ON DECEMBER 23 1920 the Government of Ireland Act 1920 received the royal assent from King George V. Despite the significant opposition to the Act at the time, it became operational with the establishment of Northern Ireland in May 1921, resulting in the partition of Ireland.

While the Act was introduced to safeguard the unionist minority of north-east Ulster, it had the effect of creating new minorities in Ireland without guaranteeing any safeguards for them, particularly so in the case of northern nationalists.

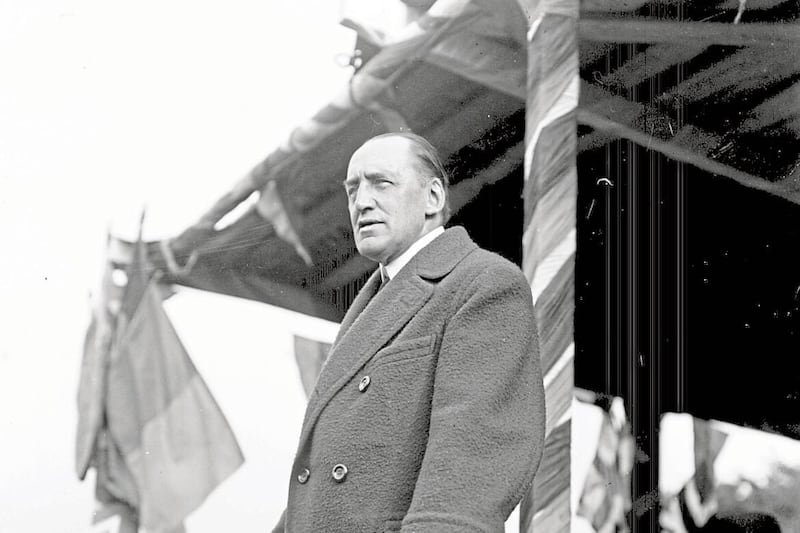

The genesis of the Act came in the latter half of 1919. Home Rule was still on the statute book since 1914 and could no longer be postponed. It was scheduled to come into operation automatically when hostilities were formally concluded with the signature of the last of the peace treaties after the First World War. To prevent this, the British prime minister David Lloyd George set up a committee chaired by cabinet member Walter Long to draft another bill, the Government of Ireland Bill.

The make-up of Long’s committee was unionist in outlook. There was no nationalist representation whatsoever nor was the advice of any nationalist sought. Leading Ulster unionist James Craig and his associates were the only Irishmen consulted during the drafting of the bill.

Long’s committee rejected the idea of holding a plebiscite in Ulster, with Arthur Balfour claiming plebiscites were only suited to "vanquished enemies".

The committee proposed to create two distinct legislatures for Ulster and the southern provinces, linked by a common council, comprising representatives from both. This was the first time a British government proposed a separate parliament for Ulster.

Before the end of the war, the exclusion of Ulster, or at least some of Ulster, was the only option being considered in terms of special treatment for the province. The common council proposed in the Government of Ireland Bill was a Council of Ireland to be composed of 20 members from each Parliament. The British government publicly claimed it hoped the council would lead to "the peaceful evolution of a single parliament for all Ireland".

The leading nationalist MP left in Westminster, Joseph Devlin, believed the creation of a parliament for Ulster would result in the "worst form of partition and, of course, permanent partition".

The Ulster unionist leader Edward Carson saw some attractions to an Ulster parliament, stating, "Once it is granted, it cannot be interfered with". He also stated the desertion of Protestants in the south "cuts me to the quick", but the reality was that there was "no alternative to the Union unless separation".

The Irish News described the Bill as "a plan devised by unscrupulous politicians to assassinate Ireland’s Nationality". The Freeman’s Journal deridingly named the Bill, "The Dismemberment of Ireland Bill".

With Sinn Féin in the ascendancy in the south and west of Ireland, the British government knew the Bill was unenforceable outside Ulster. The Bill was drafted and amended just to accommodate Ulster unionists. It was an attempt to solve the Ulster Question and not the overall Irish Question.

The amendments accepted included the limiting of the powers of the Council of Ireland from the Bill’s original draft, and the ability to remove the Proportional Representation (PR) system of voting after three years, measures Ulster unionists sought and were granted to make partition more durable.

Initially, there were many objections from Ulster unionists who did not seek their own parliament. The main problem was with the area to be included in the Ulster parliament. Ulster unionists sought the six counties of Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone, and not the nine counties of Ulster as this was the maximum area they felt they could dominate without being ‘outbred’ by Catholics.

