THE IRA's Northern Offensive of May 1922 was the last desperate attempt by an increasingly divided IRA to end partition through military means at the time of the establishment of Northern Ireland.

Almost from the start, it proved a disastrous failure that resulted in the collapse of the Northern IRA which was thereafter unable to make a serious attempt to challenge the northern jurisdiction for the next 50 years.

The main driver behind the offensive was Michael Collins, the chairman of the Free State provisional government. His main motive in calling for the attack was arguably to unite the IRA and stave off a civil war in the Free State instead of a sincere effort to aid the beleaguered northern Catholic minority. By starting a war in the north, he could avert one in the south.

With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and the subsequent formation of the Free State provisional government under Collins the following month, he became the effective voice of the minority community in the north.

His strategies on the north right up to this death in August 1922 were bizarre, contradictory and counter-productive. On the one hand he pursued political and passive opposition tactics and on the other he sought to militarily destabilise the north, with an ultimate aim of ending partition.

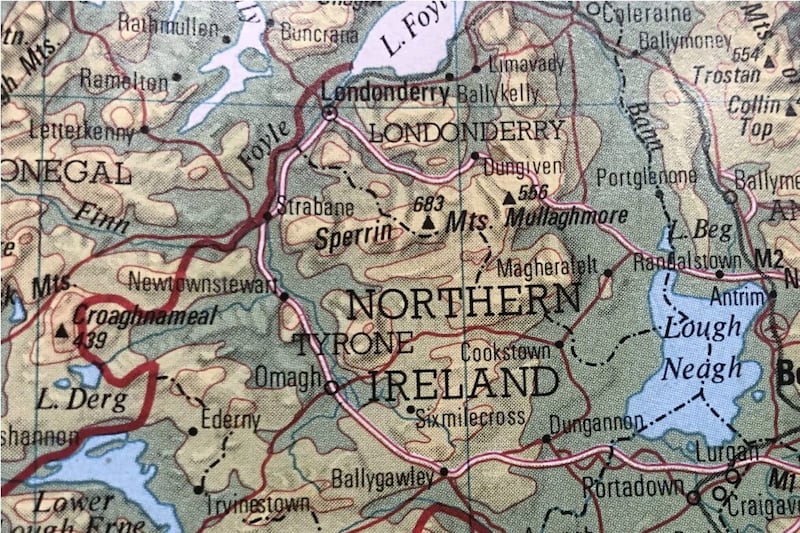

Collins established an 'Ulster Council' in early January 1922 to coordinate IRA activity in the six counties and along the border which included all of the commanders of the five Northern Divisions. He also established the Belfast City Guard to comprise of men from the Belfast IRA Brigade to run all IRA operations in Belfast during 1922.

These bodies were responsible for attacks on loyalist and northern government personnel and property as well as providing defence to the Catholic community, something they were clearly unable to do, judging by the relentless attacks on Catholics from loyalist mobs, Specials and RIC members in Belfast in the first half of 1922.

Frustrated at political and propaganda efforts to reach a solution on the north in the first three months of 1922, Collins opted for an exclusively military solution. Such a solution could also be the one area where unity could be achieved within the IRA, horribly split and fractured since the signing of the Treaty and hurtling quickly towards a civil war.

A shared crusade of an offensive to end partition, it was hoped, could outweigh Treaty divisions and prevent civil war in the Free State. The plight of the Catholic minority in the north, particularly in Belfast, did much to unite the IRA with pragmatic and idealistic, pro- and anti-Treaty members open to purely military solutions to the Northern issue.

An ambitious plan was hatched from March for a May offensive involving all the Northern Divisions and both pro- and anti-Treaty factions in the south to, in the words of Belfast IRA leader Roger McCorley, bring about the "downfall of the six-county government by military means".

On paper, at least, a full-scale invasion of the north was planned. According to Robert Lynch in his book The Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition, 1920-1922, "While the pro-Treaty side would be largely responsible for supplying the arms and equipment, the anti-Treaty IRA would provide the leadership. It was left to the Northern IRA to supply the majority of the actual manpower to carry out the attacks."

