THE old railway line that ran out behind Brian and Cautie McEniff’s home in the corner of the Holyrood Hotel carpark took as much away from Bundoran as it brought to it.

He was still a young man when the Northern Irish government decided it didn’t like the unfettered access to the Pettigo border and cut off funding. The line shut in 1957 but at least it stopped ferrying the young men away on the first leg of excavations to England and America and Australia, from which many never returned.

The town has grown up with McEniff. When the couple arrived back from Canada in 1966, Cautie had bother settling. Born on the fringes of Cork city, drawn to the lights of Toronto, she came to rest in what was then a sleepy seaside town.

It was only really when the storm hit on February 9, 1988 that Bundoran sprang to life. Content in its slumber, its people woke up that morning to find the place wrecked. Instead of rebuilding it as it was, they built it as it is now, a bustling seaside tourist destination.

The Holyrood’s carpark has room for 120-odd cars. Last Friday, there were three in it. The sun bounces off the water on the side of the road, but there’s nobody about to enjoy it.

The pandemic ripped the hotel trade to a shuddering halt. He had just signed his six hotels all away to different children in December 2019 but has stayed on as chief executive to see the crisis through.

Ten kids they raised here. Twenty-one grandchildren now brighten up their lives, sprayed across the world from Westport to Vancouver to Dubai.

The youngest, granddaughter Vanessa, bounds through the place with the energy only a four-year-old can bring.

“She brightens up the whole house,” smiles her Granda.

McEniff would nearly have classed himself as a Tyrone man for the first 15 years of his life.

His mother, Lizzie [neé Begley], was down from Carrickmore helping her uncle Barney run the local bar after his wife died.

John McEniff was passing through to visit his sister Kate on his way to emigrate to America. John met Lizzie. Nobody left.

Carrickmore was where the young Brian McEniff and his siblings spent their summers, at the farmhouse. He always had an affinity with the place and ended up twice managing the football team, although that wasn’t solely his own call.

His uncle Johnny, whose 1940 championship-winning team picture sits in the hallway with hundreds of others, landed down to see him.

“My mother came out and said ‘you’ll go to Carrickmore’. That was it.”

A strong, good-living, “extreme right-wing Catholic woman, just like Cautie”, she loved her boys at their football.

Brian missed out on the extremism but “would have been a good enough Catholic”.

He famously gave his players Garton clay, which was said to exempt you from drowning if you carried some in your pocket, and handed out miraculous medals that had been blessed at Lough Derg to his players before the ’92 All-Ireland semi-final.

Sitting in front of him is a Bundoran team photo from 1960. In it is his brother Pat, a doctor, who died in December from Covid-19. He starts to run through the names and ages of the men behind the glass.

“Jack’s 18, Pat’s 20, Peter Quinn 17, Bernie Brady 17, Brendan McHugh 18, John Martin 17, myself 17, Frankie McGlone – who ended up a professional golfer – 20, Eunan McGovern 21. That was a young team.”

They won a junior championship that year but by 1963, they couldn’t field. They joined up with neighbours Ballyshannon and would go on to dominate the fields of Donegal football, winning seven county titles between ’65 and ’76.

On a dresser in the hallway sits the aging silver of the original Ulster Club trophy from 1966, which they got to keep as it wasn’t official. They would go on to win the All-Ireland, which was in the same boat, although it would be 1975 before they won the official provincial tournament.

By then, he’d been to Canada and back.

* * * * *

THE 1974 All-Ireland semi-final against Galway was barely 15 minutes old.

Seamus Bonner had scored seven goals in Ulster – one against Tyrone, four against Antrim and two penalties against Down in the replayed Ulster final.

He had his eighth in no time, and had spun Galway full-back Jack Cosgrove again looking for a ninth.

“He was in for a second, the Galway goalkeeper came out and busted him. Cracked his ribs, he was carted off.”

Then Pauric McShea hit McEniff a ball. He took a bang as he collected it and as McEniff and the ball both fell, he put his hands out to grasp it. A stray boot came flying.

McEniff’s thumb was sliced in half, hanging together by a thread. His brother Pat, a doctor, came down from the stand in Croke Park and stitched it back together. Galway won 3-13 to 1-14.

“The boy had steel caulks which he shouldn’t have been wearing, he was obviously playing a bit of rugby as well.

“My wife would never say it but she said that day I should have gone back on. She was right. I should have gone in full-forward because they had a plug of a full-back, I could have run him blind.”

The thumb on his right hand has sat inroads since.

It was the second misfortune that curtailed a musical career he would have loved to have pursued.

“We used to have a very good singing pub. I’d do a day’s work and then I’d sit down at the piano there at half 8 at night and play until half 11.

