SITTING on a train heading down the east coast of Australia in the late spring of 2004, Colm Bradley decided it was time to return to the motherland.

The four-hour return commute to work each day, to stand all day with a wacker plate and come home with the minimum wage, wasn’t fulfilling the dream.

The Fermanagh forward wasn’t due home until May, but even though he came back early, it wasn’t for football. The clan at home had organised a 60th birthday party for his mother in April.

“The travelling was done, the craic was had, and I thought ‘I could be at home working rather than out here’,” he recalls.

So with $20 to spend – with which he bought a Burger King in South Korea and another in London – and an unspent cheque in his pocket for a month’s work to a Sligo man, it was back to Enniskillen.

Tom Brewster came too. Ronan McCabe, though, decided to head on to America and see a bit more of the world.

The three of them had headed off with another clubmate just after Christmas 2003, disillusioned. Enniskillen Gaels’ sixth consecutive county title had brought them no closer to the Ulster glory they craved.

After provincial final defeats by Crossmaglen (1999) and Errigal Ciaran (2002), they looked a jaded side as St. Gall’s ended their 2003 hopes at the quarter-final stage with more comfort than the two-point margin suggested.

“I’ll be honest, I was just sick of football. I wanted a break from it. Me and the other two boys had always wanted to go travelling.”

Things had taken a worrying turn for Fermanagh as well. A county with as little success as they’ve had might have been delighted with reaching a Division One semi-final and an All-Ireland quarter-final in 2003.

But the manner of their defeats by Tyrone in both left a strong aftertaste. There were nine points to separate them in the League game, but by August, the chasm had grown to 19.

“I was only 23 and it hit me hard. We’d worked so hard to be dismantled as we were in the All-Ireland quarter-final. It was 1-21 to 0-5 or something. To be truthful, it could have been 3-30.”

Tyrone spent the winter celebrating their first All-Ireland while Dom Corrigan slipped quietly out of the Fermanagh hotseat. Charlie Mulgrew was appointed and began contemplating how to reconstruct Fermanagh’s shattered confidence.

It had been their first year without Rory Gallagher, and the season’s end brought the retirement of his cousin Raymie - who had captained them in ’03 – and Paul Brewster.

Work commitments ruled out Neil Cox and Mickey Lilley for 2004, and it looked a big ask for a group of youngsters like Eamon Maguire, Mark Little and Niall Bogue to step in as instant replacements.

By the time the Enniskillen trio stepped aboard the tin bird, they knew their Ulster Championship fate: a quarter-final with the reigning All-Ireland champions, the Tyrone side that had crushed their dreams so viciously.

Australia was just about far enough away. But his seven-a-side exploits in the sunshine dented Bradley’s confidence further.

“The three boys played reasonably, but I couldn’t even run. I was so bad it was incredible.

“When I came back, I was in two minds whether I’d go back to the county at all. But at the same time when you’re at home, you’re 23 or 24, and I always loved playing for Fermanagh…”

So back he went. Little did he know that four months later, Fermanagh would still be standing when Tyrone had gone, and that they would be twice within moments of reaching an All-Ireland final themselves.

Instinctive memory suggests that it had come from nowhere. The fact that they’d gone from 1983 until 1999 beating only Antrim in the Ulster Championship fires weight at that theory.

But it didn’t. Take their encounters with Mayo as the prime example. Fermanagh had knocked the westerners out of the Championship in 2003, having already beaten them in a crucial League game in Charlestown earlier that year.

Fermanagh had also beaten them in Brewster Park the previous year and while they did lose the other three meetings between 2004 and 2007, there was only two points in it on each occasion.

They drew with Dublin in 2004, and in 2006, they overcame both the Dubs and Tyrone in the National League. These were the top teams in the country, and Fermanagh were right among them.

“It’s very easy to look at one year and think it was a fluke, but we beat a lot of good teams over a four- or five-year period,” says Bradley.

“We don’t even want credit, but ourselves, we’d be happy enough.

“For four or five years, nobody could argue that we were a top-12 team. Some of those years, we were top-10, top-eight. From where we’d come from, that was progress.”

IN four years, Charlie Mulgrew only lost to Tyrone or Armagh in Ulster.

It was the Red Hands, by a 1-13 to 0-12 margin, who ended their provincial hopes in 2004, but Fermanagh would outlast them that summer.

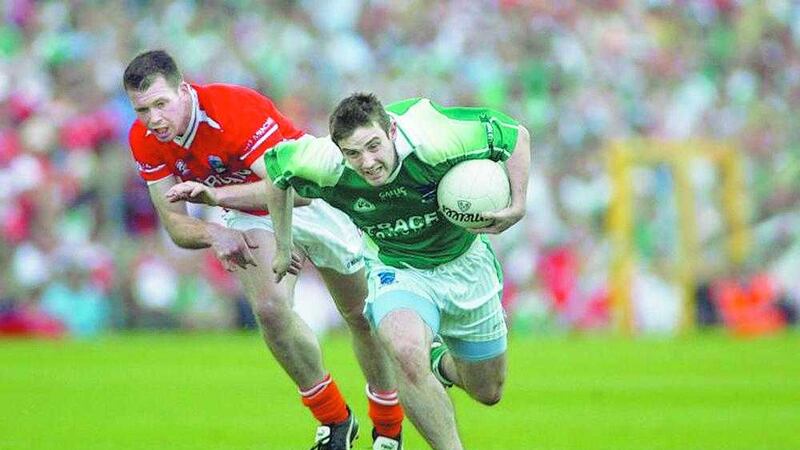

A walkover against Tipperary was followed by extra-time victories over Meath and Donegal, sandwiching a comprehensive dismissal of a one-dimensional Cork side.

