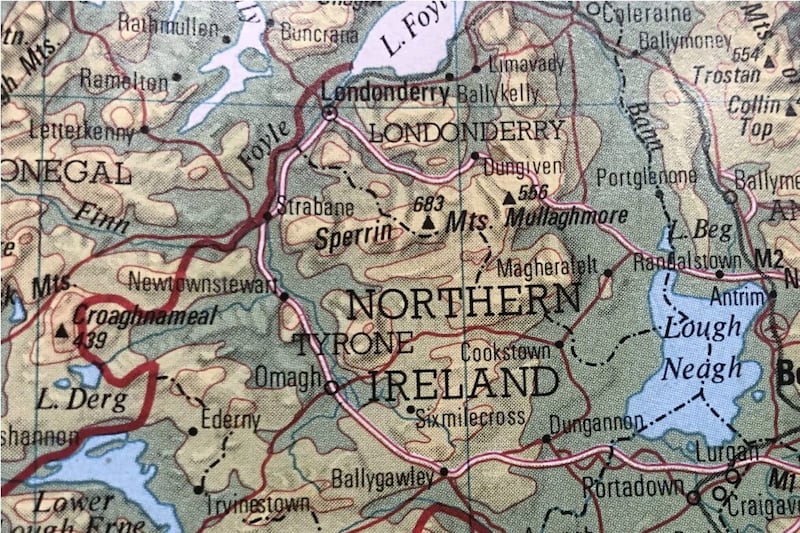

ON November 28 1921 the nationalist-controlled Tyrone County Council voted to recognise Dáil Éireann and to ignore the Local Government Board which was in the process of being transferred to the Northern Ireland government's Ministry of Home Affairs.

Smaller public bodies followed suit and the other nationalist-controlled county council in the six counties, Fermanagh, also pledged allegiance to the Dáil in December 1921.

The move by the county councils was not unprecedented as most of nationalist Ireland had embarked on a policy of non-recognition of Northern Ireland and its institutions the moment the Government of Ireland Bill was introduced in late 1919, which paved the way for the partition of Ireland.

Sinn Féin and Joseph Devlin's United Irish League fought the first election to the Northern Ireland parliament in May 1921 on an anti-partition abstentionist stance.

This was a continuation of Sinn Féin's policy of ignoring British institutions, creating its own counter-state, and conducting a boycott on northern-based businesses.

Both parties, who won six seats each, refused to take their seats in the Northern Ireland House of Commons. Some claimed they helped to legitimise partition by contesting the election in the first place.

As the lower house appointed members to the Northern Ireland Senate, no nationalists were represented there either. Unionists held a monopoly over parliamentary proceedings as a result.

The Catholic Church also adopted a non-recognition policy with the onset of partition. Invited to the official opening of the Northern Ireland parliament by King George V on June 22 1921, the Catholic Primate of Ireland, Cardinal Michael Logue, turned down the invitation, claiming he had a "prior engagement".

Instead, he, along with the rest of the Catholic hierarchy, condemned the new parliament, calling it a "sham settlement devised by the British Government".

Logue also refused to participate in the Lynn Committee in September 1921, named after its chairman Robert Lynn, to propose structures for the future of education in Northern Ireland. Offered four out of 30 seats on the committee, Logue explained the reasons for the Catholic Church's non-participation, saying, "I have little doubt that an attack is being organised against our schools".

Nationalists in Northern Ireland were supported in their strategy of ignoring and boycotting northern institutions by the national leaders of Sinn Féin. The Dáil Minister for Local Government, W.T. Cosgrave, sought for northern-based public bodies to declare allegiance to the Dáil as a means to emphasis the level of opposition to the Belfast parliament while the negotiations between the British government and Sinn Féin were taking place in London.

On December 7 1921, the day after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a delegation of northern nationalists travelled to Dublin to meet with the Speaker of the Dáil, Antrim-native Eoin MacNeill, who urged them to adopt "a practical programme of passive resistance" towards the northern government's authority, to include the non-recognition of the courts, non-payment of taxes and particularly the non-recognition of the educational authority of the northern government.