“I’d love to have sang, but I’d have been thumping away at a piano for three hours while all the drinking was taking place.”

The inability to sing wasn’t a lack of talent, but the consequence of having gotten his tonsils out at 13 and not given his throat any rest. All the time he’d play football, he’d be engineering things on the pitch. His voice never properly returned.

It contributes to the idea that McEniff is this gentle, softly-spoken soul.

“Outside of football,” he laughs.

“My father was a very gentle sort of a person. He had a sad oul life, the fact his father died before he was born.”

His father had been born in Glasgow and brought to Ireland with an ingrained love of Celtic. They’d get the Scottish Sunday Post and Brian would devour the pages.

That encouraged a love of soccer that became a love of Sligo Rovers, where his father would take him to watch games and he’d eventually end up playing in the League of Ireland, dodging The Ban.

He would have loved to have played soccer at boarding school in Monaghan but it wasn’t allowed. McEniff would get games going on the tennis courts and the priest would come and take the ball.

The same priest would slap him for not singing at mass in the Cathedral, which he loved doing but couldn’t any longer because his voice had gone, and then dropped him from the panel of subs for a Corn na nÓg final.

“It gave me great pleasure to play for Donegal minors and beat Monaghan when he was over them. It was in Ballyshannon, I was captain, and I got great joy from it.”

* * * * *

“As Emerson said, ‘God offers to everyone his choice between truth and repose. Take which you please – you can never have both’. I want to be certain we make the choice for truth.”

- Bobby Kennedy, April 14, 1964

THREE thousand people paid $100 a plate that night to hear Bobby Kennedy speak.

At the back of the convention hall in the Royal York Hotel stood an open-mouthed, 21-year-old kitchen hand from south Donegal.

“The hair would stand on your head to hear him speak.”

Brian McEniff never shied from giving his version of the truth on any topic.

After last winter’s Ulster final in which Donegal were stunned by Cavan, he kept trying to call his young clubmate Jamie Brennan, whom he coached as a nine-year-old.

“I gave him a good lecture after that defeat. I wasn’t severe on him but I told him what needs to be done and what he was short of.

“He wasn’t responding to any phone calls because I wanted him to sell lotto for the club. I met him accidentally at his mother’s house, she’s the loveliest woman from west Sligo, mad GAA woman.

“I said ‘Jamie, I’ll give you advice, but don’t be hiding from me. Phone me up. I love you to bits and I want you to do terrible well, but you have to get advice.’”

Brian and Cautie had chosen Canada above America because there was no army conscription. They’d chosen it over Australia because, even though the £10 assisted fare was affordable, it was simply closer.

And they chose it over Switzerland because other boys had come back from there to college and reported being “treated like shite because they thought we were English, all they were doing was polishing door handles”.

He would work from 8.20am until half 4 in the afternoon, and then sprint across the road to the North American Life Insurance Company, where he’d clock in – “always a couple of minutes late” – and work until 12.30am.

In between, he tried to fit in some semi-professional soccer for an Italian club that was giving him $75-a-week at a time when the money in England was £20.

But something had to give so he came down a grade in soccer. He’d also got stuck straight into the GAA club and, although he’d always led from the front with Bundoran in the era before managers, this was his first real taste of it.

He became secretary and then started to run the team. He’d two big Cork men who did a lot of damage for him, and they played on the agreement that McEniff would hurl for them – which he did, winning two championship medals at corner-forward.

The football team played in the Mid-West League. Half of the team from the year before had gone to San Francisco and it took three years to rebuild.

They had just beaten Cleveland and were qualified for the final when the call came from home.

“My father took a stroke. That was that.

“I got a call to come home within a couple of months. The second call was to come within a week. The third call was to come right away.

“I came into Dublin, my brother Sean had a dark-coloured tie on so I assumed he was dead. But the doctors were fit to manage him. He made a good recovery and it gave him some time.”

In that time, McEniff took over running the hotel business. He was brought down to meet his father’s solicitor and told he had “responsibilities”, and that county football couldn’t be one of them.

“So I made a commitment to my father that I’d stop playing county football.”

Soon after his father passed away, he was down to watch Sligo Rovers play Dundalk – “it was a great game, Sligo beat them 6-5” – when he was asked if he’d tog out for Donegal for a game in Sligo.

“My father had died and my mother wasn’t going to stop me playing football. It kept me f***ing half sane.”

His father had “taken a reasonably good drink and a smoke”, and the ill-health that led him to was part of why Brian McEniff has been a lifelong pioneer.

There was also the impact of Owen McGuinness, “a great man who taught us everything that was good” while he was at school in Monaghan.

And there was music, which he was far more interested in than drinking.

“There was wile drinking at that time. Jesus, wile drinking.”

