THEY sit side-by-side in assured harmony, a diverse collection of unlikely companions who, at one time or another, might not have welcomed each other's company quite so warmly.

But here, in the downstairs exhibition centre at Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich on the Falls Road, Sinn Fein's Gerry Adams smiles benevolently across at Linda Ervine, sister-in-law of a former loyalist leader, while Bernadette Devlin (McAliskey) and Baroness May Blood look on in respectful silence.

There are many others in this cosy little get-together – John Hume, Fr Gary Donegan and singer Frances Black among them, all bright and bold and purposeful – in a revolutionary, Che Guevara kind of way.

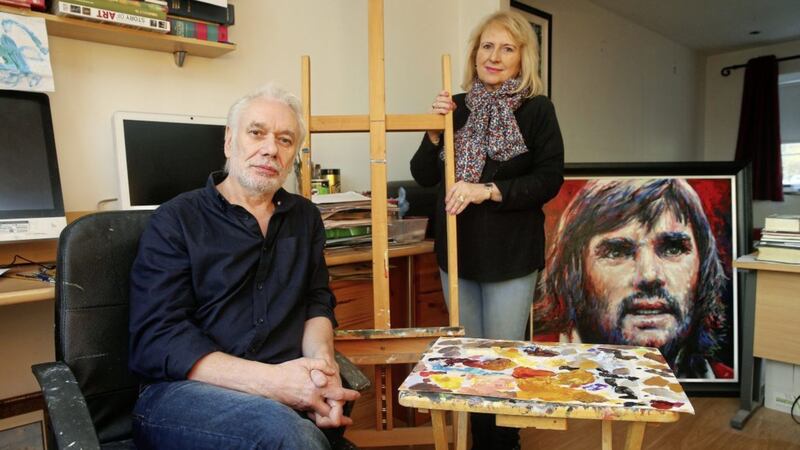

Belfast artist Tony Bell has included 32 portraits of his favourite Northern Ireland risk-takers (dead or alive) across language, culture and politics which, when painted in iconic 'Che' pop art style, have probably never looked so cool (apart, maybe, from George Best or Carl Frampton).

The exhibition, Special People, Special Places, was launched by former Holy Cross rector Fr Donegan – who didn't know he would also be unveiling his own portrait at the event – with the pictures mingling with some of the artist's striking oil landscapes of seas, valleys and mountains and also watercolours of his two grandchildren, Ollie (4) and Tony (2).

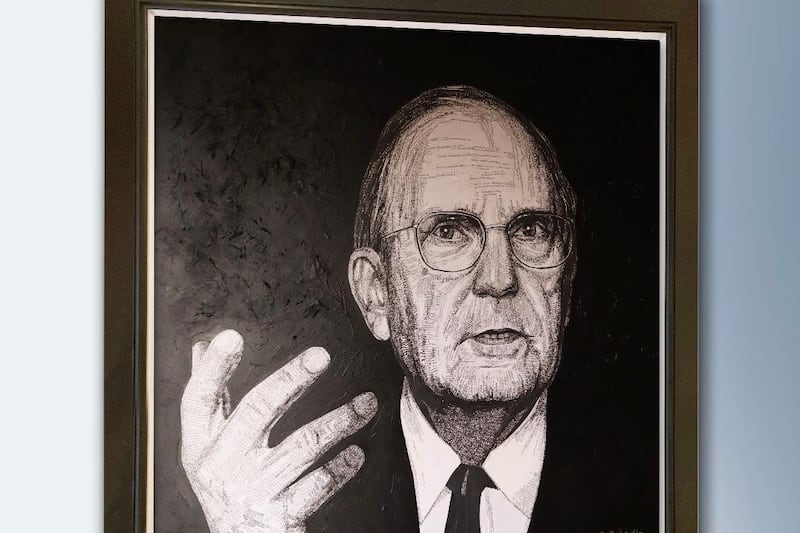

Another, distinctively different portrait of Seamus Heaney draws the eye, creatively composed with strategically placed pieces of torn up newspaper print.

