HANNA Sheehy Skeffington is Ireland’s best-known campaigner for votes for women. Cork-born but living all her adult life in Dublin, she also had strong connections with the north. She was a regular visitor during the suffrage years, heckling Winston Churchill when he came to Belfast and speaking with her husband Frank at a lively meeting in Ormeau Park.

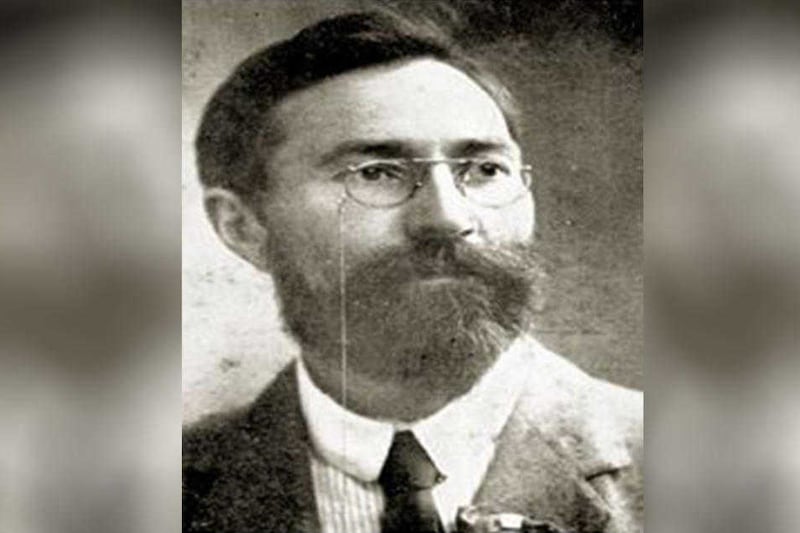

Frank Skeffington, born in Cavan and reared in Downpatrick, was proud to be an Ulsterman. His brutal murder in 1916 shocked people around the world. His widow’s determined campaign for truth and justice is one that inspires respect. There are many parallels with the experiences of those here who, in the past decades, have also lost loved ones through the actions of state forces.

The Sheehy Skeffingtons were close friends with leaders of the Easter Rising, James Connolly and Thomas MacDonagh in particular. While Hanna travelled to the GPO to bring supplies and to offer support, Frank accompanied her for a very different reason. As a pacifist, he disagreed with armed insurrection but he supported the ideals of the Rising and wanted to see Connolly to discuss how looting and disorder in Dublin city centre could be prevented.

Frank decided to form a citizen’s militia and tried to encourage people to join him. No-one turned up for his meeting so he set off for home, reaching Portobello Bridge in the early evening. He was then arrested, "unarmed and unresisting" and brought into Portobello Barracks in Rathmines.

Shortly afterwards, hands tied behind his back, he was taken out and used as a hostage in a raiding party organised by Captain John Bowen-Colthurst. Houses were fired at and a young boy shot dead. Two other journalists, Thomas Dickson and Patrick McIntyre, both unionists in their political views, were also arrested and the three brought back to Portobello barracks.

The following morning they were marched into the yard of the barracks and a firing party of seven shot them dead. That night, his body tied in a sack, Frank was buried in secret in the barrack yard. His family was not informed. During frantic searches in the chaotic streets of Dublin Hanna’s sisters, trying to find out what had happened, found themselves arrested.

Bowen-Colthurst ordered a raiding party to the Sheehy Skeffington house. The British were attempting to find evidence to justify the murder. It was only on the Friday that Hanna finally discovered what had happened to her husband.

Her contacts with the suffrage movement in Britain and America were now to prove invaluable. With the support of Sir Francis Vane, an officer who had been stationed in Portobello, and who was horrified at events, she managed to get Bowen-Colthurst court-martialled.

The verdict, guilty but insane, led to a chorus of protest. Colthurst was sent to Broadmoor, where he spent less than 18 months before sailing off to a new life in Canada, continuing to receive a retired officer’s pay.

Hanna had not achieved either truth or justice so, despite her grief, she continued to campaign. She met Prime Minister Asquith in Downing Street. He tried to bargain with her. Would she be satisfied with an "inadequate inquiry", which was the best he could offer? She refused that and the offer of £10,000 compensation, rejecting it as "hush money".

But Asquith did grant an inquiry. Chaired by Sir John Simon, it began on August 23 in the Four Courts in Dublin and lasted six days. Although the inquiry was inadequate – Bowen-Colthurst himself was not called upon to give evidence – the main facts were dragged out of reluctant witnesses and the indiscriminate murder of civilians made plain.

While Hanna had the consolation of knowing that she had achieved with her persistence "a damning exposé of militarism", she was not satisfied. She decided that she would go to America in order to tell her story in a country that still had a free press. Britain, in the middle of war, suppressed information through the use of the Defence of the Realm Act.

