AN UNMARKED grave in Wimbledon. No headstone, no flowers (maybe there never were), no candle kept alight in memory of the man who lies six feet down beneath the unkempt turf.

This humble plot at Gap Road Cemetery is the final resting place of Thomas Cusack from Carron, county Clare - born 1852, died 1933 at the age of 81.

Thomas might have played unorganised Gaelic games with his elder brothers in his early days but, as he neared adulthood, there was no time for sport in the impoverished west of Ireland. Along with his sister and two of his three brothers, Thomas left these shores to seek his fortune, but one Cusack stayed at home - his name was Michael, Michael Cusack, and he went on to found the Gaelic Athletic Association.

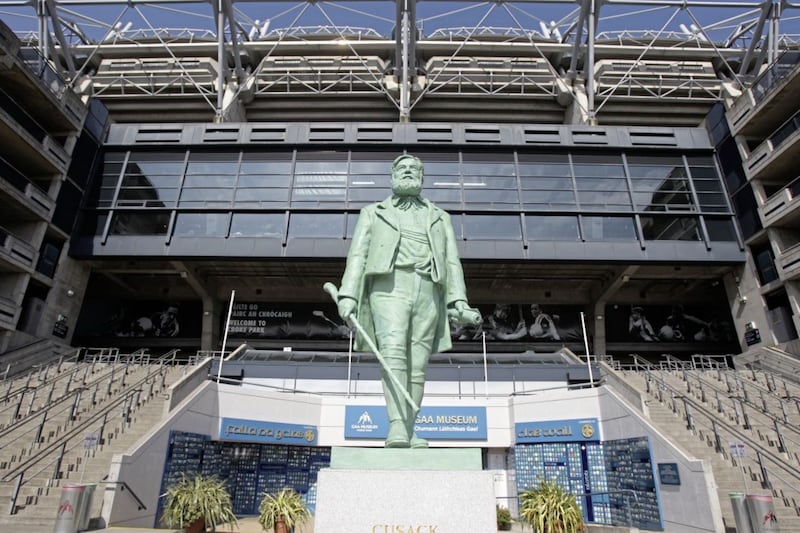

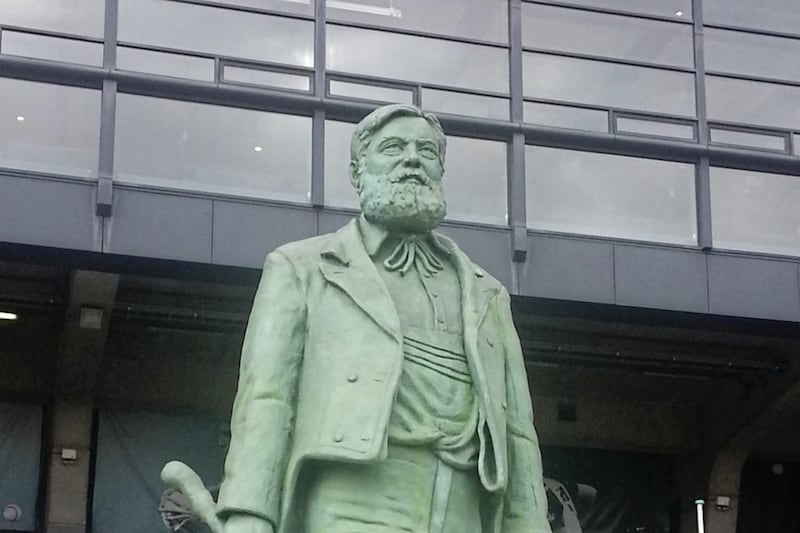

Six years before Thomas died in 1933, the Cusack Stand was opened at Croke Park in memory of his brother. He may not even have known about it because Michael Cusack died in 1906 and all contact with his siblings was lost.

GAA historian and genealogist Michael Anderson was the first person to trace Thomas’ faint footprints from Clare, through Wales to his final resting place. Michael and his daughter Maria visited his graveside and said a quiet prayer - they were probably the first people to stand there since his funeral in 1933 because Thomas never married and had no one in Wimbledon to mourn his passing.

Today, the Cusack Stand at Croke Park is a 27,000-capacity facility and Michael Cusack’s name has been immortalised by the GAA - his statue welcomes patrons as they enter the Cusack Stand and there are grounds and clubs named after him in Ireland and around the world. But his contribution to the GAA seem to have been lost on his sister and his brothers and, sadly, his family name has long since died out in Ireland.

Michael Cusack carved out a successful teaching career that included three years at St Colman’s College, Newry, but poverty scattered the others to the four winds - his sister Mary and eldest brother John emigrated to Australia, Patrick went to Brooklyn, New York, while Thomas ended up in Wimbledon. Apart from Thomas, all of Michael’s siblings married and had children, but their descendants knew nothing of their family's link to the GAA because no-one had been able to trace any of them - until Michael Anderson began his painstaking search and found all four.

