasing poverty and despair have led to embark on dangerous journeys with no guaranteed outcome.

With our presence we sought to support the churches, NGOs, volunteers and local people who have responded, often where governments cannot or will not, and, often at cost to themselves, with generosity, humanity and compassion.

During the day, migrants often sit in the paved square in front of the large church building on Lampedusa's main pedestrianised thoroughfare.

"For all Christian people, this is the place they can call 'home', for Catholics and others too," the priest explained.

Coming inside to sit and pray, Dom Carmelo noted that at times the refugees cry so much that the stone floor is "bathed with their tears".

"We provide toilets, new clothes, shelter in bad conditions - all things we take for granted, but they do not because they have lost everything," he said.

In 2016, 181,436 people arrived by sea in Italy. Around 90 per cent departed from the coast of Libya to sail across the 460 kilometres to the island of Lampedusa, the southernmost part of Italy and the closest European landmass to Libya.

"We provide toilets, new clothes, shelter in bad conditions - all things we take for granted, but they do not because they have lost everything"

A total of 4,578 people - one in 40 - are thought to have died making this Central Mediterranean sea crossing last year.

The Catholic parish has joined in solidarity with the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy (FCEI) charity Mediterranean Hope to reach out to welcome refugees as they arrived on Italian shores.

In past years, refugees boarded old Libyan fishing boats - hundreds crammed below deck and hundreds above in the open air - and sailed all the way to the beautiful beaches of Lampedusa.

More recently, smugglers cram up to 150 people into an inflatable rib with just enough fuel to get beyond territorial waters. They then use a satellite phone to call the Italian Coastguard for help.

Mediterranean Hope offers a welcome, complete with sweet African tea and food to sustain the weary travellers stepping off the modern self-righting search and rescue vessels. who may have to wait for several hours on the quayside before being taken to the sometimes overcrowded hotspot accommodation.

Lampedusa has a population of 6,000 and covers an area of 20 sq km, making it a third larger than Rathlin Island.

The island people have been welcoming seafarers to their shores for hundreds of years. The caves set into the hillside at Sanctuary of Madonna di Porto Salvo were reportedly once home to a hermit who invited visiting ships' crews in for Christian or Muslim blessing, and exchanged rope and wood for food.

In modern times, fishing remains an important part of the island's economy and the dangers of the sea are well known to the population. Less than three month's after the Pope's visit, a tragedy struck the island.

A boat carrying migrants sank off Lampedusa's shores on October 3 2013. Local people helped rescue 155 migrants from the water.

Boats had sunk before. But the enormous loss of more than 360 lives awoke in the local community a new focus to respond to the needs of the migrants.

I noticed no attempt by islanders to label visitors as 'good' or 'bad' refugees. Nor was their backstory and the likelihood of making a successful asylum application a factor in the level of hospitality offered. Instead, refugees were simply welcomed as they were, independent of their likely past or probable future.

This acceptance and generosity sharply contrasts with the state's response. The hotspot was originally built for 380 people but has a stated capacity of 500.

However, at peak times, the identification centre has held more than double this number, with people forced to sleep outside.

On Lampedusa, we chatted to young men who had recently arrived on the island. Many slipped out through the fence that surrounded the hotspot and walked down to the harbour to hang out and enjoy the cooler breeze.

These men from Nigeria, The Gambia and Senegal explained their harrowing journeys from home, trafficked through countries, beaten and often sold into the Libyan construction industry to pay off their 'debts'.

No-one we spoke to had travelled unimpeded to the Libyan coast. The least malign experience we heard was one young man who described being kidnapped to work as a car mechanic, gaining freedom after five months.

For women, sexual abuse was the norm.

Over on the larger island of Sicily, Mediterranean Hope work with the most vulnerable refugees, offering accommodation and support for unaccompanied minors and women with children.

There's a family feeling at Casa delle Culture - the 'House of Culture' - in the small town of Scicli, pronounced 'Shi-kli'. It is perhaps best known as the main location for the Inspector Montalbano detective series on television.

There's ancient wisdom in those words from Leviticus 19:33-34: "When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them... treat them as your native born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt."

Staff, volunteers and residents eat together. Teenagers sleep on a secure floor with adult supervision. Pregnant girls receive good medical care. Young children attend the church's kindergarten across the road. Art workshops, sport and excursions are organised. Language classes are offered to accelerate the process of integration.