The measure of that result was that it was Fermanagh’s first ever senior football victory in Croke Park.

Their second will always be remembered. Armagh were once more Ulster champions, winners of the All-Ireland in 2002 and runners-up the following year.

The bookies were offering 1/6 on Joe Kernan’s side, but Tom Brewster had other ideas. Having been injured at the start of the Championship campaign, he was struggling to force his way into the starting line-up.

There were only three points scored in the final 22 minutes, but the excitement and chaos of that spell was like nothing you will ever see again as Brewster kicked the last two scores to settle it in sensational fashion.

The same afternoon, Tyrone lost their All-Ireland title. Mayo clipped their wings. Suddenly the path was cleared.

IT poured from the heavens all day. Hill 16 remained deserted amid its refurbishment, but each of the 64,500 seats were taken on August 22.

It ought to have been Fermanagh’s day. James Gill was sent off for Mayo early in the second half. The momentum was driving relentlessly into the Canal End, the ball coming in on top of Fermanagh’s forwards for much of the last 20 minutes.

But, with glory beckoning, the wide count rose. Too many wides.

Tom Brewster has one last chance, from almost the exact spot he’d kicked the winner against Armagh. It hangs for an age but comes down just short. Another draw. No extra-time this time.

“We didn’t really know how to use the spare man that day. It was the first time that year we’d dealt with a spare man for any period of time,” says Bradley, who hit four points and tormented Mayo.

“If you win a game by a point and you miss a bagful, nobody ever really talks about it. The quarter-final against Armagh was 0-12 to 0-11, and we probably created 25 or 26 scoring chances.

“We were creating a lot, even against Armagh, and we didn’t take them either. But nobody remembers that because you got over the line.”

Times were such that Fermanagh hopped straight on the bus, despite knowing they had just six days until the replay. Mark Little, a bricklayer, was back on the building site the next morning.

“That’s nobody’s fault, like. We didn’t think anything of it at the time,” recalls Bradley.

“But looking back now, can you imagine a team playing an All-Ireland semi-final and drawing, and knowing they were playing again in six days’ time?

“They’d probably all stay in Dublin and have a pool session in the morning, and look at the tape of the game. They just wouldn’t go to work.

“Six days was a short turnaround and we’d had a lot of games that year in a short period of time, because we’d gone through the back door.

“And we had extra-time twice. Not that it bothered us. But they were probably the fresher team the second day, and it took us a good 20 or 25 minutes to get going in that game.”

They got off to a poor start in the replay. Four down in no time.

The changes came to the fore. Charlie Mulgrew had decided to shake things up and finally started Tom Brewster. Nobody expected that it would be James Sherry who would be dropped, though.

He was introduced after the sticky first 25 minutes and almost instantly hit the net to spark Fermanagh into life.

Equally important was Mayo’s attacking rejig. They pushed Ciaran McDonald closer to goal and out of the clutches of Niall Bogue, who had been one of the stars of the run and dominated their battle in the drawn game.

The Crossmolina genius got a bit more space in the replay and made use of it.

And yet, Fermanagh clawed their way right back into the game and with five minutes to play, they had one foot in the final. They led by 1-8 to 0-10.

But they could hold on no longer. Conor and Trevor Mortimer swung the lead back in Mayo’s favour and Austin O’Malley sealed it at the death.

“Ah, there’d be a huge amount of regret,” admits Bradley.

“We played seven Championship games that year and by far and away our two worst performances were against Mayo. It was disappointing from that respect.

“We never really got going in attack either day. Not too many of us scored from play. Nine points isn’t really a good return, though conditions were terrible the first day.

“The second day, we played for about 20 minutes before half-time and after half-time. We played really well and got ourselves in a position, but we just didn’t see it out. It was disappointing because we’d played much better in previous games.

“We really felt we were going to make the All-Ireland final. It was hard to take.”

Mayo went on to start the final well against Kerry, an early Alan Dillon goal giving wind their ambitions of breaking the curse, but it quickly fell apart.

Colm Bradley isn’t naïve enough to suggest that Fermanagh would have won the All-Ireland, but he feels their ruggedness would have provided a greater test for the Kingdom.

“This is no disrespect to Mayo, but I always found playing that Mayo were very clean. They didn’t pull and drag you.

“I’d go out as a corner-forward against Mayo and for 70 minutes, you wouldn’t be touched.

“They were an incredibly clean team. Good footballers, don’t get me wrong. Gary Ruane in particular, I remember he kept Peter Canavan pretty quiet in the quarter-final when he came on.

“He marked me in the replay, and was a real good footballer.

“But their defenders as a whole, they wouldn’t have been physical. I’m not saying our boys were into the dark arts, but we lived in Ulster.

“It’s just a different game. We played Donegal, Tyrone and Armagh that year, three Ulster teams. As a corner-forward, you were getting far more attention.”

And as much as the semi-final defeat hurts, it’s missing out on what would have been the county’s first Ulster title that still really sticks in Colm Bradley’s throat.

“We were good enough to win one, but we didn’t. That’s probably as big a regret, if not bigger, than the semi-final.”