SIX foot three inches tall, a mop of blond hair and tattoos which, in the words of former team-mate Martin Murray “left you in no doubt as to his political affiliation”, Kirk Hunter was impossible to miss.

Back straight, chest out, arms held wide, he moved with purpose and, when the red mist descended, oozed menace and aggression.

However, this son of the Shankill Road often strayed well beyond the realms of pantomime villain. At Crusaders, where he played for 13 highly-decorated years, Hunter retains legendary status.

But ask supporters away from Seaview and suddenly the superlatives are exchanged for terms of a much less flattering nature.

After their first ever meeting on the pitch, and one which continued off it with ugly consequences, Joey Cunningham is not exactly chairman of the Kirk Hunter fan club.

It was the opening round of the Irish Cup when Newry Town welcomed Crusaders to the Showgrounds on February 20, 1988. By the middle of the second half, Cunningham was enhancing his already growing reputation, his two goals helping the home side into a comfortable lead.

Never mind complete his hat-trick though, Cunningham wouldn’t even see out the game as he and Hunter – as well as Newry’s Tom Gray and Crues full-back Michael Cash – all saw red following a mid-pitch melee.

“Myself and himself [Hunter] went in for a tackle, he went over the ball, missed me, we ended up on the ground and then there was bodies piled on top of us,” recalls Cunningham.

“At that time I was green as grass, honestly. I didn’t know anything about Crusaders, I hadn’t a clue who Kirk Hunter was – if I had known who he was I would never have taken my eyes off him. Simple as.

“Anyway, Freddie McKnight was refereeing it, he sent Kirk Hunter off first, then Tommy Gray, then he sent me off – for nothing. I didn’t do anything.

“So I headed off down the tunnel with one of the groundsmen, Willie Young. Next thing we’re walking past the Crusaders dressing room when the door opens, and then bang...”

Cunningham smashes his right fist into the palm of his left hand with enough force to suggest that, 30 years on, the psychological wounds remain.

He suffered a fractured cheekbone which kept him on the sidelines for the rest of his debut season. A police investigation followed the incident and Hunter was eventually handed a suspended prison sentence and an IFA ban.

“It was like someone had hit me with a sledgehammer,” explains Cunningham, who was 22 at the time.

“I just didn’t know what had happened - I was gone. I was in so much pain it wasn’t true. I remember actually asking my wife to just let me die to relieve the pain, that’s how bad it was.”

After joining Portadown that summer, he would come up against Hunter and Crusaders on several more occasions through the years.

The Showgrounds, the punch, the police investigation – none of it was ever mentioned. But Cunningham remains convinced that Hunter “made it his business” to be wherever he was on the pitch.

“I’ve never spoken to the man, he never ever said a word to me, but he tried to do me again so many times after it.

“Now I’m not saying I’m a saint, far from it, but he nearly broke my leg at Seaview in one game – the shinguard saved me. It looked for all the world like a bullet hole.

“Another day I made a mug out of him at Shamrock Park. He came thundering behind me ready to break me in half but the crowd gave him away.

“As I got to the ball, I slowed down to let him get close then I flicked it back past him and ran around the other side - he was out on the car track before he realised I had gone the other way.

“The whole crowd just pissed themselves laughing at him. That's how to get even - on the pitch.”

When approached, Kirk Hunter did not wish to comment.

****************************************************

“Ohhhhhhhhhhh Joey Joey... Joey Joey Joey Joey Cunnnnnning-ham”

NO matter how you dress it up, Portadown was hardly a natural fit. A murder hotspot during the Troubles, the town itself was home to some of the north’s most prominent loyalists and contained a National Front element that had been occasionally vocal at Shamrock Park.

Yet, less than two years into the job, Ronnie McFall was in the process of constructing a team that could challenge for major honours. Joey Cunningham would become a crucial part of the jigsaw.

Trusted scout Jackie McCreanor had given glowing reports but it wasn’t until McFall went to the Showgrounds himself that the decision was made.

“I saw him playing for Newry Town and he was absolutely electric, just unbelievable,” recalls the veteran boss, who remained in charge of the Ports until 2016.

“He was going past people for fun and I just remember saying to Jackie ‘we have to sign him’.”

And when Cunningham met McFall at the Seagoe Hotel, any reservations about making the move to mid Ulster were quickly dispelled.

