I PREFACED my Easter Rising trip to Dublin with a bit of The Wolf Tones, specifically the touching song Grace, imagining Joseph Plunkett's thoughts about love and loss as he awaits his fate in Kilmainham.

As the chorus has it: "Oh Grace just hold me in your arms,and let this moment linger,/They take me out at dawn and I will die,/ With all my love I place this wedding ring upon your finger,/ There won't be time to share our love so we must say goodbye."

On the final day of our whistle-stop tour of Rising sites, my husband Michael and I stood feet from the spot in the prison chapel where the already ill Plunkett married the artist Grace GIfford.

This was an extremely moving moment among many in a weekend that sparked admiration for the spunk of the Easter Rising leaders, so hideously outnumbered in their struggle with the British forces, and some sadness that it didn't come off.

We began with one of the most entertaining (and informative) history tours I've been on. Hopping on a converted school bus, now the 1916 khaki truck operated by Freedom Tours, we stepped back 100 years.

Ken Harrington, kitted out in British army khaki for the occasion, proved to be the kind of tour guide you don't forget. He not only narrated the story, counting out the bullet holes for us all round the city centre (including in the winged females flanking Parnell's monument), he took us back to the people and personalities.

For example, Nurse Elizabeth O' Farrell, his favourite female combatant in the Rising, as he told us. She was a dispatch rider and in the midst of the action at the GPO until the end.

We wound our way through a city fighting for freedom, and survival. Past Dublin Castle where the first casualty was killed, a postman. Past St Stephen's Green where Constance Markiewicz and her men dug trenches which tragically enabled the English soldiers posted in the buildings round about to pick them off easily from superior height. Past the area where De Valera made a foxhole and managed to sit out, and get some targets, through the conflict. Past the terraces where ordinary folk who weren't involved had to spend days indoors.

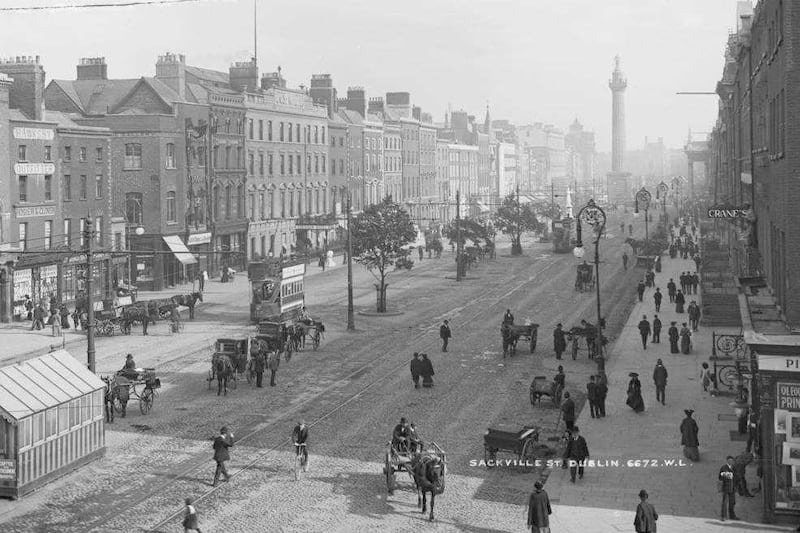

Period photos were beamed on to a small screen at the front and the lively narrative given us by Harrington, a natural performer who has written a play about his heroine, was not always comfortable listening for someone from England. But hey, my mother's maiden name was Riley so maybe I am lucky enough to have some green in the genes.

Most surprising fact? I knew De Valera's garrison had no women fighters as he felt they shouldn't take on military roles (which they courageously did elsewhere in the city) but did not realise how the odds were stacked against the putative revolution. 1,600 Rebels were dealt with by a cohort of 20,000 well-armed British. At one fighting position, the leaders knew they needed 1,000 men to have a chance; in the end, 160 turned up, and seven left the first night. You can understand why.

Also fascinating was the historical footnote that De Valera was spared because someone told the British high-ups he wasn't important, only a teacher. How wrong can you be. Also, Markiewicz was spared not only because of her gender but because the British wanted to distance themselves from the German killing of Edith Cavell.

The National Museum, in its outpost at Collins Barracks, provides brilliant context.

On Saturday night, the husband and I headed for a superb meal to Bang restaurant. Over the risotto with truffle shavings and lamb and duck leg, we discussed what we'd seen.

This is a good celebrity haunt and at the next table sat Jeffrey Archer. I interviewed him a couple of times back in the day so we chatted for a bit about British politics, Boris Johnson and Europe.

In a way the European discussion was relevant. The Republic is now an outward-looking, euro-deploying, modern state. And in the GPO building's new visitor experience about the Rising, I saw quotes from the likes of Lenin and Churchill, commenting on the events of Easter 1916.

So on Sunday morning I headed for the GPO building, where things really kicked off, for an exclusive preview for The Irish News. And worth seeing. This brand new witness history experience, now a permanent fixture in the building where the magnificent Proclamation was first read out, was also the locale where Pearse and co held out for an incredible six days.

The exhibition charts the whole Rising and provides fascinating background. There are historians doing what they do best on video, there is an audio visual film called Fire and Steel, and there are touching artefacts which transport you to that febrile era. I loved the dispatch bikes, used by postal workers trying to maintain communication with London against the best efforts of the rebels.

There was even a computer game, which I also loved, where you try to steer your green (of course) bike through burning Dublin while avoiding the British military. Needless to say, I was "killed" several times.

One of the pictures in the well-thought-out background folders, where you touch the bit you want and a bristling text appears, was of a small boy in the Dublin street and he wasn't wearing shoes, just a bandage on one foot.

In the courtyard, there's a modern sculpture with 40 small rocks representing the number of children who died in the Rising. There is also a memorial list of the adults who perished, 318 in total.

I felt rather guilty at staying in comfort when nearby St Stephen's Green was a bloodbath a century ago. And crossing the Green, with its bust of Markiewicz and its Celtic motifs, gives you another sense of what 1916 was all about.

But if you do visit the city where it all happened, and you really should, The Dean Hotel in Harcourt Street is a good choice. Boutique, quirky and with great customer service, it has a fifth-floor restaurant that thinks it's a diner where I had the best rotisserie and frites I've eaten since last in Paris. The other half loved his steak.

One tiny word of warning: this is hipster central (apparently Benedict Cumberbatch has stayed here a couple of times) and boasts great bedrooms and customer service but at night, the DJ sets feature some pretty loud house music. Use those ear plugs.

While this was a chastening weekend, it was enlightening too. But we ended, as we had to, with Kilmainham Gaol where the Rebellion leaders apart from Dev, also ended their struggle.

We saw the spot where James Connolly was shot while strapped to a chair. We heard about the sandbags positioned behind the prisoners, presumably to absorb any blood. We spent a minute thinking, admiring and wondering.