RUMOURS had bubbled around the streets of Dublin all morning. Was Stephen Rochford actually about to drop David Clarke and replace him with Rob Hennelly?

The 2016 All-Ireland final replay will forever be remembered for that bold tactical move which, as it happened, went horribly wrong for Mayo.

Hennelly would endure a difficult afternoon capped when he spilled a routine ball at Paddy Andrews’ feet, forced to drag him down for the decisive penalty and his own black card four minutes into the second half.

David Clarke would end the game with a bullish, angered display and finish the year as the Allstar goalkeeper. He'd lost his place off a poor finish as Dublin overwhelmed Mayo's kickout to grab a draw.

When Clarke is in goal for Mayo, they have the best shot-stopper in the country behind them. They have a fearlessly brave goalkeeper who, as he displayed on Sunday, has a command of his square that gives those in front confidence.

Mayo look a more assured defensive unit when he plays. Their players appear to have greater trust in him than in Hennelly.

Rochford wasn’t completely crazy though.

The logic behind that call four years ago remains true to this day, and in as much as the win over Tipperary can be analysed, there were two primary concerns.

One was the number of goal chances Tipp created. The second was their origin.

Three of Tipperary’s six second half goal chances came off David Clarke’s kickouts. A fourth was as a result of his failure to pick up a routine ball, with Michael Quinlivan screwing his shot wide on the turn.

Dublin are so good at creating goal chances when they win the opposition’s kickout.

It has, heading into the All-Ireland final, reopened the long-running debate over who the best man is for Mayo’s number one jersey.

At one stage towards the hour mark on Sunday, Mayo had won just 4 of their 11 kickouts (36 per cent) in the second half on Sunday.

Between Colin O’Riordan, Steven O’Brien and Conal Kennedy, the blue shirts had squeezed up and hemmed them in.

It bore remarkable similarities to the way in which Dublin took command of last year’s semi-final with their insatiable appetite to get after the Mayo kickout after half-time.

On that occasion, Hennelly was the goalkeeper.

Dublin went from two points down at the break to leading by 2-11 to 0-8 inside ten minutes. It was a remarkable spell around which the legend has grown that Mayo simply couldn’t get out.

Yet of the first nine Mayo kickouts in the second half, Mayo won five and Dublin won four.

The difference in the teams was not that Rob Hennelly couldn’t find a green and red shirt. It was that Mayo missed five very scoreable shots in the same period.

From the four Mayo kickouts that Dublin won, they scored three points.

They also scored two brilliant goals of their own making, and the game was dead.

Hennelly had started the game nervously, just as he had that replay in 2016. He has struggled in the heat of those games, undoubtedly not aided by the fact the 2016 call placed the spotlight firmly on his head.

The same would be the case if James Horan was to repeat the decision, barring the fact that this is a very different All-Ireland final. There will be no packed Hill 16 at his back, clambering to pressurise his every kick.

If ever there was a decider that would allow for tranquillity and a clear head, this is it. The pressure element within the stadium is massively reduced.

Clarke has not been immune to it. In the 2017 final, the game was level. His second last kick hung for an age before James McCarthy won it, and Diarmuid Connolly came off it to win the free for Dean Rock to win the game.

Under enormous time pressure, his final kick sliced off the outside of his boot and out for a sideline ball, giving Dublin the ball. They didn’t relinquish it.

Back to last year. Hennelly’s first kickout of the game was a poor one. His third was worse. Mannion scored. But from there, he did very little wrong.

The stats say Mayo won just 59 per cent of their own ball. Those two early kickouts aside, it’s hard to lay much of it at Hennelly. He hit his target with all but two more for the rest of the game.

There was variation on his kicks but he hit Aidan O’Shea as often as he could. The fact that Mayo don’t currently have any other reliable source of primary possession is not on Hennelly.

Mayo do not have a Cluxton. And for years they were able to manufacture their way out of danger through a high-risk, high-energy strategy.

Clarke would poke the ball to the closest defender, no matter the pressure on his back, and that defender would shovel it back to him. That created the spare man and got them out.

It was Russian Roulette stuff but they made it work.

They only lost three kickouts in the whole game in 2017 – the first one, and the last two. Cluxton lost more.

Across the 70 minutes, they used their get-out clause of going back to Clarke five times.

In the second half, Mayo had 14 kickouts. They went short on eight.

The rule change to abolish that backpass to the goalkeeper has worked against them. You don’t see that same movement from Mayo defenders now because the risk of being isolated, turned over and taken for a goal is much greater.

The big difference between then and now was what they were kicking into. Seamus O’Shea and Tom Parsons in the middle, Aidan O’Shea at centre-forward, Donal Vaughan at centre-back. Physically capable of matching Dublin.

Parsons only came on late last year but Seamus O’Shea was still in the team, while Colm Boyle was outstanding at six.

This year, they don’t have near the same physical presence in the middle.

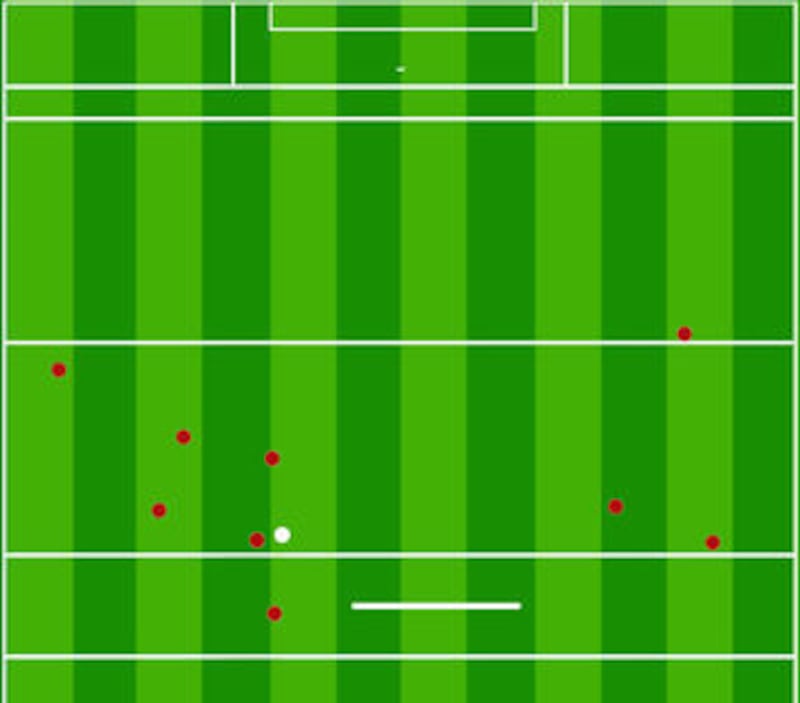

Against Tipperary, Clarke went long ten times. Mayo won just one.

When he goes long, the trajectory of the kick is much higher and loopier. That suits the opposition midfielders coming on to it to break it. Mayo’s midfielders are sitting ducks waiting for it to come out of the sky.

Hennelly’s kicks fly at a lower, flatter trajectory. They reach their target quicker and give Mayo a better chance of success on their own ball.

The risk of putting him in again and bringing the same cavalcade of noise and external pressure on Hennelly is enormous. If James Horan went for it, it would be even more magnified than Rochford’s call.

If it went wrong again, unfair as it might be, Horan’s job would be nearly untenable. People would say the warning was there and how could he make the same mistake twice.

But with Seamus O’Shea and Tom Parsons not really in the team and no real natural ball-winners beyond Aidan O’Shea on the field, Mayo have to do something.

Don’t rule out Hennelly getting the nod again.