OVER the course of the last month, the sporting scene in Japan has ground to a halt amid growing fears over the coronavirus spread. The Nippon Professional Baseball League season had been due to open on March 20 but has been postponed indefinitely.

No matches have been played in soccer’s J League since February 23. Golf’s Japan Championship, a PGA Tour Champions event which was due to take place in Chiba in June, is cancelled.

The country’s top Rugby Union league, home to World Cup winners Dan Carter, Kieran Read and Brodie Retallick, completed six rounds of games before being suspended. Those organising the Tokyo Olympics held out for as long as they could before eventually succumbing to the inevitable earlier this week; the Games will take place in 2021 instead.

And then there’s sumo.

The fact that the sport’s March basho – a bi-monthly professional tournament - went ahead as planned, albeit behind closed doors, tells you plenty about the ancient attitudes that prevail.

It is a world in which Roscommon man John Gunning has been immersed for 16 years, first as a competitor, then coach, and now as commentator and newspaper columnist.

“Calling off the event completely would undoubtedly have been a safer course of action,” he wrote in the Japan Times earlier this month.

“Closed doors or not, there are still risks involved of course. Measures are being taken to limit interpersonal contact, but controlling the movement of 700 people day and night for two weeks is a near-impossible task, and if a rikishi becomes infected with Covid-19, serious questions will be asked.

“The nightmare scenario, of course, would be a member of the general public in the region contracting the virus from someone in the association. The repercussions for the sport’s governing body in that case would likely be severe and long lasting.”

After 15 days of competition, the basho came to a close last Sunday.

As that column clip shows, he has no fear of shining a light on uncomfortable issues inside sumo. Gunning has been outspoken, for example, on the continued freezing out of female participants - a tradition stemming from Shinto and Buddhist beliefs that they are "impure" because of menstrual blood.

Then there’s the “ticking timebomb” of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy) and concussion in an at times brutal, violent arena. More on that later.

“I’m on the English speaking side of the media so my influence on the sport is probably pretty limited - some people think I’m the wasp at the picnic and others think I’m the ultimate yes man. You can never win, but that’s the nature of the job.

“You’re not as free as you would be in some other countries to say what you want, but I try to push the envelope and ask important questions.”

The 19 years spent in Japan so far are all interwoven into Gunning’s own sumo story; from the first day he walked into Komatsuryu Dojo - one the most prestigious clubs in the country - to representing Ireland at three World Amateur Championships before hanging up his mawashi in 2012.

Having sustained broken bones, shattered teeth and a fractured skull in pursuit of progress, Gunning has earned the right to ask questions.

But here’s one for him: how does a man from Castlerea, the second largest town in the county with a population of roughly 2,000, find himself so close to the bosom of an indigenous way of life, one whose history and tradition spans centuries?

Now there’s a story.

**********************

WALTER Payton, Jim McMahon, William ‘The Refrigerator’ Perry – these were the guys who captured the imagination. The local GAA club, St Kevin’s, had a decent history of its own, four county titles and one Connacht by that stage. Castlerea Celtic are one of the oldest soccer clubs in the country. Manchester United were his team across the pond, despite enduring a decade to forget.

But there was something exotic about American football. Especially then, especially to a young lad finding his way in mid-80s Ireland. The razzmatazz, the pageantry, the fanfare and the flash… those fleeting glimpses snatched at on RTE every now and again left John Gunning intoxicated, craving more.

It was so wildly different to anything else he had seen before; there was a huge appeal in that then, just as there is now.

Music was a lifeline to the world beyond county borders too. The hair rock phase at the latter end of the decade eventually morphed into something a bit dirtier, a bit more raw, thus the early ’90s Grunge scene was born.

