ROBERT Millar and Samuel Donaldson were the first RUC officers killed by republicans in the Troubles, blown up when they went to examine a booby trapped car near the border on the Crossmaglen-Dundalk Road on August 11 1970.

After the explosion, former Nationalist MP for the area Eddie Richardson stated that he knew “for a fact that everyone in Crossmaglen is very depressed and annoyed about this whole incident”.

Reporter and broadcaster Henry Kelly visited the village and found that unlike Derry, Belfast or even nearby Armagh, Crossmaglen was peaceful and “never a flashpoint”. An editorial in a local paper stated the RUC men’s deaths “were all the more unfortunate as the occurrence took place in an area where political and sectarian strife have been singularly absent”. At the inquest, the police asked for their appreciation for the support they received from people in Crossmaglen to be put on the record.

Perhaps this account of these early RUC casualties will surprise some readers. Crossmaglen is more popularly cited as an epicentre of ‘bandit country’. Much of what has been written about the Troubles has focused on the urban centres of Belfast and Derry. The border area has been left significantly under researched and much of what has been written has tended towards the bandit country cliché. Perhaps in the context of talk of a ‘hard border’, now is an opportune time to revisit the recent history of the border counties.

The simplistic narrative that currently exists is that the border areas, on both sides, were a hotbed of latent republicanism. IRA activists used the boundary as an escape route to the south where they were met with a mixture of connivance and ambivalence by local populations and the southern authorities. However, the situation was more nuanced.

The Irish state felt disproportionately threatened by the IRA and the entire thrust of its security policy was focused on containing the republican movement domestically. This had massive long-term implications for such areas as cross-border security cooperation, loyalist attacks south of the border and Garda-republican relations.

The first visible sign of the Troubles in border communities was the arrival of ‘refugees’ from Northern Ireland. These were largely groups of women and children fleeing the violence and they initially received a warm welcome.

They mostly arrived during the marching season in 1969-1972 – 5,000 refugees were accommodated by the Irish state on one day in the summer of 1971.

However, attitudes to the arrivals from parts of the southern media, as well as some government officials, soon soured. Contributing to a recent study, one northerner compared her experience with that of modern day migrants. She recalled her experience of suffering “the same inane prejudices targeted at the foreign nationals who are accused of getting benefits and jobs belonging to locals”.

As illustration, a particularly unsympathetic RTE report concluded that the ‘refugee’ holding centre in Gormanstown could “provide a refuge from marital problems or even just a comfortable retreat for the mildly neurotic or over nervous”.

Given events occurring in Belfast in particular, this was an especially crass observation.

Of course, there were less visible signs of the northern conflict than the refugees' arrival. Removed from public view, republicans and nationalists came south to receive military training. Often this was provided by veteran republicans; on at least one occasion, at Fort Dunree in Donegal, a group of nationalists from Derry received military training from the Irish army. However, throughout 1969 and 1970, the border remained largely removed from the conflict.

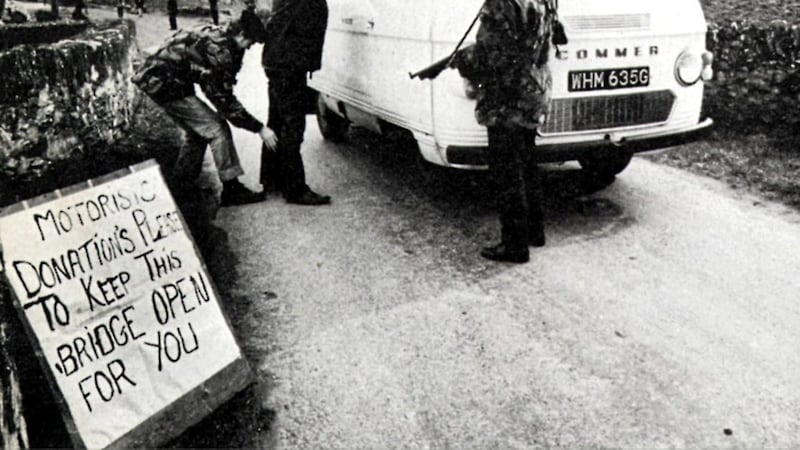

Summer 1971 was to be a watershed. With internment in August, many nationalists, including republicans, fled south. There was a notable upsurge in violence on the border. This led to pressure from the unionist community for the border roads to be closed. The British army moved in to ‘crater’ or ‘spike’ roads which locals would later attempt to reopen.

Some roads were closed and then reopened dozens of times. Irish minister for justice Desmond O’Malley, a staunch critic of the IRA, cited the ‘cratering’ of border roads as a significant element in radicalising border communities, arguing “the simple unchallengeable fact about trouble in border areas is that there was no trouble of any kind worth mentioning until the unionist administration, for their own political purposes, persuaded a credulous British government to send out the British army to implement a policy of ‘cratering’ roads in border areas”.

Statistics gleaned from archival research support O’Malley’s argument. Before internment, there were on average four border incidents a month; after internment there were 16; after ‘cratering’ there were 33.

The British ambassador in Dublin Sir John Peck had warned his superiors of the long-term implications of closing border roads. There is no suggestion of a return to ‘cratering’ in the event of a ‘hard border’. Nonetheless, those with a blasé attitude about the implications of interfering with cross border travel and trade could do worse than heed Peck’s warning.

:: Patrick Mulroe is the author of Bombs, Bullets And The Border: Policing Ireland’s Frontier: Irish Security Policy, 1969-1978, published by Irish Academic Press.