THE fact of betrayal - or at least the tendency to betray - seems to be deeply ingrained in both human nature and in the history of Christianity.

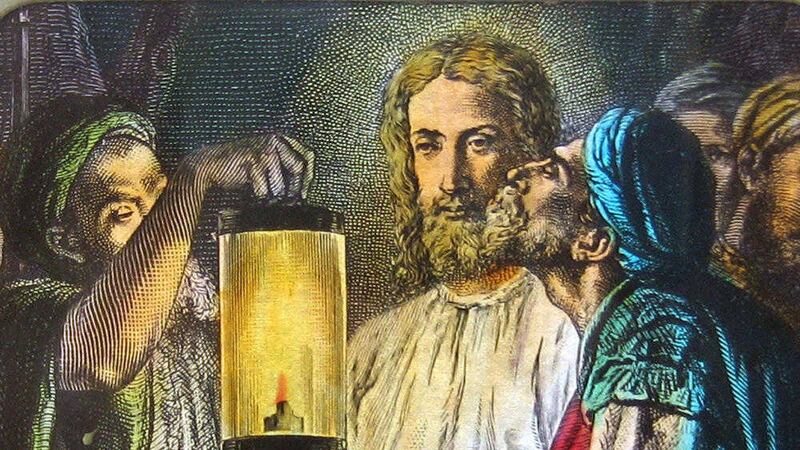

Indeed, the notion of betrayal finds its way even into the traditionally most solemn part of the Mass, the consecration: "On the night he was betrayed..."

There is, of course, little doubt that the dichotomy between the good and the betrayal of the good can be, and has been, exploited for shabby and dishonourable ends within Christian culture itself.

In its long, atavistic history of anti-Semitism, from which it only now may be beginning to emerge, Christianity for centuries almost innocently saw Judas and Jews generally as the embodiment of betrayal.

Judas's betrayal of Jesus has, it would be hard to deny, a much firmer grip on the Christian imagination than, say, the multiple betrayals of Peter, the chief apostle and the first Pope.

Be that as it may, the abuse of a notion should not, on the other hand, entirely discredit its essential validity.

To see the dichotomy between loyalty and betrayal in simplistic terms, attributing them to any two arbitrary groups, is clearly dangerous. But that hardly warrants a refusal to see these two possibilities as latent in everyone.

Putting the matter more vividly, the philosopher Immanuel Kant, who lived between 1724 and 1804, once wrote that human beings were "cut from warped wood", adding that "out of timber so crooked as that from which man is made nothing entirely straight can be constructed" - which is another way of trying to explain what is involved in saying that we are all born with original sin, or that there is something awry in the human scene.

This reveals itself in the way, for instance, no matter how well things ever seem to be going, life has a maddening, almost unerring, habit of going wrong, at least in the short run.

Or, as it was once put, when Adam and Eve bit into the fruit of the tree that was in the middle of the Garden of Eden, providing knowledge of good and evil, they discovered it was sour.

Perfection doesn't seem to be attainable on earth, try though we might to reach or achieve it.

Yet Jesus in his own time certainly appeared to many of his followers to be the incarnation of the perfect life: he gave those who followed him the sense that life was good, and worth living, so much so that many even believed perfection had already arrived, or was about to arrive, in the shape of the Kingdom of God.

But, as we know, Jesus' earthly life didn't lead to the arrival of paradise in this world, but came to an abrupt and cruel end on the Cross, after his intuition that he would be betrayed sadly proved to be true.

And that dark, discordant note of betrayal has sounded throughout all of human history, when one good person or one good cause after another seems to get defeated by what St Paul on one occasion called the "mystery of iniquity", or the mystery of evil.

But if this makes us tend towards a pessimistic view of life, we also have to remember that our Christian faith grew out of Christ's enduring the evil of the world, as its divine victim, but even more so it grew out of his willingness and ability to absorb the pain and suffering of the world, though without endorsing or welcoming it, and, just as significantly, without condemning the world as such for his fate.

In other words, Christ showed there was more to life and more to ultimate reality than an acknowledgement of the fact that suffering and evil are seemingly irremovable aspects of our world. This is what underpins the truth of the resurrection.

A limping truth, it has been said, will always eventually overtake the fastest and the most powerful of lies.

In going to his painful death, Jesus may have abandoned - indeed, he did abandon - his life, but not his faith in God, which was so strong that his followers came to realise that Jesus himself was divine.

The secret of Christianity lies in the fact that although Jesus had a clear awareness of the power of evil, he didn't take from that any message of ultimate defeat or despair; on the contrary, he countered it with a message of love and of faith and of hope and of immortality.

For Jesus believed, and his followers ever since have lived out of this belief, that the reality of God and the reality of goodness is stronger than the forces of evil, and can always eventually outwit, defeat and overcome them.

:: Martin Henry, former lecturer in theology at St Patrick's College, Maynooth, is a priest of the diocese of Down and Connor