In different circles, though. When St Joseph’s won a county title, he never went celebrating. Thirteen of the fifteen men who started their first county final in ’65 were pioneers.

It took time to establish himself with the county but his razor sharpness found a home in the number five jersey.

By 1972, he’d had two years as minor manager, been sacked and then taken over the seniors while still playing, taken them to a first ever Ulster title and won the county’s first Allstar himself.

* * * * *

“I GOT sacked a lot.”

In a GAA lifetime as fulfilled as his, there were bound to be downs to go with the ups.

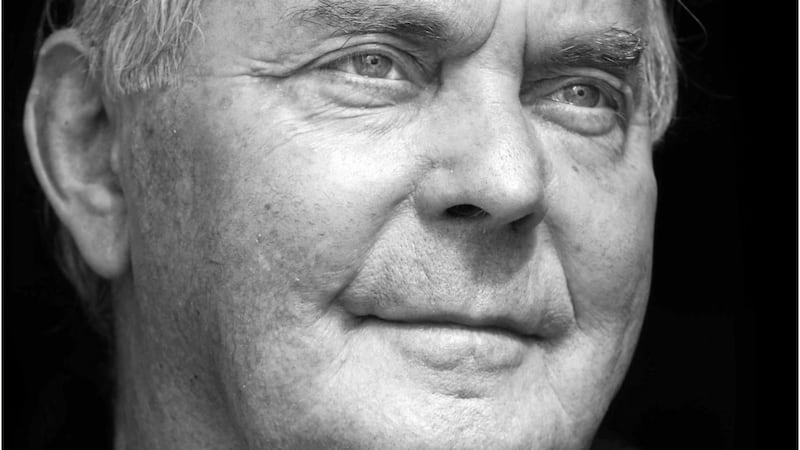

Now 78, McEniff has given 60-plus years of unbroken service. He was Donegal manager five times, minor manager twice, Central Council delegate, county chairman, player, referee, administrator, the lot. Not to mention his 25-year spell in charge of Ulster’s Railway Cup team.

Donegal had won five Ulster titles until 2011, and he was manager of all five teams across three different spells. He was chairman of the committee that gave Jim McGuinness the U21 job, so you could argue he had a hand there too.

Right now, he’s Bundoran’s chairman again. His last managerial involvement was with an U14 ‘B’ team.

“We won a shield and it was as good as anything.

“At the minute they’re talking about amalgamating with Ballintra or Ballyshannon, and I don’t want that. I want no player to be left out.

“If I have to work this year, I’ll work with the U17s. I don’t want to do it but I’ll do it if I have to.”

That’s been a theme, never less than when he reassumed the senior reins in Donegal for the final time in 2003. He was county chairman and having been tasked with finding a new manager, he couldn’t and ended up doing the job himself.

There’s no doubting he liked the feeling of being in control. Better to be telling men what to do from inside the tent than pissing into the wind outside it.

Managing the 1992 All-Ireland winning team was the ultimate fulfilment.

Donegal had never won an Ulster title before 1972. He recalls how he “hit the door a f***ing kick” just before they went out for the All-Ireland semi-final against Offaly after a defeatist comment from one of his team-mates.

“He turned to Pauric [McShea] and said ‘Pauric, you’ll keep out the goals today’. I said ‘there’ll be no f***ing goals’. There were lads on the team that no matter what I did, they just didn’t believe.”

They won Ulster again in ’74 but trouble reached paradise when they were brought out to New York by John Kerry O’Donnell.

“We landed out and he had these big posters up all around the Bronx. First day out, New York v Donegal, great. The second day, New York Youths v Donegal Selection.

“Then the New York championship final, Donegal New York v Kerry New York. I was playing for Kerry.

“Got man of the match, the winning goal.

“Came back home, P45.”

He went back in 1980, won Ulster again in ’83, took them from Division Four to Two. Sacked again, and Tom Conahan took over.

“In fairness, Tom Conahan had won an Ulster and All-Ireland U21 and was entitled to his run.

“They were beaten in the Ulster final in ’89 and I knew at that stage I’d like to go back. So I went against Tom. I’d have been friendly with him but I wanted to win an All-Ireland before I was 50.”

Brian McEniff was 49 years and nine months when The Hills of Donegal rang out through Croke Park.

A county that so lacked for the self-belief that he implored them to discover found itself among the sporting Gods, able to stick their chests out and be as proud of Donegal as he’d always been.

By the time it all ended in 1994, the shine had been lost. Things happened, words were said, but all the relationships bar one survived.

“I love those boys still. You’ve no idea how close I got to those boys. On Christmas Day in ’92, I phoned every one of them.

“During the lock-up, I phoned every one of them again. Except McHugh.”