“Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.”

Winston Churchill

A THOROUGHLY depressing Saturday spent developing a new understanding of the phrase ‘GAA politician’ was the latest example of just how broken democracy is.

Congress voting against the wishes of the people that are actually directly affected by the decisions they made was a problem not exactly unique to the GAA.

We haven’t had to look too far lately. Brexit was the perfect example.

As a comparison, take the Northern Ireland electorate as the players and Britain as the administrators.

Fifty-six per cent of voters in Northern Ireland voted to stay in the EU. In the Foyle constituency, for example, 78 per cent were in the Remain camp.

I’m almost ashamed to admit it now but I was among the 38 per cent of the population here that didn’t bother to turn out and vote.

In my defence, I was out of the country at the time, and I despise politics (which was another reason Congress and I didn’t agree).

All in, across the whole of the UK, almost 28 per cent of us didn’t vote.

But man how we wailed when we woke that morning last June and discovered ‘they’ had voted us all out of the EU.

Same with The Donald in the United States. For example, Barack Obama won Michigan in 2012 by 450,000 votes. This time around, it should have been Clinton territory, but she lost having received fully 300,000 fewer votes than the now-departed president had.

In Wayne County, Clinton lost more than 75,000 votes. They didn’t transfer to Trump, who gained just 10,000 more than Mitt Romney had in 2012. Those people simply didn’t vote.

That’s the trouble with liberals. They assume everything’s going to be ok until it’s not, and then it’s too late.

The GAA is absolutely loaded with folk of that mind. The players are at the very head of the queue.

Congress frustrated the absolute life out of me at the weekend. It was my first visit to the annual event and I will plead for each of the next 364 days that the fate does not befall me again next year.

I’d been plenty warned about how dull it can be. That didn’t bother me in the slightest.

What did bother me was how the place carried such an unashamedly political air.

For months I have been vehemently against the proposals for the round-robin quarter-final. Not because of the extra games. If it was up to me, the top 12 teams would be the only ones competing for Sam Maguire.

It’s madness that, as my colleague Kenny Archer expertly pointed out last week, eight counties have never reached an All-Ireland quarter-final, yet continue to be allowed to hold up the summer waiting for their inevitable exit.

A tiered Championship is the only way forward as part of a completely restructured calendar.

But the democratic body that is Congress won’t accept that.

That’s because those eight counties, with the support of only a couple of others, have enough of a say to stop a motion reaching the third-thirds majority (or even 60 per cent from next year) that it requires.

If you asked every team in League One of the English soccer pyramid if they would rather pack out their stadiums and expose their players to Manchester United and Liverpool and Arsenal every week end, they’d rip the hand off you.

But that’s why most sensible sporting competitions have different levels.

You couldn’t turn up and enter the Australian Open just because you own a racquet.

Yet we let counties compete for the All-Ireland despite having shown no sign that they can actually do so.

The National League is unquestionably a better competition now, by miles. February to April is when the best of the inter-county season happens.

But when Páraic Duffy brought the motion last year to allow the bottom counties to play in their provincial Championships, but not offer them a run at the Qualifiers that will amount to nothing anyway, he had to withdraw it before it got hammered.

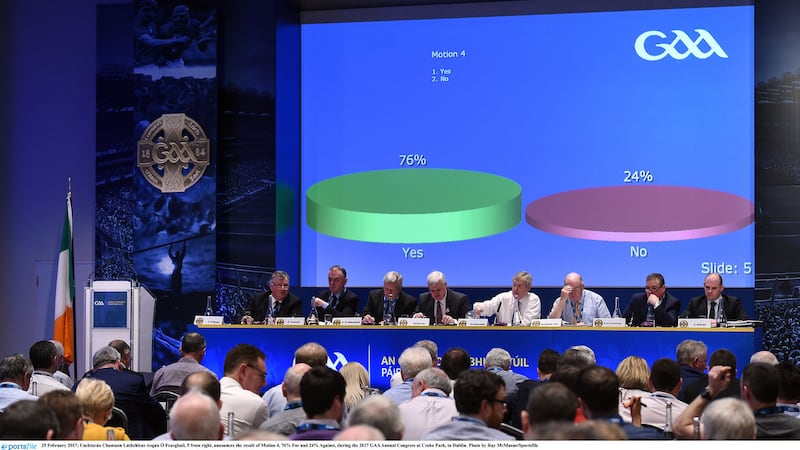

When the ‘Super 8’ motion went through, social media exploded. Johnny Magee, former Dublin footballer and now Wicklow manager, called for an all-out strike from players.

Dermot Earley didn’t exactly back that call and, in his much more measured way, he spoke of his disappointment at how scarcely involved players were in the consultation process.

The GPA, despite eventually coming out against the idea, deserve criticism for what was really faux opposition. Their plea that the players’ wishes carries no weight when they didn’t announce what the players wanted until after many counties were already mandated.

Spending yesterday afternoon in Garvaghey with Tyrone’s Ronan McNamee and Monaghan’s Fintan Kelly was hugely revealing.

Both incredibly revealed that they hadn’t voted on the proposals either way, with McNamee admitting he felt wholly uninformed about the implications of the vote.

Counties themselves are partly to blame. How many actually studied the impacts on their club calendar? That is what a responsible and efficient county board would have done.

They’re appointed to protect their clubs and the huge number that voted in favour of introducing the round robin system are guilty, at best, of not doing their homework. At worst, they neglected their clubs in favour of financial recompense.

That is where the disconnect between players and administrators lies.

The chain came off that particular bike a long time ago.

I don’t even know who my club’s county board delegate is. I don’t know if anyone from the club attends county board meetings. I don’t know what they would say if they did.

I’d hazard an educated guess that 99 per cent of club players are in the same boat.

Club players are not consulted on anything to do with Congress. Club delegates turn up to county board meetings to represent the views of their club but that is not what happens.

To give you a perfect example, club delegates in Derry were asked two years running whether they wanted to retain the back-door format of the Championship or revert to the traditional straight knock-out.

They voted overwhelmingly for the status quo, twice.

Then a Games Review Committee was formed at the end of 2015 and actually brought players and team management to meetings. The result was an almost unanimous decision to go back to knock-out.

The same thing happened at the weekend. A lot of the counties that voted on the reform proposals were mandated by their clubs which way to vote.

But Congress is only fooling itself if it believes they’re representing the views of players.

And the manner in which they go about it is what creates the anger and resentment.

There’s a triumphalism and an arrogance about it in many quarters.

Delegates declaring that there’s no need for a Club Players’ Association because the GAA represents players, when the actions a few hours previously showed the exact opposite, was particularly hard to stomach.

The GAA may be a democracy, but it’s a broken one. If Congress doesn’t change, nothing else will.