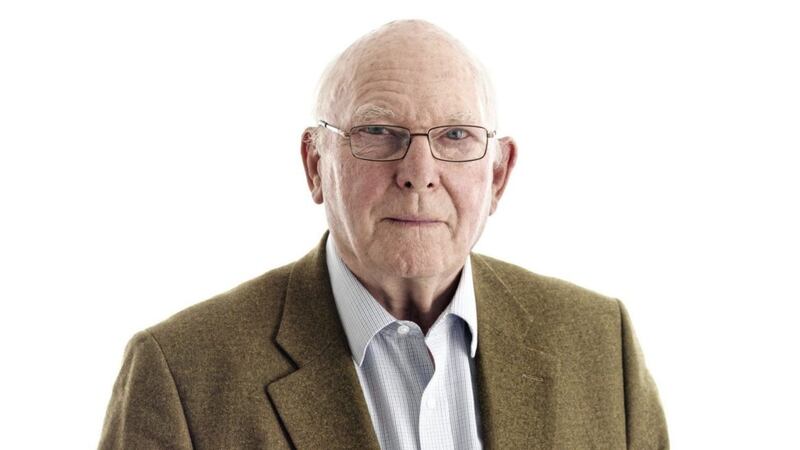

BESTSELLING novelist and ex-ITN reporter Gerald Seymour, whose thrillers about spies, undercover agents and terrorist threats have attracted legions of fans, chuckles as he recounts some of the close shaves he's had during his career.

"There were a few times when I felt scared," he admits, laughing. "But it wasn't about being among 'whizzbangs' so much as being on lonely roads, perhaps just myself and a driver, say in Lebanon at night amid burning oil drums and roadblocks, and windows wound down and youngsters jabbering away with Kalashnikovs, and not understanding a word. That was the most unnerving thing."

As a reporter, he covered events in trouble spots including Vietnam, Israel and Northern Ireland, as well as the Great Train Robbery and the Munich Olympics massacre in 1972.

Much of the tension he has experienced in front-line reporting has been transferred into his novels; his fiction career began in 1975 with his Troubles-set debut Harry's Game. The theme song of the TV series based on the bestseller, which was filmed in Belfast, was a top 10 hit for Donegal trad group Clannad.

Seymour has retained the suspense and tension of Harry's Game in his 35th novel, Battle Sight Zero, which follows the path of a Kalashnikov assault rifle from its manufacture in 1957 through six decades as it changes hands, to make its way in 2018 to wreak havoc on the streets of Britain.

At the heart of the story is the relationship between a Muslim girl from Dewsbury answering the terrorist call and an undercover agent tasked with infiltration.

While the closest Seymour has ever got to an AK47 is holding one in the Middle East, he says the weapon has a worldwide reputation and people know how much devastation it can cause.

"I spent most of my adult life being aware of the Kalashnikov, having seen it through all my time in the Middle East, in Vietnam and in Northern Ireland. More recently, we've seen the carnage with the Kalashnikovs at the concert in Paris."

At 77, Seymour shows no sign of slowing down. He has produced around a book a year since he gave up his reporting career to become a novelist in the 1970s.

"There had been the launch of The Day Of The Jackal. I knew of Frederick Forsyth. In Fleet Street and the broadcasting studios, there were reporters thinking they'd have a go. There was a genuine feeling that Forsyth had moved the whole world of thriller-writing on from Alistair MacLean and Hammond Innes.

"I came back from the Middle East war, the kids were at school, the office said I was to take three weeks off, so I thought I'd have a go," he recalls.

Harry's Game was an instant bestseller.

"It was a very easy ride," Seymour reflects, still surprised. "It frightened the hell out of me, because of what I was going to do for the next one."

Today, he says a lot of his success is down to his wife, Gillian, who bought him a £5 pine table from a junk shop on which to pen his stories, and looked after their two children while he was in war zones or researching his subjects.

They have two sons and three grandchildren, on whom he dotes.

"It's part of that thing that keeps you switched on and humble and able to see other generations' point of view. I value that hugely."

Does he miss the fast-paced world of TV news reporting?

"I miss the craic and laughter and gallows humour of the rat pack, but thank God, I'm too old for that now."

He reckons that front-line reporting has become more dangerous than it used to be.

"In my day, we thought that somehow we could talk our way through, and I don't think that exists any more. In fact, if you were in Syria in recent years, it's quite a coup [for insurgents] if they got their hands on you. It's much more dangerous and much more frightening.

"Social media is huge because you can't deny the opposition forces the oxygen of publicity. It's very hard to stamp on."

He also feels that society has become less shocked by atrocities which don't happen on their doorstep.

"We don't have the shock horror factor that we would have done 30 years ago. That means that the reporters' and cameramen's lives are in some sense cheapened. News is so much more transitory. People are probably less caring about situations abroad than they used to be.

"I hope that to a small extent, I can hint at situations through fiction more than a guy who's writing purely factual stuff in a daily broadsheet, or reporting from an armoured car on television. If one achieves a bit of that, then one would be quite pleased."

He says he needs a fairly quiet life to be able to concentrate the mind on crafting his stories, and admits that the process becomes more difficult with each book.

"The cliff gets steeper and the rock I'm trying to carry up gets heavier. I'm concerned more that this is going to be the end of the road and ideas and motivation will dry up. Thank heavens that hasn't happened yet."

:: Battle Sight Zero by Gerald Seymour is published by Hodder & Stoughton, priced £18.99.