I asked the local Methodist President why the centre had been opened in Scicli, a small nondescript town that wasn't on the coast and several hours away from an airport.

"We accepted the challenge," was his simple answer. When the denomination had received a call after the events of October 3, his congregation didn't know how to decline.

Esther - not her real name - sat down at a table with the group to recount her journey from Nigeria, through Niger, into Libya, to reach Italy.

I was prepared to hear about a hazardous sea crossing. That's that part of the passage that is most frequently recounted in broadcast and print media.

But what caught me off guard was the scale of the serial trafficking and abuse suffered by this orphaned 17-year-old.

The journey to the coast of Libya was a relay race, with Esther the human baton being passed - sold - from one person to another. She showed one scar, on her shoulder, which was the result of a beating. She spoke of three weeks spent with little food.

She was made to 'pay back' twice the amount that she had been bought for in order to be set free by one captor. Attempts were made to extort money from her family back home.

She was shown into a room, given condoms and tissues and assured, "Don't worry, the other girls will help you". Initially reluctant, after six months working as a prostitute she cleared her 'debt' with the help of a local lad and moved on.

Some time later she was raped again by three men. Bought, sold, abused, now a missed period and no access to healthcare, further changed the life of this teenager for ever.

After six months working as a prostitute she cleared her 'debt' with the help of a local lad and moved on. Some time later she was raped again by three men. Bought, sold, abused...

At five months pregnant she finally reached the Libyan coast and after overcoming her fear of "that sea is too big for me to pass" she stepped on board a boat headed to Lampedusa.

Esther's journey from Nigeria to Europe took just over a year. Trying to escape from one captor, she lost contact with her initial travelling companion. Later they would bump into each other near the Libyan coast. Her friend died at sea.

Mediterranean Hope staff confirmed that Esther's story is familiar. In the short term, she will stay in Scicli until she can be placed into a programme that specialises in supporting pregnant girls.

One such initiative is Mediterranean Hope's Centro Diaconale 'La Noce', a four hour drive away in Sicily's capital city of Palermo.

Amongst its multi-faceted social work programmes is one that provides women like Esther with access to health care and language courses, offering safety and security.

It builds the skills and confidence to allow women like Esther to become autonomous and able to live and work independently.

A recent report by the International Organization for Migration described slave markets operating in Libya. This rings true with what our group heard in Lampedusa and Sicily.

Migrants leaving home for Libya have no idea of the horrors ahead. They think they are relying on smugglers when they are more likely to be placed into the hands of traffickers for whom the person is the commodity of value not the journey.

There's an urgent need for more publicity across sub-Saharan Africa about the kind of journey that lies ahead for anyone setting off. No-one we spoke to seemed prepared and forewarned that serial trafficking was the norm, not the exception.

Nationality is often used to determine whether a refugee can remain in Italy to claim asylum or is instead issued with an expulsion order. Not everyone arriving in Lampedusa is now given the opportunity to claim asylum before being sent home.

There is much talk of new financial deals being put in place between the Italian state and African governments, including Libya, that will lead to an increase in the number of deportations by air.

Europe can't wipe its hands clean while it is returning people to the hell from which they have escaped. The brutality we heard about - especially relating to Libya - may mean that the deaths at sea are eclipsed by the deaths due to trafficking.

As we prepared to leave the island of Lampedusa, the team gathered at the Door of Europe monument.

Dom Carmelo joined us for prayer.

Five metres high and three metres wide, elements of the sculpture reflect the journeys made by people wanting to reach Europe in search for a better future.

An open doorway is cut into the artwork. The priest wondered out loud whether a closed door would have better reflected the immigration and asylum policies now in operation.

There's ancient wisdom in those words from Leviticus 19:33-34: "When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them... treat them as your native born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt."

That is a radical and an urgent necessity.

The harrowing tales we heard were tinged with hope. When one of the first women to pass through the Casa delle Culture centre gave birth, the Scicli townspeople took the child to their hearts.

Two years later, little Sara is still recognised on the streets of the town and celebrated; she is their child.

In eight weeks' time Esther is due to give birth. Having heard her story, for the team of guys who travelled to Sicily and Lampedusa, Esther's baby will be our child.

- Alan Meban co-led the delegation to Italy. You can read further reflections from the team on the Focus on Refugees website which he manages for Churches Together in Britain and Ireland.