WITH the electoral destruction of the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1918, Sinn Féin became the effective voice of Irish nationalism. At this juncture, the partition of Ireland loomed largely. And yet, Sinn Féin had no coherent policy on the issue. It was devoid of clear strategies to deal with it.

One of its first decisions directly relating to the north was to start a boycott, a counter-productive decision that in many ways increased the likelihood of partition.

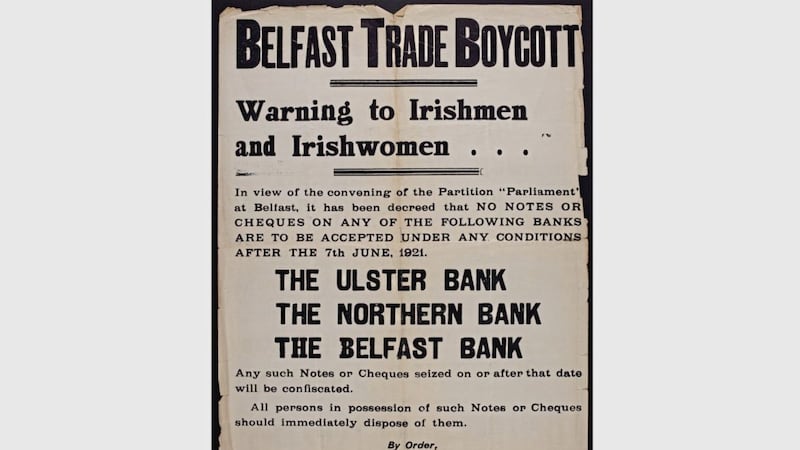

The expulsions of mainly Catholic workers from the Belfast shipyards and other places of work and sectarian violence in the north during the summer of 1920 were the catalysts that resulted in the Belfast Boycott. In August 1920 Dáil Éireann imposed a boycott of goods from Belfast and a withdrawal of funds from Belfast-based banks. In reality the boycott soon extended to other businesses and farming and beyond Belfast too.

Many saw it as an anti-partitionist move, a way to show that the north could not survive without the rest of Ireland. There was not unanimity for the boycott within the Dáil, with northern-born Protestant TD Ernest Blythe claiming "it would destroy for ever the possibility of any union", a view echoed by Countess Constance Markievicz. Despite the opposition, the Dáil and its cabinet approved the instigation of the boycott.

Erratically pursued in 1920, the Belfast Boycott was enforced in earnest from 1921. The appointment of Joseph MacDonagh as boycott director and the allocation of £2,500 gave the campaign impetus to apply economic pressure on the north east of Ireland.

An advisory committee was formed, inspectors appointed, and enforcement committees created around the country to ensure the boycott was obeyed. By March 1921 there were 184 committees dotted around the country; by May there were 360. It still was enforced intermittently.

The boycott involved members of the IRA intercepting and destroying products that originated in the north east and southern traders were banned from doing business with their northern counterparts.

In Monaghan, where the boycott was effectively policed more than anywhere else, shopkeepers were cautioned by the IRA not to deal with Belfast firms, and members of the public were warned not to enter the shops of those who were supplied from Belfast.

To prevent goods from entering regions, trains were raided by the IRA. Sometimes the raiders were unable to resist the temptation and commandeered items for themselves. A Monaghan brigade who seized whiskey, "could not burn the whiskey – it would be sacrilege – we took it away and buried it".

Instead of burning captured Gallagher’s cigarettes, an IRA unit extracted the cigarettes from the packets and put them into “Slainte” packets, and sent them to those interned in Ballykinlar camp in Co Down.

Blacklists were published with the names of local and national firms to be boycotted. Members of Cumann na mBan issued blacklists of firms handling Belfast goods. Women played a significant role overall in enforcing the boycott, through running boycott committees, raiding shops and trains, and holding protests.

‘White Lists’ were also issued of firms not to be boycotted, those considered not responsible for expelling Catholics from their workforces. Despite this, nationalist firms in Belfast were negatively affected by the boycott too. Denis McCullough, one of the organisers of the IRB in Belfast, was forced to close his bagpipe factory because of the boycott, as "the Irish public… buy British-made pipes rather than support this purely republican firm".

The most common form of punishment inflicted on firms trading with Belfast companies or banks was financial – fines were imposed. Normally goods were burned or destroyed, not homes nor business premises, although some were targeted in the almost 800 arson attacks in the first six months of 1921 alone across Ireland.

Sinn Féin claimed the boycott was achieving results. Many wholesale firms declared they were badly hit, losing 75 per cent of their trade outside of Ulster. Northern salespeople on the road frequently returned with no orders. MacDonagh boasted that "except in Antrim and Down it was impossible for a Belfast merchant to sell as much as a bootlace in any other part of Ireland".

With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and the subsequent establishment of the provisional government, the rescinding of the boycott formed part of the first Craig-Collins Pact of January 1922. In return, James Craig promised to facilitate the return of expelled Catholic shipyard workers to their jobs. The Belfast Boycott was discontinued but Craig failed to secure the return of many Catholics with just 20 Catholics out of thousands reinstated in the shipyards by the end of January.

Shortly after the boycott was rescinded, the anti-Treaty IRA imposed it again, much to the embarrassment of the provisional government. Within months, there were many incidents of "unauthorised persons" enforcing the boycott, causing the government to issue a warning that "the demands referred to are made without lawful authority".

Despite the warning, the boycott continued in many parts of the country. Ulster traders responded by forming a group, the Ulster Traders’ Defence Association, to impose a counter-boycott, claiming the boycott "is at present being carried on more bitterly than ever". Ulster people were urged not to buy any southern goods; clothing, meat, butter, biscuits, furniture, stout and whiskey.

The seizing of property in Dublin by the anti-Treatyites in the name of the ‘Belfast Boycott’, leading to the kidnapping of national army general JJ 'Ginger' O’Connell, who was held as hostage in the Four Courts, was the direct catalyst that started the civil war in Dublin. The government ordered military action on the Four Courts, commencing on June 28 1922.

With the start of the civil war in the south, the enforcement of the boycott became even more uneven and sporadic, eventually petering out. Its legacy of driving a psychological wedge between north and south continued far longer.

Economically, the boycott did have a negative impact on trade in Belfast and other areas in the north of Ireland. In all probability, Belfast trade with the south never recovered to its pre-boycott level, halved by 1924. The boycott also had a negative economic effect on those imposing it, resulting in goods costing more to the consumer and diminished profits for traders.

Northern-based banks such as Ulster Bank, Northern Bank and Belfast Bank saw business reduced, with deposits down and some sub-branches having to close in the south. The Belfast Bank lost one fifth of its deposits outside of Northern Ireland and decided to close all of its southern branches in 1923.

The boycott had minimal impact on the north's three main industries, though – agriculture, shipbuilding and linen – as they mainly supplied to international markets. Ernest Blythe claimed the "boycott would threaten the northern ship-building industry no more than a summer shower would threaten Cave Hill".

While its economic efforts to hamper trade in Belfast met with mixed results, the boycott’s aim to unify Ireland was an unmitigated disaster. It resulted in further psychological and physical divisions between north and south, some that had never existed before.

Writing in 1924, PS O’Hegarty had no doubts about its damaging effects, claiming the boycott "raised up in the South what never had been there, a hatred of the North, and a feeling that the North was as much an enemy of Ireland as was England… it was an utter failure inasmuch as it did not secure reinstatement of a single expelled Nationalist, nor the conversion of a single Unionist".

:: Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press).