MY STOMACH is churning and my heart thumping as I reflect on one of Second World War pilot Douglas Bader's darkest days.

The spirit of my late father is with me as I strap myself into the back of a tiny four-seater Robin aircraft on the very runway that launched the RAF 100 years ago on the outskirts of Saint-Omer in northern France.

We used to share many an enjoyable evening watching reruns of Reach For The Sky, the 1956 black and white biopic of Bader's battle to recover from having both legs amputated when an acrobatic air stunt went tragically wrong, and his journey to become a crack Spitfire fighter pilot.

A short burst of speed and we rumble along the pock-marked Tarmac, past an imposing aircraft hangar built by the Germans after British crews had been forced to give up the site. Then we are up, soaring into cloudless skies on a crisp autumn evening, the sun disappearing over the distant white cliffs of Dover.

Headphones muffle the noisy sound of the single propeller, and our French pilot Francois Mobailly offers reassuring words over the intercom to replace the pounding from my heart.

"It is a beautiful night, oui?" he says, tilting the aircraft to the left so we can take in the beauty of the Audomarois marshes, the spider's web of wetlands that were sculpted by monks in the seventh century.

Then we cross over pretty Saint-Omer, the red tiles of the ancient houses glowing in the fading light that surround its Gothic Notre-Dame Cathedral.

Moments later, Francois breaks into excited chatter. "There it is," he says, nodding ahead and tipping the nose of the aircraft down. "That's where Bader came down. See, down in those fields."

My fellow passengers strain for a view of the patchwork of green fields and golden trees below.

The calmness of the moment gives little hint of the sheer terror Wing Commander Bader must have been feeling that bleak August day back in 1941.

Already handicapped by the loss of both legs, Bader was forced to bail out of his stricken Spitfire after being caught in crossfire during a fierce dogfight with German Messerschmitt Bf 109s.

He struggled to release one of his artificial legs from the cockpit and had to leave it in situ before the aircraft plunged to the ground. He was able to release his parachute just in time, but the impact when his remaining prosthetic leg hit the ground caused such damage that he was knocked unconscious and very nearly died.

His story of recovery in a Luftwaffe hospital, escape using tied bedsheets from the top floor of the hospital to a Saint-Omer safe house, rearrest and eventual incarceration at the notorious Colditz Castle in Germany, is scarcely believable.

It prompted the good folk of Saint-Omer to launch The Douglas Bader Trail, a fascinating two-hour trip down memory lane, laced with anecdotes and visits to the most significant venues featured in his life.

My prized possession as a boy was an autograph book featuring Douglas Bader's signature, which my father helped secure as a press photographer in the 60s, so the chance to tag along on the tour was too good to miss.

It also affords me an opportunity to see some of the jaw-dropping remnants of the Second World War that lie on the outskirts of the town, and to visit some of the immaculate war cemeteries in honour of my late great uncle Wesley, who is buried nearby after falling in the First World War at the age of 19.

Saint-Omer is easily reached in a little over an hour-and-a-half from London by train and car via the Eurostar.

First stop is the aerodrome at Longuenesse on the outskirts of the town, which gave birth to the RAF when the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service merged on April 1, 1918, making it the oldest independent air force in the world.

There was much pomp and ceremony here to mark the 100th anniversary earlier this year, acknowledging the role the airfield played in hosting more than 50 RAF squadrons over the years. It also provided a base for the Luftwaffe to launch attacks on London during the Battle of Britain after France had been invaded.

Now, only a stone memorial, built in the shape of a hangar and carrying the RAF slogan, 'Per ardua ad astra' – 'Through adversity to the stars' – remains, although plenty of old pictures adorn the Aeroclub de Saint-Omer clubhouse.

The RAF's motto could have been written specifically for Bader, whose iron will and bloody-mindedness made him such an inspiration to injured pilots and the disabled at large.

"Don't listen to anyone who tells you that you can't do this or that," he once said. "Make up your mind you'll never use crutches or a stick, then have a go at everything. Never let them persuade you that things are too difficult or impossible."