His work began in 2008 when he was asked to look into the history of the Woods family in Dromore. The county Down market town isn’t known for its GAA connections, but Michael Cusack’s wife Margaret Imelda Woods was born and bred there. Down county board official Fintan Mussen approached Michael to research Michael Cusack’s connection to the Mourne county as part of Down’s celebrations to mark the 125th anniversary of the GAA.

“Michael Cusack had married Margaret Imelda Woods from Dromore but, beyond that, nobody knew anything about the Woods family,” Michael explained.

“Fintan thought it would be nice to find out what sort of a family she came from, where they lived in Dromore and what happened to them and if there were some relatives still around. I was asked to find that out and give a talk in 2009 as part of Down’s 125th anniversary celebrations.”

Michael fulfilled his brief and did presentations for the Down county board, the Ulster Council and a local history society and his findings were published in the Down Year Book in 2009 and in the Seancas Ard Maca (the journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society). It soon became apparent he had uncovered a door that opened on an even greater challenge

“The one question that kept coming up when I did those talks was: ‘What about Michael Cusack? Did he have any brothers or sisters?’,” Michael recalled.

“The only thing that was known was that he had three brothers and a sister - his brother John and sister Mary went to Australia and that one of his other brothers, Thomas or Patrick, went to Wales. The reason that was known was because there was a note Michael had written saying: ‘just returned from visiting my brother in Wales’. It didn’t say which one and nobody knew where the other brother had gone.”

Michael spent countless hours sifting through census records, military records, registers of births, deaths and marriages and old newspapers. Gradually, he unearthed layer upon layer of the family over the course of the last six years

He started by tracing Mary and John in Australia and tracked them both down. Mary had settled in Sydney and married Edward Fahey. Her daughter Mary Matilda Fahey’s second marriage was to Charles Butcher and Michael was able to get in touch with his grandson Peter Buchanan through a newspaper article.

“Peter was a cricket fan who had never heard of the GAA,” he explained.

“There is a GAA club in Sydney called Michael Cusack’s - it’s named after his great great-uncle, but he had no knowledge of it. Last year, my daughter got married and went to Australia on honeymoon, he emailed me to say he’d like to meet her. Before they went, I got in touch with Croke Park and they wrote a letter of greetings inviting Peter and his wife to Croke Park and they were thrilled to receive it. I sent him pictures of Croke Park and the Cusack Stand and he was stunned.”

Michael also traced Mary and her family before he turned his attention to tracking down Thomas but, as ever, details were sketchy.

“I started looking for a Cusack in Wales based solely on the note from Michael (‘just returned from visiting my brother in Wales’),” he explained.

“I knew it was either Thomas or Patrick and, eventually, I got a guy in Wales called Thomas, but I lost him in 1891 - I couldn’t find him anything going through census records or anything else I could find.

“I decided to broaden it out and, when I did that, I found him in Wimbledon. In the 1911 census, I got the word that clinched it for me - he said he was from ‘Carron, county Clare’, the townland they grew up in.

“He never married, he worked in the civil service and lived in digs all his life until he died in 1933. Maria and I went over to Wimbledon and found his grave. There probably wouldn’t have been more than three or four people at his funeral and I would be 99.9 per cent certain that no one stood at his grave from the day of his funeral until Maria and I stood there. Nobody knew he was there.”

Three down, one to go. The last of the brothers was Patrick and Michael came up against brick wall after brick wall as he tried to trace him. Eventually, he made the breakthrough and discovered that Patrick had emigrated to the USA in 1870, two years after his father Matthew died.

“Because I’d found Thomas I knew the man I was looking for was Patrick,” said Michael, 76, a lifelong GAA fan who lives in Poyntzpass, county Armagh but remains a fan of his native county Down - his nephew Kevin Anderson played for the county last year.

“I tried the States and I tried New York. There are hundreds of Patrick Cusacks but, after two or three months, I picked up a lead. I went through the various censuses and I found out that he had a son named Matthew. Now Patrick’s father was called Matthew and, at that time, it was customary to name a child after his grandfather.

“He was in the 1900 census, but he wasn’t in the 1910 census - he had died. After a lot of hunting, I found his death certificate, I sent off for it and when it came back it stated that his father was Matthew Cusack and his mother’s name was Bridget Flannery. That sealed it for me and I traced all his children and the only one who has evaded me is his daughter Catherine.

“She was in the census in 1915 but disappeared afterwards and I’ve spent hundreds of hours, but I can’t trace her. She was 31 then and unmarried, so she may have joined an order of nuns or gone to the war and been killed or gone abroad and met somebody from who knows where and settled anywhere. That’s the only one who was beaten me.

“One of the family died in New York in 2012 and I wrote to the undertaker and explained what I was doing and asked him to pass on an email on to the family. He said he would, but I haven’t heard anything since.”