Division and lack of consensus did not help nationalism's attempts to successfully oppose Northern Ireland institutions. The establishment of Northern Ireland and its institutions posed a dilemma for nationalists who were incredulous that such a 'solution' was imposed on them without any consultation.

Even though many felt it was a temporary arrangement, the longer Northern Ireland existed and the more powers it received, the more nationalists were forced to choose between a policy of continuing to ignore its existence or using its institutions for the betterment of nationalists within Northern Ireland.

Recognising its institutions could be seen as legitimising Northern Ireland in many people's eyes while ignoring the jurisdiction's existence would mean no input whatsoever in shaping the policies adopted by the polity, regardless of its apparent temporary nature.

The inclusion of Article 12, with its Boundary Commission, in the Treaty gave hope to nationalists of the transfer of much of northern territory to the Free State, with many feeling they could continue to ignore and obstruct the northern jurisdiction, particularly in areas of nationalist majorities.

The Treaty resulted in differing opinions and strategies being adopted by nationalists within Northern Ireland. While Fermanagh County Council remained defiant and refused to recognise the Belfast parliament, Tyrone County Council acknowledged the de facto jurisdiction of that parliament in view of what was described as "the temporary period during which the northern parliament is to function in this area".

Derry City Corporation was divided between Sinn Féin members who urged unqualified allegiance to Dáil Éireann and nationalists who believed Derry City would benefit from a nationalist-leaning mayor and corporation officially making the case through the Boundary Commission for the city's inclusion in the Free State.

As chairman of the provisional government of the Free State from January 1922, Michael Collins believed it was essential to continue with the non-recognition of the northern parliament, "otherwise they would have nothing to bargain with Sir James Craig (the Northern Ireland prime minister)".

Collins oversaw the financing of the salaries of teachers and school managers who refused to recognise the northern educational ministry. For 10 months between January and October 1922, some 800 teachers in 270 schools (about one third of the schools under Catholic management in the north) refused to accept their salaries from the northern government and were paid by the provisional government instead.

It held examinations in the Intermediate Schools under Catholic management in various parts of Northern Ireland too. The provisional government was also extremely tardy in transferring civil service personnel and files to Belfast.

There were approximately 120 officials seeking to be transferred to the Northern Ireland government whose transfer was held up by the provisional government. Files from the Land Registry were still not transferred to Northern Ireland by March 1923, leading one civil servant to claim: "It really is monstrous that this obstruction should continue."

Nationalists calling for some form of recognition were not helped by the northern government's policies towards nationalists. Instead of reaching out to nationalists and Catholics, the northern government pursued policies guaranteed to alienate the minority population.

It seemed lost on unionist leaders that nationalism's "seditious" and "disloyal" policy of non-recognition was strikingly similar to the one pioneered by Ulster unionists in their opposition and obstruction of home rule less than 10 years previously...

In 1922, the northern government doubled down on its policies, policies taken solely in the interests of unionism while serving to alienate the nationalist majority, by abolishing Proportional Representation (PR), compelling public bodies and their employees to pledge an oath of allegiance to the crown, and gerrymandering regions to reduce radically the number of local councils held by nationalists.

As the non-recognition policy persevered, Collins was pressurised by provisional government colleagues such as Arthur Griffith, W.T. Cosgrave and Kevin O'Higgins to end it, claiming it was hampering border nationalist majorities for inclusion in the Free State through the Boundary Commission and the paying of teachers' salaries was impractical in the long-term.

Even before Collins was killed in August 1922, the cabinet resolved earlier that month to end its non-recognition campaign. Spearheaded by Ernest Blythe, a new policy prevailed to recognise the northern government and to discontinue the obstructionist policies.

Northern nationalist politician Cahir Healy, as an internee of the converted prison ship the Argenta, in the summer of 1922, summed up how many northern nationalists felt, "abandoned to Craig's mercy... Personally, we must look after ourselves".

As the years went by, this sense of abandonment only increased further within the northern nationalist community.

::Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).