ONE of the more memorable quotes I heard this year is that Boris Johnson’s Brexit deal is like an onion - the more layers you pull off, the more it makes your eyes water.

The comment was from Manufacturing NI’s Stephen Kelly during a review of the year podcast discussion we held at Ulster Bank. And in many ways, the same simile could be used to describe 2020. I think the more people get into the year, the more they’ll realise how much uncertainty there still is and the more their eyes will water.

Many had hoped that with the December election over and a decisive result being the outcome that there would at least be more certainty in 2020. Boris Johnson’s 'Get Brexit Done' strapline certainly helped create the impression that his success in the election will now see Brexit and the uncertainty that has gone with it put to bed. Think again.

The World Uncertainty Index peaked in Q2 2019 due to ongoing Brexit indecision and the trade wars between the US and China. The reality is though that whilst uncertainty has eased back from its recent highs, the World Uncertainty Index (Source: Ahir, H, N Bloom and D Furceri 2018) is expected to remain elevated during 2020, with no shortage of uncertainty economically, politically and otherwise.

In the UK, whilst Boris Johnson has received a strong mandate for his Brexit deal through the election result, and his deal will therefore likely be voted through, that will actually only be the beginning of a process rather than the end. Still a huge amount is to be negotiated with the EU around the future arrangements. In reality the UK economy is also likely to deteriorate in the months ahead.

Indeed, this is something that Boris Johnson was mindful of in calling the first December election in decades. And he knew that having an election at a later stage would not be to his advantage when the economy would be in a weakened state.

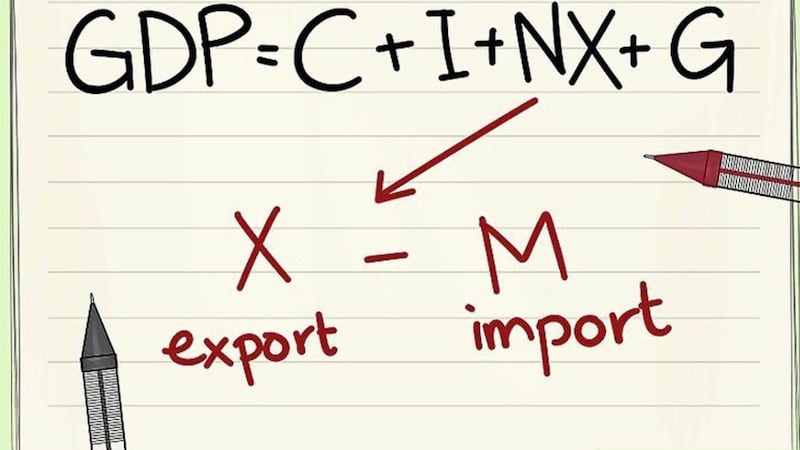

In terms of making predictions about economic growth in 2020, my answer is C+I+G+(X-M) = GDP.

For those in the know, that’s an equation economists use to determine economic output. But this year with the level of uncertainty there has been, it just hasn’t been overly credible to make those kind of predictions.

But although uncertainty will reign in 2020, with the election passed, I feel a bit more confident filling out some of the components of the equation. For clarity, C represents consumer spending; I is business investment; G is government spending; X-M is exports minus imports, or net trade. And perhaps the two biggest elements to consider for 2020 are I and G.

Looking at I first, the level of business investment in the UK is only fractionally higher now than it was whenever the EU Referendum was called in June 2016, with investment increasing in only one of the last seven quarters, which is something the UK has never seen before. (By comparison, business investment rose by one-fifth in the three years before the referendum).

The fact is if you aren’t investing now, you don’t get economic growth in the future, and as businesses haven’t been investing over the past three years, this will impact on the growth prospects of 2020 and beyond.

Northern Ireland is no different in this respect; indeed the situation is arguably even worse given the exposure to Brexit uncertainty here has been even more acute. The most recent figures for housing starts in Northern Ireland show that 2018 was the highwater mark for house building and that 2019 has seen investment in new homes fall back. And this trend is almost certain to continue.

In terms of G, many people have been pinning their hopes on government spending to give the economy a boost. And indeed, we have already had a boost to spending announced a few months ago which is yet to feed through into the economy.

Looking ahead, whilst commitments to spending in the Tory election manifesto were modest, my view is that the PM will want to assuage discontented working-class constituencies that have put their faith in the Conservative Party by giving them an injection of funding. We await February’s UK Budget with interest.

However, it should be remembered that whilst the age of austerity is over and government spending will rise, we are definitely not going back to pre-austerity spending levels. Much of the new spending will have to go towards back-filling fiscal potholes (and craters) rather than driving the economy forward. The public spending Nirvana that Corbynistas dreamed of vanished into the 12th December night.

And in Northern Ireland, with no Executive nor Assembly in place, there is currently no political direction to help ensure the spending is directed towards areas that will most benefit the economy. Northern Ireland’s special-pleading for public spending is also likely to increasingly fall on deaf ears in the new political reality in London.

The reality is there are English constituencies that have recently switched from backing Labour to Conservative that are more deprived than those in Northern Ireland.

One example is Redcar, the former constituency of Mo Mowlam. The PM has a greater political imperative to help these areas.

While the shape of UK politics and public spending will be clearer in 2020 there remain other sources of uncertainty. The rules of the game as far as global trade are concerned are in a state of flux. What with the ongoing trade wars between the US and China.

More crucially, the trading relationship with our largest market – the EU – is up for negotiation. Lack of clarity on this front will impact on both net trade (X-M), firms’ investment plans (I) and ultimately on jobs (and ‘C’ consumer spending) for the foreseeable future.

Those who know their onions will be prepared for anemic economic growth for some time yet.