THERE is one serious flaw with the defensive-based running game which has been slavishly adopted by virtually every team in the country.

It has robbed us of the centre half-forward.

And I don’t know about you, but I have a soft spot for the number11 position. It all started with Damian Barton. Barton was the first truly gifted creative player that I ever witnessed on a football field.

My personal nickname for the Newbridge star was Bartoni. I always thought of him as a continental Gaelic footballer. In many ways, he embodied all the qualities of the quintessential Italian soccer player. He was composed. He had style. There was also a certain swagger.

And like your typical Italian pro, Bartoni could also be utterly, utterly ruthless. For Derry, Damian Barton could be good, and occasionally great. For Newbridge, he was a colossus. Think Eric Cantona in a green jersey.

In the same way as Cantona added a measure of Gallic flair to Old Trafford, Barton brought a similar level of refined technique to the playing fields of Derry. His passing was just on a different stratosphere. No one was remotely in the same league as him. In 1989, he captained and carried Newbridge to a county title.

The recipe was simple and a delight to watch. Barton, the quarter-back, split the defences and Liam Devlin scored the goals.

When I was in first year at St Patrick’s, Maghera and Barton was subbing at our school, I got my one and only coaching lesson from the player I adored to watch. During a game at PE, I tried unsuccessfully to place a kick pass to a corner-forward who was being tightly marked. Barton stopped the game.

First, he pointed to the narrow square of ground where I had been trying to aim a pass. Then, he directed my attention to the huge swathe of grass which was totally unoccupied. The advice has never been forgotten. “Always kick to the space,” he said.

Nowadays, the game is all about running and rushing, tackling and harrying. Barton never slipped out of cruise control. He never seemed to sweat. He made it look effortless.

Years later, I marked him in a tense relegation game in Newbridge. He played and managed at the same time. Picking passes while coolly instructing everyone around him. The tone of his voice never wavered, not even in the dying minutes as Newbridge trailed by two points. He was coolness personified. The game ended in a draw.

Perhaps the main reason I like a good centre half-forward is because a great number 11 is the complete footballer.

There are Allstar corner-forwards who can’t catch a ball above their heads. There are also Allstar defenders who, for good reason, never kick the ball. In contrast, a Rolls Royce centre half-forward has mastery of all the skills. Greg Blaney is the supreme example. Blaney had everything - brains, brawn, passion and panache. He could pass, score, catch and tackle. He had the lot.

The first time I saw him play was on a mucky day in Newcastle. It was a winter League game in the late '80s. Heavy air and heavy ground. It wasn’t the type of day for Blaney to showcase his finesse. That didn’t matter. Unlike a lot of stylists, Blaney wasn’t just a hard ground specialist. He could play in all conditions.

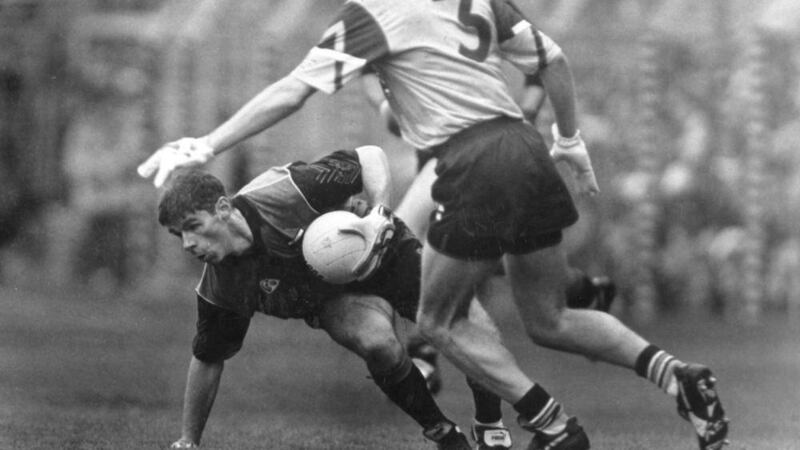

What struck me first about him was his courage. He would dive headlong into a ruck of boots to grab a breaking ball – and he would win it. He was so fearless. Moments after some astounding act of courage, he would dink the daintiest of foot-passes to a corner-forward.

Most Gaelic footballers fall into one of two categories. They are either a soldier or an artist. Few straddle both camps. Greg Blaney was one of the exceptions. On that day in Newcastle, he landed two long range points from about 50 metres. That was the day I joined the Greg Blaney fan club.

The beauty of a great centre half-forward like Greg Blaney was that he unlocked the brilliance of the forwards around him. It’s no coincidence that, when Blaney was in his pomp, Mickey Linden and James McCartan never played better.

Down’s All-Ireland victories of 1991 and 1994 sprung from that magical triangle. With Blaney operating at the point, he sprayed the passes to the left and right wings. It was an exhilarating spectacle.

Yet, think now about the games witnessed in this year’s Championship. In Ulster, I can’t think of one example when a player received the ball on the 40 and created a score with a Barton or Blaney-like pass.

There is a good reason why we have been deprived of this type of play. Teams are no longer playing with an orthodox centre half-forward. The position no longer exists. When teams defend, the entire half-forward line retreats en masse. The preferred option is to run the ball out of defence.

It’s the modern way, but it would be a shame if no accommodation could be made for some of the ingenious footballers that have lit up our lives in recent years. For example, where would the great Maurice Fitzgerald fit into the gameplan which has become the default choice in Ulster?

It would be foolish to suggest that Fitzgerald wouldn’t get his place. But it’s the role he would be expected to perform that might cause a certain amount of anguish.

Rather than allow creative footballers to express themselves, the current trend seems to favour recalibrating them into something entirely different.

Managers would argue that the blanket defence has neutered the effectiveness of a traditional centre half-forward. That’s not entirely true. Armagh enjoyed considerable success last year when they deployed Kevin Dyas as a regular number11.

By holding his position, Dyas provided the Armagh defence with the option of a long ball. Armagh’s ability to turn defence into attack with one kick enabled them to beat the blanket defence as the opposition had no time to get a dozen men behind the ball.

The real problem in football is the herd mentality which affects managers. Too few of them are prepared to think for themselves and try something different.

At its very best, Gaelic football is a celebration of tribalism and talent. We admire our warriors. But the icons of our game are the warriors whose wizardry allows them to rise above and beyond the battle.

Greg Blaney, Maurice Fitzgerald, Ciarán McDonald, Trevor Giles, Brian McGuigan, John McEntee and Colm Cooper. The poet soldiers.

I would love to say that the list goes on. But as things stand, it doesn’t.