However, she was refused a passport and had to smuggle over herself and her young son Owen using assumed identities. While in America she was tailed by secret service agents who reported on her meetings. In the next 18 months she spoke at over 250 meetings, and succeeded in gaining an interview with President Wilson, the only Irish activist to do so.

She published an account of Frank’s murder and its cover-up in a pamphlet British Imperialism as I have Known it which was reprinted many times. Shortly before her death in 1946 she added a new preface. Her words have a great resonance with the experiences of families like the Finucanes and those in Ballymurphy who have campaigned for justice over many years:

"As I look back, across the space of 30 years, on the events narrated here, one impression emerges more clearly than ever, namely, that it is not the brutality of the British army in action against a people in revolt (we learned to take this for granted and indeed it is part of war everywhere) but the automatic and tireless efforts on the part of the entire official machinery, both military and political, to prevent the truth from being made public.

"This was wholly characteristic of the British regime in Ireland: it is this more than any individual crime or atrocity which damns beyond redemption the whole apparatus of British Imperialism."

By the time she was ready to return home to Ireland in July 1918 she described herself as a Sinn Feiner, ready to take her part in the new national movement. But, docking at Liverpool, permission for her to continue to to Ireland was refused. She petitioned politicians, eventually smuggling herself home, hiding in a ship’s hold.

Not long after she arrived home, she was arrested as an illegal immigrant, and sent back to England, to Holloway jail. She went on hunger strike and was released, returning to Ireland, now an executive member of Sinn Fein.

When the northern state was established Hanna was served with a banning order, which she often quietly ignored, in order to continue to visit Skeffington relatives. However in 1933, crossing the border to speak on behalf of women imprisoned in Armagh jail, she was given a one-month prison sentence. In court, asked if she wished to say anything to the charge, she replied that it was fully proved:

"I make no denial or apology for having been in Co Armagh or any part of the 32 counties. I recognise no partition. I recognise it as no crime to be in my own country. I would be ashamed of my own name and my murdered husband’s name if I did. I believe the time will come when partition will be as dead as Queen Anne. I am satisfied that I, personally, can be a pointer, through this action of the authorities, in helping to bring about the death-knell of partition."

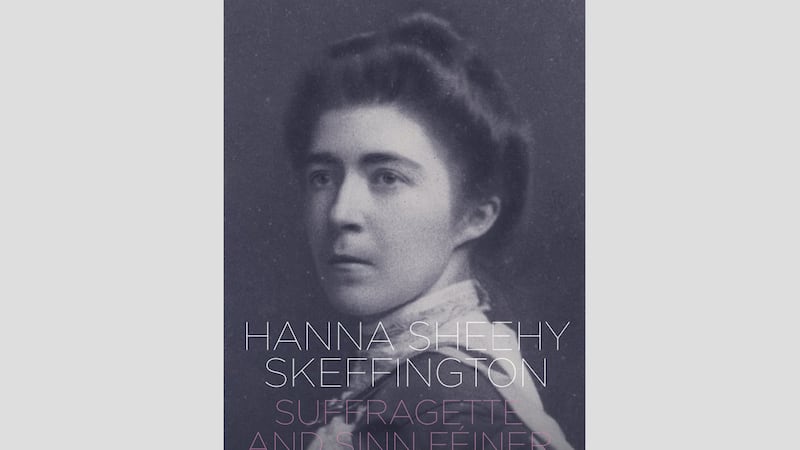

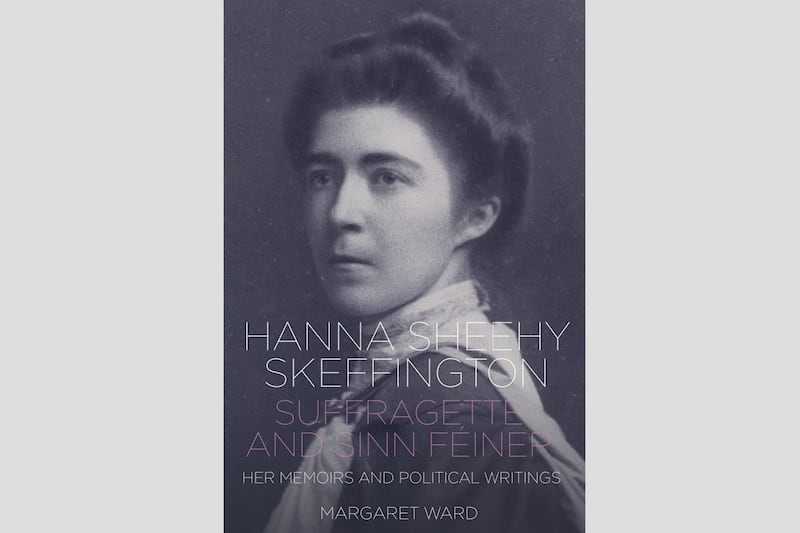

:: Dr Margaret Ward is the author of the newly published Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Suffragette And Sinn Feiner (UDC Press, £30), which will be launched by Professor Monica McWilliams at the No Alibis book store, Belfast, at 5.30pm on Thursday October 12.