IN TEAMS littered with star names, it was the late Joe Lennon who set the bar.

He might not have had the swagger of Paddy Doherty, the long-legged stride of Colm McAlarney or the killer instincts of Sean O’Neill, but his importance to those famed Down sides of the 1960s was just as great.

Lennon passed away on Wednesday, and tributes have been flooding in for a man who made a huge contribution to the GAA not just in Down, but to the association as a whole.

Alongside Jarlath Carey, he stoked the fires of the midfield engine-room as the Mourne County famously brought Sam Maguire back across the border for the first time in 1960, before repeating the dose a year later.

The Aghaderg man, who was born in the county Armagh village of Poyntzpass, had been redeployed to left half-back by the time 1968 came around, captain and elder statesmen on a new-look team emboldened with youthful endeavour.

He led his troops all the way to the steps of the Hogan Stand - the image of Lennon wearing a smile from ear to ear, Sam raised in the air, among the most iconic in the county’s history.

Sean O’Neill remembers that day well, and the rest. Along with Paddy ‘Mo’ and Dan McCartan, he soldiered beside Lennon throughout that whole glorious era, and recalls a man whose focus was always on one thing and one thing only - winning.

“Joe did all he could to get the very best out of himself, that was just the kind of man he was,” said the six-time Allstar.

“He set very high standards, and he would settle for nothing less from those around him. Really, he set the standard for those Down teams in terms of his focus and determination.

“Any young players coming on to the panel quickly realised that Joe was to be listened to – he was quick to make sure things were done properly.”

Rampaging midfielder McAlarney is in full agreement. He was one of those young men who had come in off the Down minor side into a team that found itself moving through the gears as 1968 progressed.

Playing alongside the likes of Joe Lennon was something he could only have dreamed of when he joined in the county-wide celebrations eight years previous.

“Joe was like a patriarchal figure to that group,” said McAlarney.

“We were young players coming in sharing a dressing room with our heroes from when we were children. I was 12 when Down made that historic breakthrough in 1960 so all those players, the trailblazers as I call them, were our heroes.

“That team was a perfect blend of youth and experience. Sadly this year we have lost two of those men from both ends of the spectrum - Brendan Sloan would have been one of the younger members of that team, sadly he died early earlier this year, and now Joe.

“You’re not aware of it when you’re playing but there’s a special bond that develops amongst players on any successful side, and that is life-long. There’s huge respect there and genuine affection. You become a band of brothers.”

A champion on the field, Joe Lennon also broke new ground off it. Long before Joe Brolly and Pat Spillane graced The Sunday Game sofa, Lennon was sat in the RTÉ studio with Michael Lyster dissecting the day’s action.

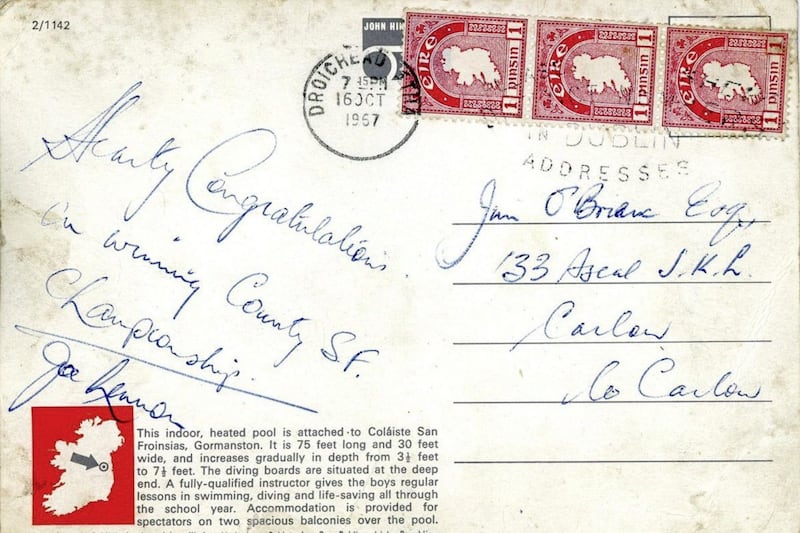

Even while still in his playing pomp, Lennon was ahead of his time, penning his book Coaching Gaelic Football for Champions in 1964. Around the same time, he also launched the first national coaching courses in Gormanstown College, county Meath, where over 30 counties were represented.

This was seen by most as a major breakthrough in the history of the game, with aspiring coaches - including future legends like Mick O’Dwyer and Kevin Heffernan - attending these courses to learn from Lennon’s techniques.

“Joe was a very deep thinker on the game,” added O’Neill.

“Sometimes, he could be outspoken - if there was something he wanted to get across, he would just come out with it. That was the kind of character Joe was, very single-minded.

“You have to remember as well that Joe attended Loughborough University, which was and still is one of the foremost sports science and physical education institutions in the world. In many respects, he was way ahead of his time.”

That attention to detail was evident in 1968 when, even though approaching his mid-30s, Lennon remained one of the fittest men on the Down team.

He had his own ideas on how the game should be played and, as McAlarney recalls, wasn’t behind the door when it came to bringing team-mates into line when required.

“Joe was a fearsome competitor and he expected that from everybody,” he said.

“I remember in the All-Ireland final when I was coming weaving out with the ball around the half-back line. I loved to carry the ball but Joe would have been more direct.

“I had ridden a couple of heavy tackles and was contemplating whether to go on, until I got a verbal bullet from Joe - ‘kick the ball you bloody eejit!’ You definitely did what you were told.”

Many often wondered if his depth of knowledge would transfer to the managerial stage and, in the early 1980s, those questions were answered when he took on the Down job.

The result was an Ulster title in 1981, beating Armagh before the Mourne men fell to Offaly in the All-Ireland semi-final. In 1982, Down were edged out of Ulster by Tyrone at Páirc Esler and, like that, Lennon was gone from the post, never to return.

Despite his fearsome reputation on the pitch, those who played under him remember a different personality in the changing room: “Joe was a lovely man with a great knowledge of the game,” said Tommy McGovern, Lennon’s captain as the red-and-black landed the Anglo-Celt Cup 35 years ago.

“He was a calm person under pressure, a cool sort of a customer. I always remember the story that after one of the All-Ireland wins he just left Croke Park and went to Dublin airport and got a flight back to England. You wouldn’t see that happen today.

“Joe was a man I had looked up to, one of those who won three All-Irelands. Everybody had great respect for him and all that he achieved. It’s a sad loss for the county.”