EXACTLY 100 years ago today, on March 30 1922, the second of the so-called Craig-Collins Pacts was signed in London by representatives of the British, Northern Irish and Irish Free State Provisional governments.

The driving force behind both pacts (in January and March 1922), Winston Churchill, later that evening in the House of Commons, grossly exaggerated the outcome by announcing that, "Peace is today declared".

Given the failure of the first pact in January to get off the ground and the intense violence that had engulfed the north, particularly in Belfast, in the intervening period, he was clearly being a hostage to fortune in hoping the latest agreement would fare better.

It didn't - in tatters almost as soon as the ink on it was dry. Lord Hugh Cecil, a diehard Tory, was more accurate in describing the pact as "a statue of snow".

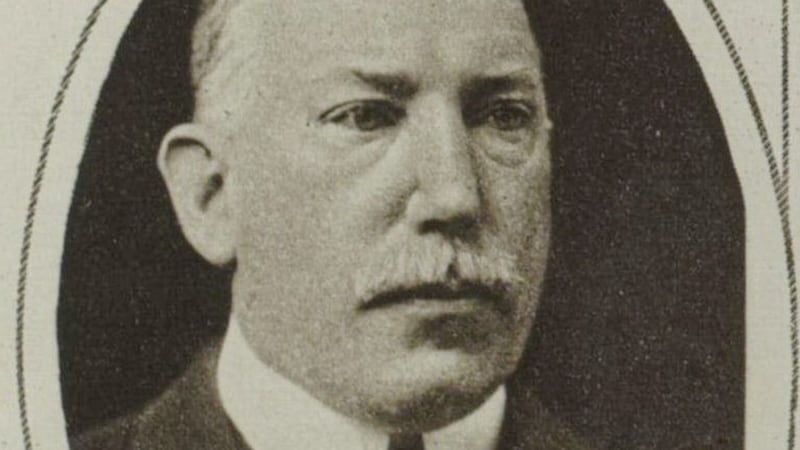

Churchill brought Northern Ireland prime minister James Craig and Irish Free State Provisional government chairman Michael Collins together in London on January 21, fearing that the northern question posed great threats to the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed the previous month.

He also believed in the merit of direct discussions between both leaders. He was surprised and satisfied when both Craig and Collins agreed to be left alone, on Craig's suggestion, and produced an immediate draft agreement.

Collins agreed to discontinue the Belfast Boycott (begun in August 1920 in protest against the removal of Catholic workers from Belfast shipyards) while Craig promised to facilitate, "as far as economic conditions allowed", the return of expelled Catholic shipyard workers to their jobs.

The Belfast Boycott was discontinued (until the anti-Treaty IRA reinstated it again) but Craig failed to secure the return of many Catholics; just 20 Catholics out of over 7,000 were re-instated in the shipyards by the end of January.

A large-scale system of relief was sought from the British government to deal with unemployment in the north, and both endeavoured to find a more suitable system than the council of Ireland for dealing with problems affecting all Ireland.

At the meeting, Craig told Collins that an "All-Ireland Parliament was out of the question, possibly in years to come – 10, 20 or 50 years – Ulster might be tempted to join with the south", and wanted to know if it was Collins's "intention to have peace in Ireland or whether we were to go on with murder and strife, rivalry and boycott and unrest in Northern Ireland".

According to Craig, Collins "made it clear that he wanted a real peace and that he had so many troubles in Southern Ireland, that he was prepared to establish cordial relations with Northern Ireland, to abandon all attempts to coercion, but hoping to coax her into a union later".

Collins, showing a less than wholehearted commitment to the boundary commission he had been promoting weeks earlier, agreed with Craig for them to deal with the question of the boundaries without help or interference from any British authority, and to nominate representatives reporting to Collins and Craig directly with a view to "mutually agree" borders.

Their agreement on the boundary was even more vague than Article 12 of the Treaty. The main conclusion Collins drew from the conference - a wholly naïve conclusion - had "been that north and south will settle outstanding differences between themselves. We have eliminated the English interference".

The pact was broken within days over unrealistic expectations and a significant escalation of violence in the north. Although broken, the pact was still noteworthy in some respects.

Collins was now considered the spokesperson for northern nationalists, at least by the British. And whilst Craig claimed the pact showed that the provisional government accepted partition and the legitimacy of the Belfast government, his agreeing to the meetings involved in some sense a recognition that the Dublin government had some say over what occurred north of the border.

