A DRUNK little man on the street. Passers-by turned their noses up as they avoid him, oblivious to who he is, or was. What could he ever have achieved? They thought. What could he have been except what he is? Little did they know…

This is the story of a quiet, talented man who fell on hard times. An Irish international boxer, a Commonwealth Games medallist, a marvellous two-time, two-weight national champion who in his heyday was this island’s most exciting fighter and fiercest puncher. He could have been more than a contender; he could have been a world champion and a household name but his life didn’t work out that way.

This is the story of Johnston Todd.

RAT-A-TAT-TAT. Hard knuckles knock on the door.

“Are you there Johnston?” calls a familiar voice through the letterbox.

A rap on the window.

“Johnston… Are you in there mate?”

Johnston Todd stayed still and quiet until they gave up and let him be. He didn’t want to see his old boxing mates and he didn’t want them seeing him as he pours another glass. Whiskey, the one opponent that even he couldn’t knock out, had him trapped in a corner.

Life outside the ropes was a struggle but in the ring, where fists flew and men tried to hurt him, the man from Ballyclare who stood 5’5” and weighed in around eight stone was a pound-for-pound giant.

Maybe once in a while, as day blurred into restless night and back into day again, his mind drifted off to those boxing days when he won titles in Ireland, across Europe and in the States and fans came from far and wide to watch him fight.

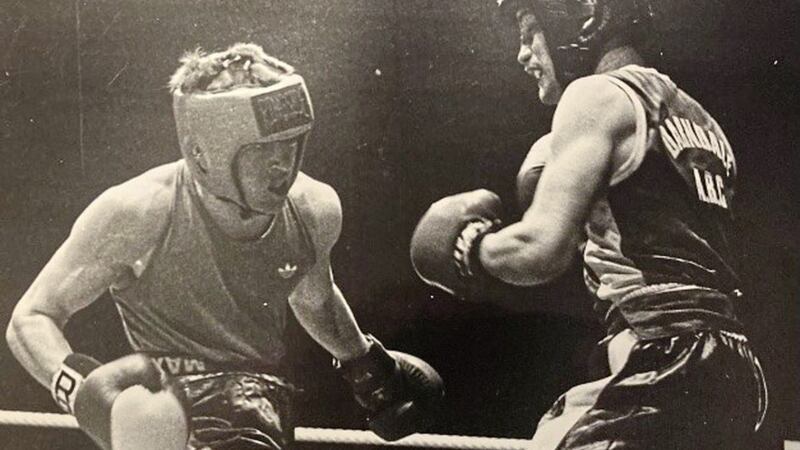

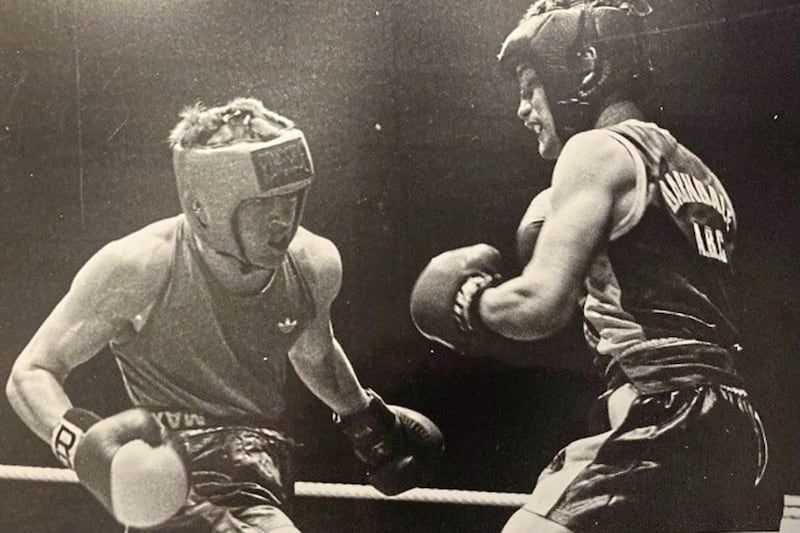

They called him ‘Boom’ because he threw punches that made spectators gasp and opponents see stars and he first got the opportunity to showcase his skills at international level in 1984. Paul McCullagh was part of the same Young Ulster team that boxed Young Wales and the memory of perhaps Todd’s most spectacular KO remains crystal clear.