“I tended to go towards people who I felt comfortable with, people who I respected and who I felt respected me. It was never about going to the team who was going to win all the cups, that never bothered me. For me it was about people who appreciated you as a person.

“It’s just funny how things work out.”

Cunningham’s arrival coincided with a glorious era for McFall’s men around the turn of the decade.

Sandy Fraser and Stevie Cowan were soon added to a squad backboned by stalwarts like Mickey Keenan, Brian Strain and Philip Major, the two Scottish imports forming an instant bond up front.

But it was the Crossmaglen man who sprinkled the magic dust up and down the right flank as Portadown won back-to-back titles in 1990 and ’91, completing a memorable double second time around by adding the Irish Cup to the collection.

Some supporters even used to move around to the opposite side of the ground at half-time to make sure they could continue to watch the wing wizard at close quarters.

“Cunningham was one of our best players, no doubt about it,” said McFall.

“He was scoring me over 20 goals a season from a wide right position – you don’t get many wide players nowadays scoring 20 a season.

“When he was still at Newry even, Billy Bingham actually said to me about him ‘Ronnie, he should be playing in England’. He was that good.”

But crossing the pond couldn’t have been further from Joey Cunningham’s mind. He watched on the television as one of his heroes, Liverpool and England star John Barnes, was subjected to horrific racist abuse on a regular basis. And Barnes was far from alone.

Fair play to them, he thought, but it’s not for me.

“I remember Ronnie coming to me a few times about teams wanting me to go over and I told him I wasn’t interested.

“The racism was so bad in England in the ‘80s and I just didn’t want that hassle in my life. To me, the Irish League was probably like an extension of the English League in terms of people’s attitudes... people were ignorant then.

“The English League was all the things I didn’t like, but on a much bigger scale.”

In many ways though, the uniqueness of Cunningham’s situation must have been every bit as trying.

Other black players came and went in the Irish League around this time but none enjoyed, or endured, the kind of profile bestowed upon Cunningham.

“He took a lot of abuse, especially from supporters,” recalls journalist Denis O’Hara, who was on the Irish League beat during this period.

“Some people looked away or nearly pretended they didn’t hear it but Joey could hear it quite well, I could hear it quite well, and I just remember feeling really embarrassed.

“Clubs didn’t seem to do anything about it and the IFA did bugger all about it. The authorities did sweet FA.”

“Joey really handled it well – he would never rise to it,” added Gregg Davidson, the no-nonsense left-back on that Portadown team.

“He had to be physically tough but I would maybe say that mental toughness was one of his main strengths.

“At that time Joey played some great football, and it kind of shut those people up.”

But Cunningham wouldn’t allow himself to be cowed either.

During one game against Linfield at Shamrock Park, a banana landed at his feet as he prepared to take a corner. Rather than kick it to the side Cunningham stripped it, took a couple of bites and threw the rest back where it came from.

“They went f**king mental,” he says with a wide grin.

And while he suffered his fair share of abuse at the likes of Windsor Park, Seaview and Coleraine, Cunningham insists he got plenty “from what people would call my own side of the house” – most notably at Cliftonville and Omagh Town.

As a result, one of the sweetest moments of his career came at Solitude on September 28, 1990.

That Friday night Cunningham scored an absolute screamer, only for it to be scrubbed from the record books when - after celebrating in front of the home fans - a riot broke out and the game had to be abandoned 71 minutes in.

Whether the goal was officially recorded or not is an irrelevance, though. For Cunningham it was all about the moment, those precious few seconds after the ball rippled the net.

“I was getting so much stick, next thing this ball comes out, 30 yards, on the volley, I hit it, left foot, top corner, the whole place just went silent. Aww God boy, it was the best feeling in my life. Just silence.

“I ran over to the main stand where they were all shouting all their sh*t and I stood with my two fingers in the air, just like that,” he says, instinctively rising from his seat to re-enact his movements, “look at me now.”

All of a sudden Cunningham had come full circle; the timid young man who wanted to keep his head below the parapet now found himself centre stage - the unwitting but unashamed firestarter.

“I found my confidence playing with Portadown... instead of worrying about what was being said, it just seemed to draw the best out of me. I loved ramming it into them.

“The Irish League was a horrible place but I was enjoying my football. That Portadown group was tight. There was no bad lads and, I’ll tell you, that’s something.

“They were my best footballing days. I loved it, loved every second of it.”

Yet, long before he had even reached his peak, it was all over.