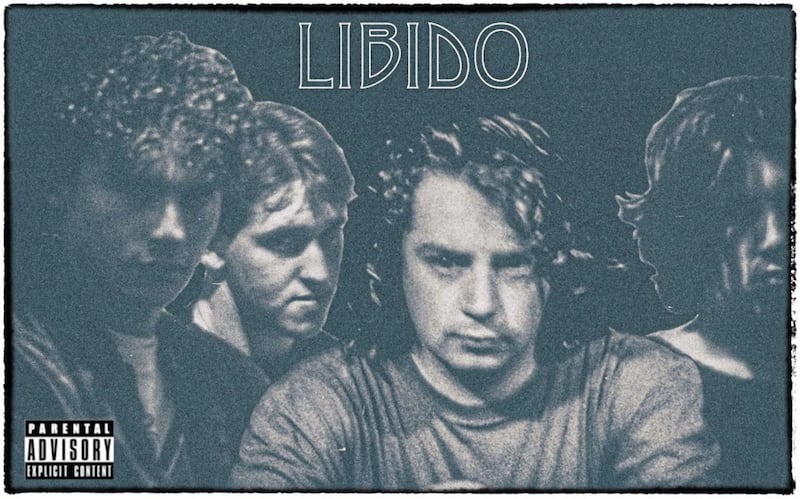

A few weeks back Gunning posted a picture on Twitter of a mocked-up album cover, himself front and centre, long curly locks flowing freely, the main man glaring moodily into the camera like a midlands Michael Hutchence.

Flanked either side by university pals from Mary Immaculate College in Limerick, the magnificently named Libido meant business. And, by God, they had it all.

Almost.

“We had literally everything going for us – we had attitude, the look, the desire,” says the 46-year-old, speaking from his Tokyo home.

“The only problem was not one of us had any kind of musical talent whatsoever; that proved our Achilles heel, unfortunately.”

Asked to assign a genre to Libido, he pauses for thought, then exhales.

“Atrocious – is that a genre? That’s the only word I can think of to describe it. The worst possible thing you could imagine.”

When his degree in media and communications finished up, Gunning spent some time travelling around the US before moving to Italy for a spell. Ireland called again but his feet had the itch by now and when a friend revealed plans for a holiday in Japan in 2000, a life-altering change of pace was about to occur.

“I came for two weeks and absolutely fell in love with the place, didn’t want to leave at all. As soon as I went home I quit my job and started applying for jobs in Japan.

“A year later I was living in Osaka and, nearly 20 years on, I’m still in Japan. A city like Tokyo, where I live now, you can never reach the end of it. There are vast sections of the city where I haven’t walked around the streets.

“It’s the contrast between the ultra modern, at times it feels like you’re living in the future, and then you have the traditional side of things – like sumo. I didn’t know anything about sumo until I came to Japan, but it was the only thing I could understand on the television because I didn’t speak Japanese when I came here.

“I got hooked on it straight away.”

Gunning had played a bit of semi-pro soccer in a tri-state league in New England, and persevered with the beautiful game when he landed in Japan. The extreme heat of the summers though, allied to aging limbs and a dodgy knee, accelerated his quest to find something new.

New and exciting, just as the amazing technicolour of American football had been back in the day, something about sumo pulled at him and wouldn’t let go.

“When you go to the tournament itself and you’ve got all the sights, sounds and smells, it’s so different from any other sport. It’s so unique,” said Gunning.

“Like, professional sumo is not just a sport, it’s a lifestyle. It’s a cross between sport and being in the military, or living in a monastery; it’s a 24 hour thing, there’s no separation. It hasn’t changed for 350 years.

“Both physically and mentally, it’s extremely taxing. Their lives are lived essentially the same as they were in the 1800s. When you go in at first, you have no rights – 95 per cent of the people in the sport don’t get any salary. Their stable-master is the ultimate authority, each stable is like a family more than a team.

“I know a Canadian guy who went in a few years ago - I was translating for him - and he asked the stable-master for the wifi code – the stable-master laughed at him. He was like ‘you’re not allowed to use the internet for the first three years, you don’t need the code, you’re not allowed to have a phone. What you can do is write a letter once a month to your family in Canada’.

“This guy was probably 20, I don’t know if he’d ever put pen to paper in his life, he’s living on Instagram, and he’s being told he can write a letter?!”

The amateur side, which Gunning joined in 2004 and participated in for 10 years, wasn’t just as brutal – but did see him double his weight from 60 to 120 kilos in a bid to reach a competitive level.

“I started at 30, the age most guys retire, and where I did a lot of running in my soccer days, that pretty much switched to all power and strength stuff.