Perhaps that email will be answered one day, but Michael’s work didn’t end there. He also traced Michael Cusack’s eight children - three sons (Michael jnr, John and Francis) and five daughters (Clare, Bríd, Aoife, Íde and Ethel).

Mary and Íde died in infancy and Aoife tragically passed away in October 1890, a month after Cusack’s wife Margaret died from the same disease. Afterwards, the family was split up and the two surviving girls - Clare and Bríd - were sent to England.

“Bríd entered a convent based in Clifford, Yorkshire, but no-one knew what had become of Clare,” said Michael.

“After a long period of time, I eventually traced her to Bradford. I got her death certificate and a girl in a local newspaper office got a death notice that had been inserted by her friends and neighbours - she had worked as a machinist in a raincoat factory.

“I rang the Townhall in Clifford and asked if they knew where the convent was and they told me it was all gone and there was a housing estate on it. No graveyard, nothing. I took a chance and rang the parish priest and he told me ‘they’re buried in our graveyard’. I told him that Bríd would be buried in the graveyard and maybe Clare would be too and he said he’d look it up on a map. A couple of days later, he rang me back and told me Clare was buried in an unmarked grave 15 yards from her sister.

“Later on, I got talking to a priest based in that area, a Father Magilicuddy, and he was interested in the story. I asked if the GAA over there would put up a headstone but, six or eight months later, I got an email from him saying there’d been a headstone erected to Clare Cusack. I asked him ‘who erected it?’ He said ‘a man’. He didn’t want to tell me, but I would guess it was him.”

As Michael says “there’s a hundred wee stories” that he could tell from what he describes as “a labour of love”.

“Sometimes, I did think ‘what in the name of God did I start this for!’ but, really, I enjoyed doing it and it was very satisfying when you made a breakthrough.

“Cusack’s family came from very humble origins, but they were obviously very bright people. They were among the millions who went abroad and the thing that sets them apart is Michael. If he had remained a teacher and died in 1906, nobody would have known anything about them, but it’s the GAA connection that has linked the whole thing.

“They left an indelible mark on Irish life, but none of them have any connection with the GAA because none of them is in Ireland - the Irish connection is gone, the Wales connection is gone…”

Michael has kept the line to Australia open through his valuable work and, who knows, maybe someday an email will pop into his inbox from a John Cusack or a Michael Cusack in New York eager to learn about their famous uncle?

“Is your work finished?” I asked him.

“Yes and no,” Michael replied. Of course, he hopes it’s no.

You can read Michael Anderson’s work at the Croke Park Museum, University College Galway and the Cardinal Ó Fiaich Library in Armagh.

MICHAEL CUSACK

Michael Cusack was born on September 20 1847 in the parish of Carran, county Clare and died in Dublin on November 27 1906 at the age of 59.

He trained to be a teacher and was principal of Lough Cutra national school, Galway between 1866 and 1872, earning a salary of £44. For unknown reasons - maybe love, maybe money - he switched to St Colman’s College, Newry in 1871 and was professor of Maths and English until 1874, when he moved to Blackrock College and then onto Kilkenny and Clongowes Wood.

Cusack married Margaret Imelda Woods from Dromore, county Down in St Colman’s Church, Dromore on June 14 1976 and, in 1879, he set up a successful academy at Gardner Place, Dublin to teach young men who hoped to sit bank, civil service or RIC entrance exams.

According the GAA, Cusack attended the first meeting of the Dublin Hurling Club, formed "for the purpose of taking steps to re-establish the national game of hurling" in 1882. The weekly games of hurling in the Phoenix Park became so popular that, in 1883, Cusack had sufficient numbers to found Cusack’s Academy Hurling Club which, in turn, led to the establishment of the Metropolitan Hurling Club.

On Easter Monday 1884, the Metropolitans played Killiomor in Galway. The game had to be stopped on numerous occasions as the two teams were playing to different rules. It was this clash of styles that convinced Cusack that, not only did the rules of the games need to be standardised, but that a body must be established to govern Irish sports.

He was also a journalist and he used the nationalist press of the day to further his cause for the creation of a body to organise and govern athletics in Ireland. On October 11 1884, an article, written by Cusack, called 'A word about Irish Athletics' appeared in the United Ireland and The Irishman. These articles were supported a week later by a letter from Maurice Davin, one of three Tipperary brothers, who had dominated athletics for over a decade and who gave his full support to the October 11 articles.

A week later, Cusack submitted a signed letter to both papers announcing that a meeting would take place in Hayes’ Commercial Hotel, Thurles on November 1 1884. On this historic date, Cusack convened the first meeting of the ‘Gaelic Athletic Association for the Preservation and Cultivation of National Pastimes’.

Maurice Davin was elected president; Cusack, Wyse-Power and McKay were elected secretaries and it was agreed that Archbishop Croke, Charles Stewart Parnell and Michael Davitt would be asked to become patrons. From that initial, subdued first meeting grew the association we know today.