****************************************************

“THIS is the main family entertainment area... that’s the swimming pools and slides and stuff over there, there’s work going on now to upgrade it... the casino’s through here...”

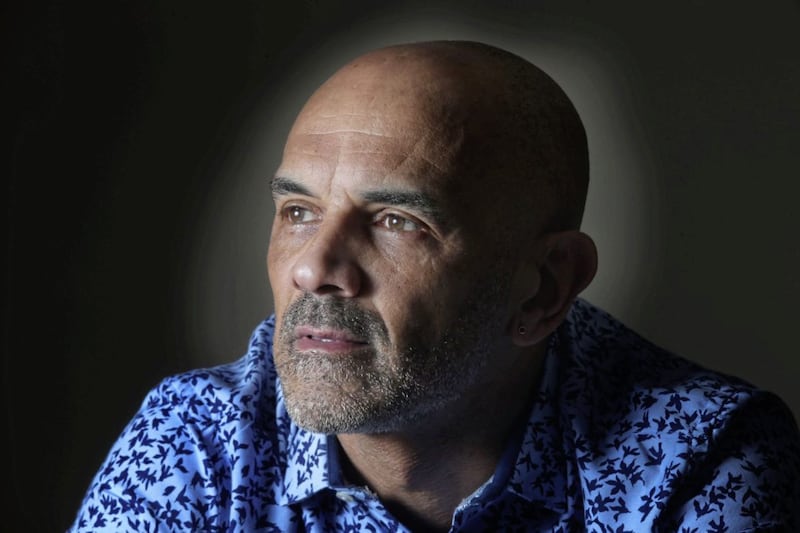

Even at 51 Joey Cunningham still takes a bit of catching up with as he conducts a tour of the Funtasia leisure complex outside Drogheda where he works as a maintenance man.

It is coming up on a quarter of a century since his last competitive kick of a ball, but Cunningham still looks like he has 90 minutes in him.

And as he zooms from one area to the next, there are no signs of the cruciate injury that struck to such devastating effect in 1993.

Countless hours were spent trying to rehab it but Cunningham was floundering in the dark, left frustrated as one attempted comeback after another fell by the wayside.

“There was no follow-up really,” he says, “nobody seemed sure of what to do.”

Three years later, at the age of 29, he was forced to concede the game was up.

Thankfully treatment of cruciate ligament injuries has improved drastically since the early ‘90s. Indeed, much has changed for the better since his day. Unfortunately, though, much has not.

The racist taunts directed at his son Aaron while playing for Crossmaglen against Kilcoo in 2012 marked the darkest day of Cunningham’s sporting journey.

Just over a fortnight ago Liverpool youngster Rhian Brewster revealed he had either personally experienced racial abuse or witnessed it on a football pitch seven times, including five occasions in the previous seven months.

The 17-year-old sought out a journalist from The Guardian to bring the matter into the public domain.

Soccer players like Kevin Prince Boateng, Kevin Constant and Sulley Muntari have all walked from the pitch in the face of racist abuse from opposition supporters in recent years.

When he thinks back to that day at Seaview, looking into the eyes of the father and his young son - or any of the countless occasions he was targeted because of the colour of his skin - part of Joey Cunningham wishes he had done the same.

But still he asks himself the same questions: would it have made any difference? Would anybody have taken any notice?

And the answers, sadly, remain the same.

“If it was nowadays I would have no problem walking off the pitch but back then the Irish League didn’t care. They didn’t give a damn.

“You go out on a pitch and you expect the people who are running the thing to be responsible for minding you to an extent, but they turned a blind eye. They were at the matches, they could hear it. We were in enough finals, you’d all the bigwigs there, but they didn’t care.

“They were happy to live in their world but they didn’t want to know, or care, what was happening in mine.”

As a result, Cunningham spurned opportunities to represent Irish League select sides against high class opposition. When tentative inquiries were made about the possibility of being called into the Northern Ireland squad, they were politely declined.

He has no regrets about the path he chose.

“I didn’t want to play for people who were abusing me - I can say that now.

“I was always brought up to take people as you find them. There was nothing I could’ve done at that time that was going to change it because I was on my own, but thankfully things are changing now.

“I live a lot of my life through my kids these days and just to see them happy and see people respecting them for who they are, that’s what it’s all about.

“That’s the most important thing in life – treat others as you would want to be treated yourself.”