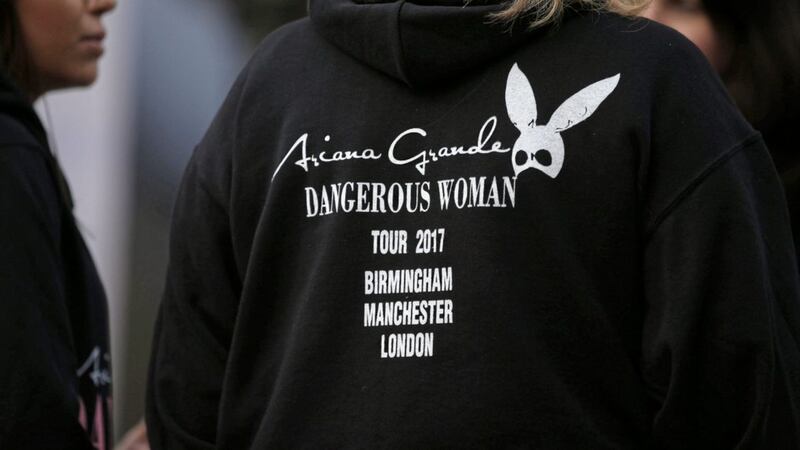

I FLEW to Malaga in the Costa del Sol for a sun, sea and sangria holiday last Tuesday morning with the news of the bombing of the Ariana Grande concert in Manchester still filtering through.

The idea that someone would set out to murder teenage girls at a pop concert sent shivers of revulsion to my core. Young people are dying violently all over the world but the geographical proximity to Manchester and remembering the horrors that happened in my own home town made the attack hit home even more strongly.

To be honest, though, I didn’t give it much more thought, walking in 25C heat along sandy beaches during the day and enduring karaoke sessions in the evenings. (It was weird seeing the over 60s singing their hearts out to punk songs until you realized that punk flourished in 1976/7, 40 years ago and time has smoothed their edges – the people and the songs.)

But then I read an article in the Journal of Music, an Irish online magazine, by Toner Quinn, son of film-maker Bob Quinn and a fine traditional musician and writer. Toner was writing about the Manchester killings and the role of music in our society.

Also, recalling the attack on the Eagles of Death Metal concert at the Bataclan in Paris in 2015, he noticed how so many commentators mentioned music as a means of bringing people together, creating bonds and community.

Regular readers of this column will know that many of the musicians I interview talk about tradition and about community. Cathy Jordan of Dervish, put it best when she told me: “What we love is the colloquial, and the Leitrim Equation as it’s known gave us the opportunity to do something we hadn’t done in years, that is to completely ensconce ourselves in a community and you go to their schools, to their old folks homes and to their pubs and you get surrounded by the wealth of people and all they have to offer. It was a phenomenally moving experience,” she said.

However, according to Toner: “We have access to more music than ever today, but the obsession in the tech world is to fill us up with what we know, rather than expand our listening and understanding of music and other cultures in any deep way.”

I know what Toner is saying but disagree to a point. It might be the case with more popular or commercialised forms of music but so-called traditional musicians are often at the forefront of what is called “fusion”, a term not everyone likes.

This was recognised by the south Armagh-born Mancunian singer and flute player, Ríoghnach Connolly who spoke of her early experience of settling in and making music in Manchester.

"It was beautiful because we have that shared history and musically, there is a huge Indian classical scene here I have loads of Muslim friends and I am seeing them suffering a lot now. So musically, there was a lot to bond me with Manchester," she explained.

So can music be used to bring otherwise disconnected people together? Of course it can.

Despite the “two communities” theory, the “never the twain shall musically meet" trope, you will find all kinds of backgrounds among an audience at a traditional music gig. It’d be the same for grunge or death metal or country and western, but traditional music in this place is thought by the gullible to have a subliminal political message. It doesn’t.

There certainly is a message in music and it is that, under the skin, we are all the same. As Ariana Grande said in her statement after the atrocity: “Music is meant to heal us, to bring us together, to make us happy.” The striving for happiness is universal.

At the same time, music and song can be made to suit sectional interests. Francie Brolly’s The H-Block Song is one of the finest expressions of a political idea I have ever heard but I know not everyone will admire its sentiment.

Orange songs can unite a group of people in order to differentiate them from others, used to confirm and strengthen a self-identity and as a shield against an enemy, real or perceived. I recently came across the Orange Minstrel or Ulster Melodist: Consisting of Songs and Poems by Robert Young, described as the Fermanagh True Blue.

The aim of the book was to “circulate, in a brief but impressive manner, warnings to the present and the future generations of our people, which may be of incalculable use to them, in raising and cherishing a spirit of unity in those, whose dearest rights are in progress of being for ever wrested from them, by the secret workings of jesuitical conspirators against the religion of their Bible, and the dominion of their king.”

The songbook was published in Derry in 1832.

Toner Quinn contends that is only by opening our ears to the musics of other cultures so we can see what touches the hearts of people different to us can we bring the different strands of humanity closer together, a buffer against politics and religion. The two examples above might be a good start.

However, he believes that the homogeneity that mass dissemination of music on your phone, your laptop, your tablet creates a huge stumbling block.

“How can we sensitively and carefully find the moments of cultural understanding in all our musics if we allow Facebook, YouTube and Spotify decide all our future listening for us?" he asks.

There were two series of a great programme called Ceolchuairt on TG4 some years back. It produced some of the best TV I have ever watched. In it, trad musicians went to different parts of the world to see what connected Irish music to music from other parts of the world, so Kila went to India to hear classical music, Moorland Nic Amhlaoibh went to sing with Bulgarian choirs, Armagh's Daire Bracken went to Mongolia to learn their famous throat music.

The results were uplifting, funny and profound and portrayed our common humanity through music. That surely is something the world needs a lot more of after Manchester and the Bataclan.