James Craig, who became Northern Ireland’s first prime minister in 1921, even suggested the establishment of a Boundary Commission to examine the border area for northern and southern Ireland to avoid the jurisdiction of the northern parliament extending over the whole of Ulster. Subsequently, he emphatically opposed the "odious" Boundary Commission established under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. By that stage he had his northern "citadel" which he intended to sit on "like a rock".

The decision of the Ulster Unionist Council which was accepted by the British government was deeply unpopular among the 70,000 Protestants of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan who were sacrificed to the southern administration. Belfast unionist MP Thomas Moles explained that the three counties had to be abandoned in order to save the six counties: "In a sinking ship, with life-boats sufficient for only two-thirds of the ship’s company, were all to condemn themselves to death because all could not be saved?"

Even though the Ulster unionists endorsed the Government of Ireland Bill reluctantly, many eventually "concluded that the scheme proposed in the Government of Ireland Act would cause the least diminution of their Britishness". Some, such as Craig’s brother Charles, began to see the great benefits Ulster unionists would garner from having their own parliament: "The Bill practically gives us everything that we fought for, everything we armed ourselves for".

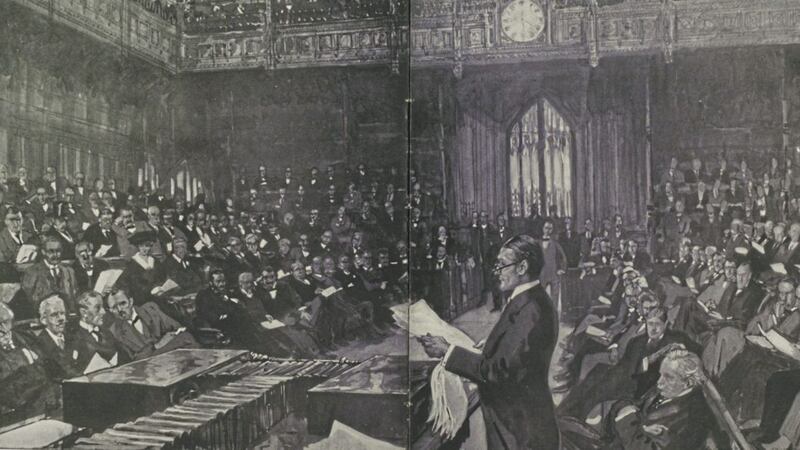

It has often been cited that the Government of Ireland Bill was allowed to pass relatively unchallenged due to the vacuum in nationalist representation at Westminster. There were just seven Irish nationalist MPs remaining (six from Ireland and TP O’Connor from Liverpool) after the 1918 general election, instead of 80, due to the 69 (who held 73 seats) Sinn Féin MPs/TDs abstaining and establishing Dáil Éireann.

It could be argued that even 80 nationalist MPs would have made little difference considering the make-up of the House of Commons after the election – the Conservative Party, Lloyd George’s Coalition Liberal Party and Irish unionists won over 500 seats, an overwhelming majority.

What little voice the seven nationalist MPs had was further diminished by the Catholic Church’s belief that they should not participate in the committee stages nor suggest amendments to the Bill. The Catholic Church was virulently opposed to partition and believed that participating in the framing of the "Partition Bill" would be seen as a sign of its acceptance.

The Bishop of Derry Charles McHugh claimed Catholic Ulster would never submit to "become hewers of wood and drawers of water for Sir Edward Carson". Joe Devlin condemned the bill as "conceived in Bedlam". He voted against it but did not in any way contribute to its final shape.

With Sinn Féin’s policy on partition almost non-existent, it chose to ignore the Government of Ireland Bill. As the Bill was making its way through parliament, the British government was waging a war with Sinn Féin and its military wing, the IRA.

Sinn Féin leaders stuck steadfastly and naively to the view that Ulster would readily come into an all-Ireland parliament once Britain was removed from the island. Sinn Féin failed to grasp the intense hostility Ulster unionists felt towards being governed from Dublin. That the Government of Ireland Act came into law as Britain was at open war with Sinn Féin, supported by a considerable majority on the island, shows the total air of unreality that surrounded the Act.

It was in an atmosphere of violence and boycotts that the Bill became an Act 100 years ago today, a "ghastly Christmas gift", according to The Irish News.

Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland.