THE financial crisis of 2008 still haunts investors, sometimes to the extent of making the avoidance of large losses their primary objective. This caution is heightened when taking the initial plunge: surely it pays to wait for a good entry point?

The problem with this approach is that one can all too easily end up perennially perched on the sidelines, waiting for a moment that will never come. All the while, stock markets may climb ever higher.

To see just how much can be forfeit, let’s consider a basic investment strategy of waiting for prices to fall by a certain amount before putting up the cash. For example, let’s suppose that five years ago, in May 2012, we decided to invest as soon as the end-of-month value of the FTSE 100 recorded a decline from its maximum – a “drawdown” – of 10 per cent.

Such a drop would not have been seen until August 2015 – a wait of over three years. By that time, even after the fall, the total return (including dividends) since May 2012 would have been 23 per cent. It would have been better just to invest from day one.

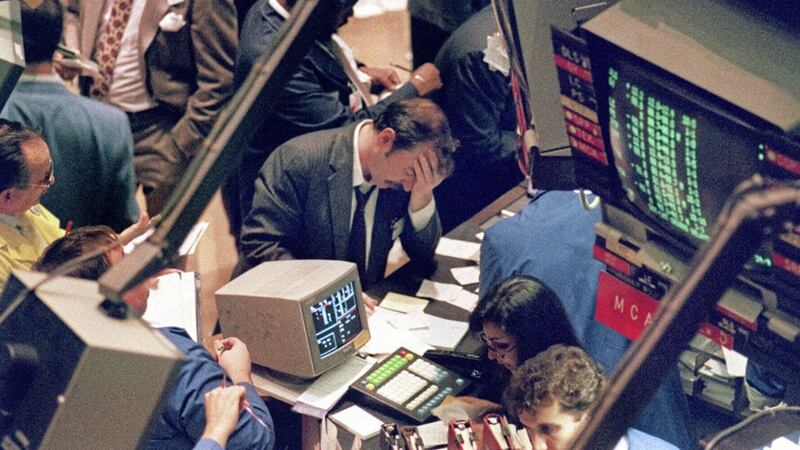

At the extreme, the forfeit can be immense: a hypothetical investor who waited from August 1982 for a 10 per cent draw down in the price of the MSCI World index would have sat in increasing despair as they watched stocks triple in value even after Black Monday eventually came along in October 1987.

Looking at all the potential starting months of this “wait for a 10 per cent price draw down” strategy back as far as the MSCI World index will go (1970), we see a succession of long periods of very large forfeit total returns, punctuated by times when waiting for a sell-off has indeed dodged a pullback.

Overall, the median forfeit total return is 15.5 per cent; the mean 28.9 per cent; the probability of losing out 68.3 per cent. But even at those serendipitous moments when caution is flattered by the look of prescience, the strategy is predicated on the ability to invest in the midst of market ructions and panicked headlines. If the aim is to avoid short term losses, a plan to jump headlong into a still-deepening abyss would be an odd way to go about it.

One might argue that waiting for a drawdown before investing would only be sensible if stock markets are reaching new highs. Does the “wait and see” approach fare any better if we restrict our analysis to those occasions when prices hit asphyxiate altitudes?

Not much. Returning to our example of delaying prospective investment until the MSCI World records a draw down of 10 per cent, but this time only if prices are at the highest they have been for the past year, the picture is still a gloomy one – the median forfeit total return is 12.6 per cent; the mean 25.6 per cent; the probability of losing out 72.1 per cent. Looking at local highs over longer horizons seems to lessen the loss, but never reverses the situation; the same is true regardless of drawdown threshold.

In the short term, stock markets are almost as likely to post losses as they are to make gains. It is therefore always tempting to try to “buy low, sell high” by waiting for a decidedly low entry point.

But in reality, it is difficult both to identify and to act on these moments. Instead, would-be investors lacking both a time machine and the awfully well-rewarded ability to predict the stock market would be better served by aiming to “buy now, sell later – much later”.

:: Jonathan Dobbin (jonathan.dobbin@barclays.com) is head of wealth and investment management NI at Barclays. He can be contacted on 028 9088 2925.