“You don’t have to put on the kind of mass I did because in the amateur side of the game there are weight classes, where in professional sumo everyone fights everyone, but my decision to gain weight was deliberate because the lighter groups are very fast, and I didn’t have the speed.

“My style of sumo was more suited to a power style than a speed style. The more weight you have on top of the muscle, the more impact that has when you hit your opponent, and when they hit you, it’s harder to move you.”

He represented Ireland at the 2007 World Championships in Thailand, 2008 in Estonia and Hong Kong in 2012 but, by his own admission, didn’t quite do himself justice on the big stage.

“I never got the results I wanted or thought I deserved,” recalls Gunning, who commentates for NHK, Japan’s public broadcaster, alongside his day job at content director at Inside Sport Japan, a sports media agency he set up in 2017.

“I was never able to translate what I could do in training into tournaments, which was very frustrating. I lost fights to people I should never have lost to, in my own mind anyway.

“Once I lost in 2012 it was just: ‘I’m done’. I can’t keep doing this. In the big tournaments it always felt like the body couldn’t move; it was as though I was in slow motion.

“Looking back, I think I was always more focused on trying not to lose than winning. When you’re trying not to lose, you get tense and you don’t move as freely as you should. In sumo, you’re screwed if that happens.

“Every fight is over in a couple of seconds. You can’t work your way into it and come back in the second half, there’s no bad round after which you can adjust your strategy. There’s nothing. In sumo, it’s rock, scissors, paper, you throw it out and you either win or you lose.

“You spend a whole year training and then it’s over in a flash.”

And that training, even at amateur level, could take an almighty toll, with Gunning’s catalogue of catastrophic injuries telling their own tale.

“I broke teeth, fractured my skull, but my main injury was when the left humerous split up the bottom and right down to my hand. It was a throw in sumo where a 120 kilo guy just fell on the arm as it was extended and snapped it like a twig. It split lengthways, top to bottom.

“That arm had been supporting me and when it snapped my head crashed straight into the ground. I lost sight and hearing for 10 minutes I hit my head so hard.

“It took four months for the bone to start fusing back together, 18 months for them to completely fuse. I basically had a dead arm that was tied to my body for the first four months because all the nerves had been severed.

“But the thing is, I kept training. I went in after a month, black and blue, plaster of Paris cast tied to my torso and the coach looks at me and says ‘are you going to train? There’s nothing wrong with your legs, is there? Do some squats’.

“That’s the sumo mentality.”

As if the finer details of that injury aren’t enough to send the stomach into a spin, Gunning winces as he recalls some of the methods of preparation undertaken to ready himself for battle.

And that’s precisely the reason why he continues to call for some kind of head injury protocol; because he has seen, and felt, first hand exactly the kind of damage competitors are inflicting upon themselves.

“One of the things we used to do was basically ramming your head into a wooden pole. At the face off, you drive into your opponent head first, a bit like American football – only you’re not wearing a helmet.

“That kind of training still happens with kids now, the CTE and concussion issue is a ticking timebomb in sumo because it doesn’t have the rules to adjust to make it safer. It’s basically two massive people crashing into each other from a crouching position – head to head contact, with full power.

“Some of these guys are 200 kilograms and more. You hear that massive crack of the head, and we used to practice for that on a wooden pole. I thought it was toughening up the skull so you got used to the impact - 15 years later it’s like ‘what were we doing?’

“Now we know any kind of impact with the head is not good, yet I’m the only person I know who raises the issue. I talk about it a lot but the awareness is not there yet in sumo.

“If or when it does come in it’s going to be very difficult, because what do you change? What will happen eventually is what has happened to American football in the States where parents don’t want their kids doing it any more.

“Sumo is a rough fit in the modern world, there’s no getting away from that.”

What the future holds for this ancient art, nobody knows, but Gunning’s lies in Japan – “this is my home” – at the heart of a community he calls his own, despite occasional differences of opinion.

“There was definitely a gap in the market for an Irish sumo wrestler,” he smiles.

“It’s probably a bit like the Jamaican bobsleigh team. Maybe they’ll make a Cool Runnings of Irish sumo film one day.”

Hollywood could do worse.