IT IS interesting to note how at key points in Matthew's Gospel, people often fall asleep or are found sleeping.

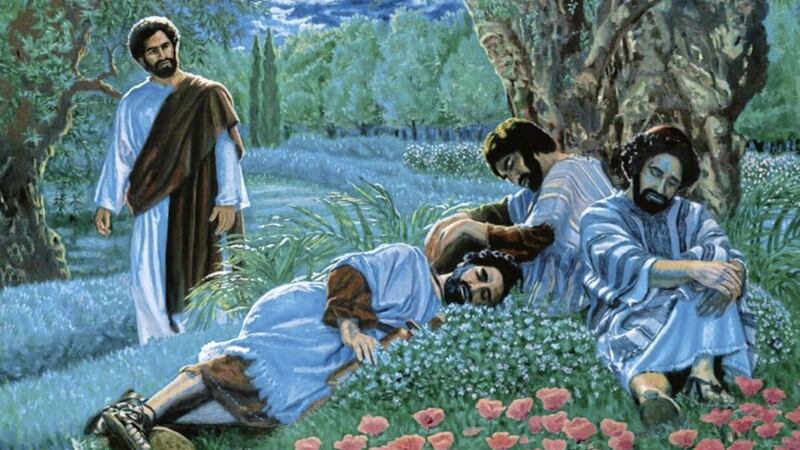

This was the case with the raising of the daughter of Jairus, towards the middle of the gospel, when Jesus said the little girl wasn't dead, but only sleeping. It was also the case with Peter, James, and John, who fell asleep in the Garden of Gethsemane towards the end of the Gospel, while Jesus was going through his `agony in the garden'.

And in the opening chapter of Matthew, which includes an account of Jesus' birth, Joseph is found asleep. In his sleep the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream with the message that Mary, his wife-to-be, was soon about to give birth to a child and the child was to be called Jesus (meaning, God saves).

Maybe these instances of sleeping are just accidental or coincidental and without any further significance. But it's more likely, I think, that they are broad hints about a deep truth that the gospel story is seeking to convey. And that truth is that the salvation God offers the world is a reality greater than anything we could ever effect or bring about by our own conscious efforts, no matter how ingenious or strenuous those efforts might be.

And this is simply because in the grace of redemption God gives us something that is beyond our nature and yet completes it as nothing else can or could. Redemption offers us something `beyond us, yet ourselves', to borrow the paradoxical words of the American poet Wallace Stevens.

Redemption is as far beyond our nature as would be the ability to bring ourselves into existence in the first place or to raise ourselves from the dead, in the last place. And yet the salvation God offers is a reality that can fulfil our nature and delight it, in the way, for instance, that great music, which we ourselves no doubt would be incapable of composing, can still delight our minds and hearts and give us some inkling of the glory for which we've been created.

And looked at from the human point of view, God's salvation, which we alone are incapable of achieving, has perhaps for that very reason the consoling quality of being at the same time a reality that no human failure - no falling asleep on the job, as it were - can ever undermine.

All these considerations may hint at the reason why Matthew concentrates in the account of Jesus' birth on the divine initiative behind the whole reality of Jesus. If we look closely at his account, we'll see that it isn't first and foremost a potentially sentimental story about the actual birth of a little child, though it also speaks about such an imminent event. It's rather a story about the origin or `genesis' (to give the actual term used by Matthew in the opening sentence of his gospel, usually translated `genealogy') of the child. It's a story pointing to the truth underlying and explaining the child's existence.

To use the term `genesis' in relation to Jesus, with its unmistakable reminiscence of the Book of Genesis at the beginning of Scripture, is to lay claim to a link between Jesus' origin and the origin of all creation. For only if the creator of the world is also the reality present and active in Jesus can Jesus be seen as, or be plausibly said to be, the world's saviour, Emmanuel, `God with us'. And interestingly, the notion of God being with us is echoed at the very end of Matthew's Gospel, when Christ promises: "And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age."

In the Christmas season, we're invited to ponder on these unfathomable claims and promises of our faith, and to look forward in hope to their full realization in the kingdom of heaven, when we believe God will be `all in all'.

:: Martin Henry is a former lecturer in theology at St Patrick's College, Maynooth and a priest of the diocese of Down and Connor.