Thousands of rifles, machine guns, grenades, land mines, detonators and boxes of ammunition were sent over the border and distributed throughout the six counties. Collins, seeking to hide his and the provisional government's involvement in the offensive, could not ship weapons the National Army had received from the British to the Northern Divisions. Instead, he swapped weapons, supplying anti-Treaty IRA weapons to the Northern Divisions, and giving the anti-Treaty IRA the British weapons in return. Some weapons arrived as planned. Others did not, undermining the fragile trust that was there in the first place.

The new 'Army of the North' planned to spearhead attacks on the northern jurisdiction from within and outside the border. The remote chance the offensive had of succeeding was dependent on disciplined coordinated attacks from a number of different fronts to stretch the vastly superior enemy forces.

The opposite happened. The planned start date for the offensive of May 2 was called off, postponed first until May 5 and then until May 19. Even though the dates were rescheduled, the 2nd Northern based in Donegal was unable to postpone its plans and was permitted to proceed on May 2. The cancellations coupled with the permission to allow the 2nd Northern to proceed proved disastrous, allowing the northern authorities to pick off individual divisions with relative ease. Instead of uniting behind a common enemy, open hostility broke out in Donegal between the pro- and anti-Treaty IRA factions, with four pro-Treaty soldiers killed by anti-Treaty IRA members in Newtowncunningham on May 4.

Once the unity between both sides waned, Collins's commitment to the offensive also faded. The three Free State-based pro-Treaty divisions (1st and 5th Northern, and 1st Midland) were told to hold back from travelling north. The 4th Northern under Frank Aiken also cancelled its planned operations.

Like sacrificial lambs, the 2nd and 3rd Northern Divisions proceeded with the offensive and were allowed to do so. Some noted the similarities with Eoin MacNeill's countermanding order six years previously, on Easter Sunday 1916. The 2nd Northern began their offensive as arranged on May 2 with attacks on police barracks at Bellaghy, Draperstown and Coalisland, with little effect.

By the time the 3rd Northern began its offensive in Belfast in mid-May, the IRA in the west of the six counties had already virtually collapsed.

The 3rd Northern began its operations on May 18 with an audacious attack on Musgrave Street Barracks in Belfast where the Belfast City Guard planned to capture eight Lancia cars and four armoured cars along with weaponry. They gained access to the barracks but when the guards there called for help the IRA were forced to flee the scene without capturing anything.

They still began widespread operations the next day, but like the 2nd Northern, were isolated and exposed and were soon overwhelmed by the vastly superior loyalist numbers. Belfast was engulfed in dozens of serious fires; railway stations and mills were destroyed.

With the Belfast IRA feeling isolated and alone, demoralisation was rampant as were attacks from enemy forces. Trainloads of Specials were able to converge on Belfast due to the inactivity of the IRA elsewhere. The offensive in the rest of Antrim also petered out quickly once Specials arrived in large numbers, with many IRA members dumping their arms and fleeing.

One of the last incidents of the offensive occurred at the Pettigo-Belleek salient on the Donegal-Fermanagh border, when a week-long stand-off between IRA forces and Specials saw the intervention of British Army troops in early June who used artillery in Ireland for the first time since the 1916 Rising to repel the IRA forces.

This prompted the Free State provisional government to declare on June 3, "that a policy of peaceful obstruction should be adopted towards the British Government, and that no troops from the twenty-six counties, either official or attached to the (anti-Treaty) executive should be permitted to invade the Six County area."

This was mere confirmation that the Northern IRA was on its own, abandoned by the south, something clear to most since the start of the offensive. With the outbreak of the civil war in the Free State and after the severe clampdown by the northern government on the IRA and Catholic civilians after the assassination of the Ulster Unionist MP WJ Twaddell on May 22, the Northern IRA was forced into its long retreat, defeated and demoralised.

::Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).