“He was fighting the Welsh champion (at light-flyweight) and this snobby boy came over to us: ‘Oh yes,’ he says, ‘Todd’s fighting our champion,’” recalls McCullagh, now a respected referee who could punch a bit himself in his welterweight days.

“He was saying the Welsh boy would win. I was only 16 at the time but I says to him: ‘Do you want to put money on it?’

“Did you ever see in Kung Fu movies (or cartoons) when somebody gets hit and they spin round before they fall? Well, Johnston hit the Welsh champion and it was the only time I ever saw that happen in real life. He spun three times – three complete circles - and then fell on the ground. I never saw a punch like it. Johnston was the quietest, most laid-back wee man I ever met. You had to poke him to make sure he was breathing, but what a puncher! He’s a forgotten superstar.”

Ask any coach which of boxing’s raw materials they’d choose for a fighter and – bar dedication - most will go for natural power. Footwork and technique can be taught, fitness, composure and strength can be improved but the split-second timing that turns a night out into ‘lights out’ is God-given.

Todd had the gift here’s another example of how he used it from Paul , this time from an international tournament in Denmark in 1986.

“Johnston beat the number two Frenchman in his semi-final and I never saw a kid take such a beating,” he explains.

“He beat him round the ring and won on points. I always remember the French boy going to Johnston (French accent): ‘You beat numba toooo, now you fight numbaaa waaaan’.

“Johnston hit the number one guy in the first round and he fell forward and his throat caught the bottom rope. That was that.”

Todd’s boxing career is punctuated by such stories and his son, Johnston junior, explained that his dad was introduced to the noble art by his father (also Johnston) who trained his four sons in the family home and “out in the back yard”.

Johnston was smaller than his brothers (Andy, William and Ronnie) but it was soon obvious that he had a talent they lacked and after a series of busted noses and black eyes, his father brought him along to the local club in Ballyclare which was run by his friend Norman Turkington.

Regular training polished up the raw skills of the hammer-handed rough diamond. His first successes came at the County Antrim Championships and it was there that Ireland’s Olympic Games coach and Belfast boxing Guru Gerry Storey spotted him and invited him to the Holy Family ABC gym.

“Talents like Johnston are few and far between,” says Storey, the man who brought through so many champions including Hugh Russell, Sam Storey, Neil Sinclair, Carl Frampton and Paddy Barnes.

“Looking at him, that dead-pan face that he had, you’d have thought butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth but once he hit them…

“I saw him in fights when he nearly delivered the big shot and the other boxer gave him respect after that because they knew that if he landed the next one clean it was all over.

“I know bigger men that he hit and dropped and I’m talking about big men – super-heavyweights. “I’ll mention no names but I remember hearing about him dropping a heavyweight one night. When I heard it I said: ‘What the hell was he doing in with him?’ They were in sparring and Johnston dropped him but that was him he’d have been in there with anybody.

“When he was strong at the weight and he hit them… They were out cold.”

There were Ulster and Irish underage titles to go with his international successes and Todd’s first Irish senior title came in 1986 at light-flyweight when the referee jumped in to stop the contest in round one with opponent Michael Thompson out on his feet. He went to the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh that year and reached the semi-finals at light-fly before losing narrowly to Canada’s future world champion Scotty Olsen.

By 1990, Todd had moved up to bantamweight and he met Joe Lawlor in the final of the Irish Elite Championships. Skilful Lawlor had represented Ireland at the 1988 Olympic Games and was as tough as they came but he was beaten from pillar to post and referee Pat McCrory stopped it in the second round.

“Joe told me he thought the stadium had collapsed in around him,” recalls Storey.

That win was Todd at the peak of his powers. He lost to granite-chinned Wayne McCullagh in the 1991 Ulster final at a packed Ulster Hall and 1992 was his last competitive year as an amateur. The natural next step was to unleash the Ballyclare dynamo into the professional ranks as a destructive bantamweight.

Fight fans would have loved him. He had the amateur pedigree behind him, dynamite in both hands and he’d already served notice that he had the tools in sparring sessions against seasoned pros.

“I remember one time Barney Eastwood told me he needed a sparring partner for a guy they’d brought in to fight Dave Boy McAuley and I said: ‘Ok I’ll go and see Johnston’,” says Gerry Storey.

“He was doing a job delivering fruit but he took the time off and went up to spar. They ended up having to stop it. Barney said: ‘Gerry, for God’s sake don’t be bringing him back or we’ll be looking another opponent for Dave Boy’.”