"I chose the people because I like them all for different reasons," says the artist, a 63-year-old father-of-four whose name and public ranking ratcheted up dramatically following the unveiling of his much-lauded Martin McGuinness portrait at Stormont earlier this year.

"To me, they are people who have all gone out on a limb to promote ideas, while listening to what others have had to say. It was the 50th anniversary of the death of Che Guevara in 2017 so that is when I first had the idea of doing something in a similar style, only of local people who became known for change of some sort."

An ex-prisoner who became involved with the republican movement as a 17-year-old, ending up in the former Long Kesh prison where he served four years, Tony Bell is well placed to look back and appreciate the significance of new beginnings, both in a political and personal sense.

Now, "older, wiser and more mellow", he is no longer the anti-establishment, revolutionary figure of his youth and although still "a republican in outlook", believes reasoned argument is the only way forward.

"That's the way I am politically now," he says. "I hate sectarianism and I don't think you can force anybody to do anything. My father, who I never really knew that well, was from the Protestant tradition and would have played football for Northern Ireland, but he also played cricket for Ireland, so I think you have to unite people and respect both traditions. This place is too small not to."

An "idealistic" teenager, he was brought up by his mother and grandmother and met many other like-minded contemporaries, who, because of the Troubles, "got dragged into things that totally changed our lives".

"As a young boy, I read the Proclamation [of the Irish Republic] and then, when you hear how 13 people on Bloody Sunday were killed by security forces who are supposed to be there to protect people, well, it changes a young person's perspective on life," he argues. "But I wasn't a John Hume; I was just a young person who felt he had to react and do something."

He was sentenced to eight years in 1972 for being in the IRA and was out in four, using his time "inside" learning to draw, first on glass windows illegally removed from the prison toilet block and also on legally provided wooden plaques and handkerchiefs.

"We were rebellious and thought we could do anything," Bell reflects. "When we removed the windows out of the toilets, you could paint on the back of the glass, but you had to work backwards, putting on the highlights at the end.

"Che Quevara was a real iconic figure for us at that time and I became proficient in drawing him, mainly because I was asked so often by other inmates. There was a stencil which was passed around but I found I could draw him quite easily freehand."

His girlfriend at the time – they had only being going out together for a year after meeting at a youth club before his arrest – Pauline (now his wife), saw the beginnings of a talent and, unbeknown to the artist himself, enrolled him for art classes on his release.

"Pauline waited and stood by me," he says. "She worked in the design department of the BBC with people who had gone to art college and she really encouraged me and thought I was good enough to do the same. "By the time I got out, she had applied for me to go to art college."

He actually attended Ulster University's Belfast College of Art three times – first as an apprentice printer in 1971 before he went to prison – "that only lasted six months" – then for his degree in Graphic Design and Illustration, and, finally, for a degree in Irish, which he completed in 2008.

Looking back on his time in jail, he believes it didn't hold him back, but did help him to "grow up".

"I think it made me the person that I am now," he says, "but, certainly, once I had children, I totally dedicated myself to family life as I wanted a better life for them, so that was what I focussed on.

"I had felt for a long time that what was happening needed to end and the voice of reason was being drowned out, but I wasn't interested in entering into the political arena myself."

What he did do was enter the world of advertising and went to become one the first creative directors with AV Browne, working with many famous names in Northern Ireland – with no-one ever really knowing his background – and heading up some of the company's most memorable campaigns, including the Henry Hippo project for Ulster Bank.

After 16 years with the company, he embraced the challenge of running his own business before feeling the pull back to his first love – painting.

"Since the Martin McGuinness painting, I've been offered other portrait commissions, so I'm devoting some time to that in January," he says. "It strange the way life comes full circle: I recently went to see an art exhibition in the Ulster Museum by a former loyalist prisoner, Geordie Morrow, who had been secretly painting republican prisoners when he was in the 'cage' next to us in Long Kesh.

"The museum facilitated the visit and I talked to him about painting – it was a good exhibition and I think he captured the feel of the prison very well at that time. It brought home to me the surreal path of life – and that, when you talk to people and listen, you realise we're not that very different at all."

:: Special People, Special Places continues at the Dillon Gallery in the Culturlann until January 25.