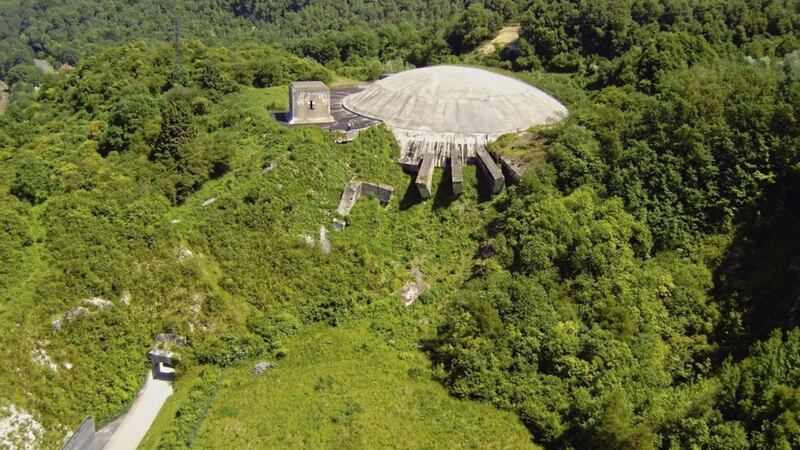

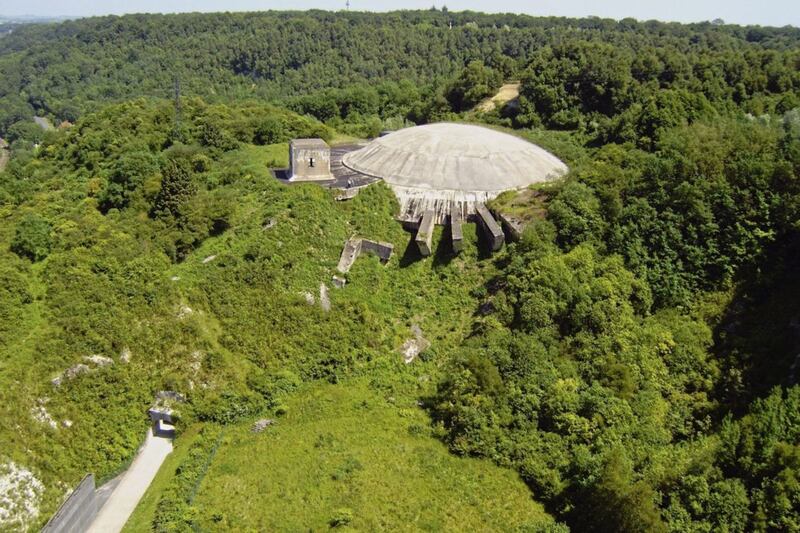

An exhibition of the RAF's work in France during the two world wars, including a special tribute to Bader, can be found close by at La Coupole (The Dome), one of the most impressive bunker remnants in Europe, where the Nazis planned to launch dozens of V2 rocket-propelled bombs a day.

Walking through its maze of dark and foreboding tunnels feels like being on the set of a James Bond movie. I can just picture gadgets expert Q explaining to Bond how he could use one of his devices to stop the 46ft 15-ton V2 bombs from raining on London.

In fact, it was a ground-penetrating 12,000lb tallboy bomb that brought the project to an end just weeks before it was due to go fully operational. The bomb fell on the fringes of the bunker, causing so much structural damage to the walls and entrances that the bunker had to be abandoned. Without it, the course of history could have changed, although the rockets at least provided scientists with the tools to make space travel possible in later years.

A similar fate met the nearby Blockhaus d'Eperlecques, the so-called Watten bunker, which is arguably even more impressive in its size and capacity to bring destruction through V2 bombs, Adolf Hitler's Wunderwaffe (wonder weapon). Now part of a privately owned museum, the site boasts a trove of wartime artefacts with fascinating historical narratives.

It gives my party plenty to reflect on over a hearty meal of chicken, cheese sauce and fresh vegetables at the small, quirky and yet highly recommended Chez Tante Fauvette restaurant in the shadow of the Cathedral of Saint-Omer.

A three-day helping of war stories and memorabilia may not appeal to everyone's taste, but in such a volatile world, we owe it to likes of Bader, my great uncle and many more to look and learn. Chances are, the experience will live long in the memory.

FACT FILE

:: Eurostar (eurostar.com/uk) offers fares from St Pancras International to Calais-Frethun from €33 (£29) one way.

:: Rooms at the Najeti Hotel du Golf (golf.najeti.fr/en) cost from €88 (£78).

:: Pleasure flights for two from Saint-Omer airfield cost from €81 (£71) Visit acsto.fr.

:: The Douglas Bader tour is €8 (£7). Book through mannedup.com.

:: Entry to La Couple and Blackhaus d'Eperlecques (lacoupole-france.co.uk) is €10 (£8.80).

:: For more information, visit tourisme-saintomer.com