The months after the first pact saw the violence reach new levels of brutality. It was a civil war in the north in all but name. Churchill was Secretary of State for the Colonies, the British cabinet minister responsible for Ireland.

After the vicious 'McMahon Murders' on March 24, when six males were killed in their house (five from the one family) by men in police uniforms, Churchill urged Collins and Craig to meet again, resulting in a conference in London on March 29 and 30.

The second pact had more concrete proposals. It was agreed "to reform the Belfast special constabulary and to recruit Catholics into that force".

Once IRA activities ceased in the six counties, special constabulary reforms would extend beyond Belfast. The British government committed to supplying "a relief grant, not exceeding £500,000" to Northern Ireland.

The northern government again promised to help to restore employment to Catholic shipyard workers and both sides agreed to commence prison releases.

Despite the euphoria it was greeted with in some quarters, others like the Irish News were more sceptical, writing: "The statement reads like an unexpected avowal that a miracle has been performed - there are thousands who will think this morning that the news is too good to be true."

The scepticism was justified. The agreement broke down almost from the outset, unsurprising given the circumstances, obstacles and nature of the pacts.

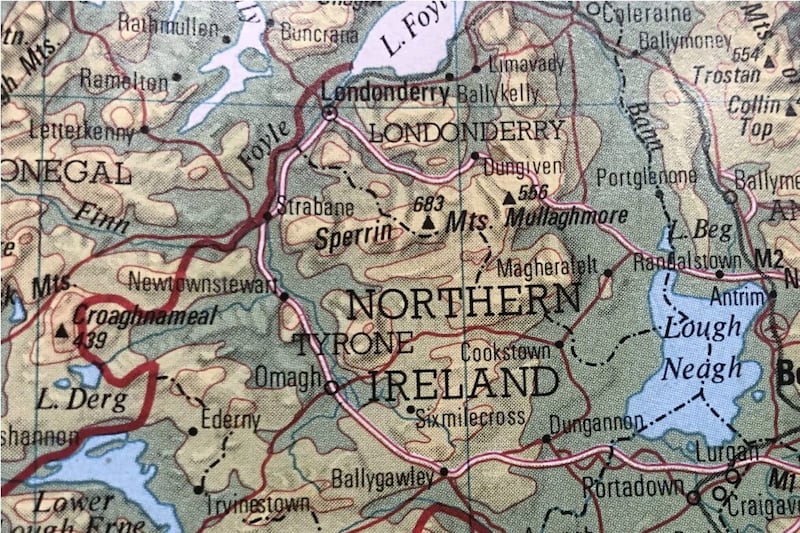

Firstly, the pacts were always unlikely to work given that they merely dealt with the symptoms of the problem and not the causes. No attempt was made to come to terms with the highly contested border issue nor with northern Catholics' reluctance to recognise the Northern Ireland government.

The attempts to get Catholics to join the Specials was always unrealistic. Catholics would risk being shunned from their own community if they did join a force known for its deep-rooted sectarianism.

Secondly, neither the northern nor the provisional governments were committed to the pacts from the outset. It appears Churchill was the sole cheerleader, even still doing so after the civil war had begun in the south in the summer.

Craig, initially less of a diehard than some of his colleagues, increasingly followed their lead. He claimed the pacts had resulted in Sinn Féin making all the concessions. He made no effort to commit to any of the clauses around policing, conciliation nor Catholic employment rights he agreed to in the pacts.

The pacts, for Collins, were in many ways a public front, who, by his other actions, sought to destabilise the northern jurisdiction. On top of arming the IRA for engagements in the north, Collins led a policy of non-recognition of the six counties, which caused deep frustration for the British and Northern Irish governments.

One of the primary policies of non-recognition involved the payment of salaries of Catholic teachers based in Northern Ireland who refused to recognise the six counties' ministry of education.

The drive to improve the lot of Catholics in the north, through the pacts, came from nationalist MP Joe Devlin and northern Catholic businessmen who supported him, not from the provisional government.

Churchill later claimed to regret in making Collins spokesman for the minority population, saying to northern Catholic businessmen, "the thrusting aside of Mr Devlin had been one of the worst disasters in the situation".

The timing of the pacts also contributed to their downfall, coming at a time when the provisional government was trying to stave off a civil war in the 26 counties, when Ulster unionist paranoia and insecurity was at its zenith due to the Treaty provision for a boundary commission, and when the scale of the violence in Belfast was at its most fierce during that period, making it extremely difficult for compromises to be entertained. In such an environment, the pacts stood little chance of succeeding.

::Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).