Storey pulls no punches when asked how far Todd could have gone as a professional prize fighter: “He could certainly have been a world champion,” he says, but due to a combination of lack of opportunity and lack of ambition, Todd never made the switch.

“He would have been a terrific pro,” Storey adds.

“But he wasn’t interested and, at the same time, I wasn’t either. At that time I was interested in keeping lads off the streets and coaching them right and that’s the main thing to do.

“So you never saw the best of him because he would have been a great bantamweight. He would have had problems getting to eight stone but once he got there he would have been unbeatable.

“He would have been in to learn the game right, he would have knuckled down to scheduled training and programmes and the longer rounds would have suited him.”

Johnston junior had arrived in 1990 and becoming a parent at the age of 22 began to change his father’s outlook on life. He was reluctant to leave his family and with mouths to feed, he didn’t have the time to spend perfecting his ‘Suzie Q’ (his right hook) night after night at the Holy Family gym.

Maybe he was glad to walk away because there can be an unseen price to pay for hurting another man. Leaving an opponent unconscious on the canvas didn’t always sit easily with Todd’s sensitive nature and he was haunted by the memory of one knockout win in particular. You wonder whether his punching power was a blessing, or a curse?

“He told me about one night when he hurt someone,” says Johnston junior.

“He knocked the fella out and he said it always stuck with him. The fella was lying unconscious in the ring and my dad never found out if he came round again, he was taken out of the ring on a stretcher.

“He said that always stuck with him, he didn’t like it. He always hoped he was ok but he never heard of him again in boxing. It scared him a bit.”

As time went on the discipline and focus of the boxer’s life gradually ebbed away and after the break-up of his marriage the two-time Irish champion began to lose his battle with alcoholism. Johnston junior, who stayed with his dad when the family split, witnessed his sad decline.

“I used to get a bottle of whiskey and pour it down the sink,” he says.

“Sometimes I would get a phonecall when I was 14 or 15 saying: ‘Your daddy has fell down the street and he’s smashed the back of his head’. I had to go down and fireman-carry him up home - you can’t put sugar on it, that’s the way it was.

“In the end I stopped pouring the drink out because if I did that he would have walked down and got another bottle and maybe fell and hurt himself. You couldn’t win.”

And when his former coach tried to stay in touch, the fighter he had moulded into a fearsome champion remained hidden in the shadows.

“Things didn’t go right for him,” says Gerry Storey.

“We would have taken a race to Ballyclare to see if we could get talking to him and get him interested in life, nevermind anything else, but it ended up he would have been hiding away from us and he didn’t want to see us at all. He didn’t want us to see him.”

A gifted handyman, Todd also worked as a coalman, a roofer and a labourer and loved to spend evenings watching westerns with his father. Sadly cancer took his dad from him in 2010 and he was unable to cope with the loss.

“He just went downhill after that,” says Johnston junior.

“He started drinking worse and going down the gutters. He didn’t really care and he was drinking maybe two bottles of whiskey a night raw and not eating. It got to him in the end.

“At Christmas time in 2011 he gave me money to give to my sisters and presents for them. He gave me a hug and said: ‘Love you, take that to your sisters and I’ll see you when you’re up again’.

“The next morning my granny rang and told me he’d passed away. He was in the same spot I’d left him the night before, sitting in the living room with the TV on and a glass of whiskey on the wee table beside his chair. He passed away in his sleep.”

Johnston Todd was just 43 and the cause of death, officially recorded as liver disease, was alcohol poisoning. His family was told that the thing that kept their father alive for so long was his massive heart.

His son’s biggest regret is that he never got to meet his grandchildren.

“I have two kids now and I would have loved for them to meet him,” he says.

“My two sisters have two kids each as well and they feel the same. I would love to have seen him with the kids. They would have taken him away from the drink and given him something to motivate himself.”

With the right training, management, hard work and a little luck, Johnston Todd could have taken over the mantle of Ireland’s top boxer from Dave Boy McAuley who himself had replaced Barry McGuigan. A rare talent was lost.

“He could have been a world champion but he never took it as seriously as he should have, he just got caught up with the wrong people,” says Johnston junior.

“But I’m proud of what he did and it made him proud telling me about the things he did. He didn’t wish he could turn back time to become more.”

He never saw his dad’s glory days in boxing and many a time he saw him at his worst but he’s always been proud and in his house there’s a room filled with the medals, trophies and certificates left behind by the little fighter with the big heart.

He hopes we remember him, not the lost soul on the street.

Rest in peace Johnston Todd.